A Wisconsin toddler has beaten the odds and is on the path home after spending most of his life in the hospital.

Kingston Vang-Wraggs, 3, was discharged from American Family Children's Hospital in Madison, Wisconsin, part of the UW Health Kids system, after 640 days. While there, Kingston received a kidney transplant and fought off flesh-eating bacterial infections, among other challenges.

Kingston's father, Tommy Wraggs, said his son's ordeal began in September 2020, when he noticed his son, who was born with chronic kidney disease, was experiencing cramps one evening. He first rushed Kingston to their local hospital in Wausau, Wisconsin, but later brought him to American Family Children's for additional care.

Dr. Neil Paloian, one of Kingston's doctors and a pediatric nephrologist, saw Kingston that first night.

"His whole body was puffy and he had a bunch of labs that were very abnormal," Paloian told "Good Morning America."

Paloian said he knew Kingston had a type of kidney disorder called nephrotic syndrome but it wasn't until later, after genetic testing, that he and Kingston's care team determined he had congenital nephrotic syndrome, a rare variant that instead of being caused by an infection or medicine, is a condition a child is born with, according to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

"Congenital nephrotic syndrome is actually quite uncommon, even for rare diseases. Since I've been here at UW -- in the seven years -- [Kingston] has been the only case we've diagnosed," Paloian said.

With congenital nephrotic syndrome, Paloian said "[the kidneys'] filter actually gets damaged and the kidney gets damaged, and we know that these children will end up going into kidney failure."

"As soon as we made that diagnosis, we knew that he would eventually get a kidney transplant," he continued, adding that there is no cure for congenital nephrotic syndrome.

But at the time of his diagnosis, Kingston was too small for a transplant and was being fed through a gastrostomy or G-tube. He also took a turn for the worse when he developed a flesh-eating bacterial infection in his G-tube area, the issue that brought him to American Family Children's in the first place.

He would end up having to stay in the hospital's pediatric intensive care unit, or PICU, for months. Doctors told Wraggs his son might not make it several times and, at one point, Wraggs told "GMA" he was even asked to sign a "do not resuscitate" order for his son.

"I refused," Wraggs said. "The way I saw it is, if [Kingston's] willing to fight, I should be willing to fight and I'm his voice. He fought his way through it. How? None of us understand. But he's here."

Once Kingston overcame his infections in the PICU, the next hurdle for his doctors and nurses was to make sure he was healthy and big enough for a transplant. Wraggs remembers the day he got the call letting him know Kingston had been matched.

"I remember being in a locker room at the gym, trying to get dressed and trying not to cry in front of other guys in the locker room," Wraggs said. "I don't think I've ever cried from being happy. So it was pretty amazing."

Kingston received his kidney last month and has been making progress each day.

"To our surprise, it actually was the smoothest thing about Kingston's entire medical course -- the transplant, which is a very complicated surgery," Paloian said. "It's a very difficult recovery, and it's difficult managing a transplant patient but Kingston, so far -- he's done great."

"He just had one complication after the next and he was in the hospital for so long," he added. "It's such a miracle that we were finally able to get him home."

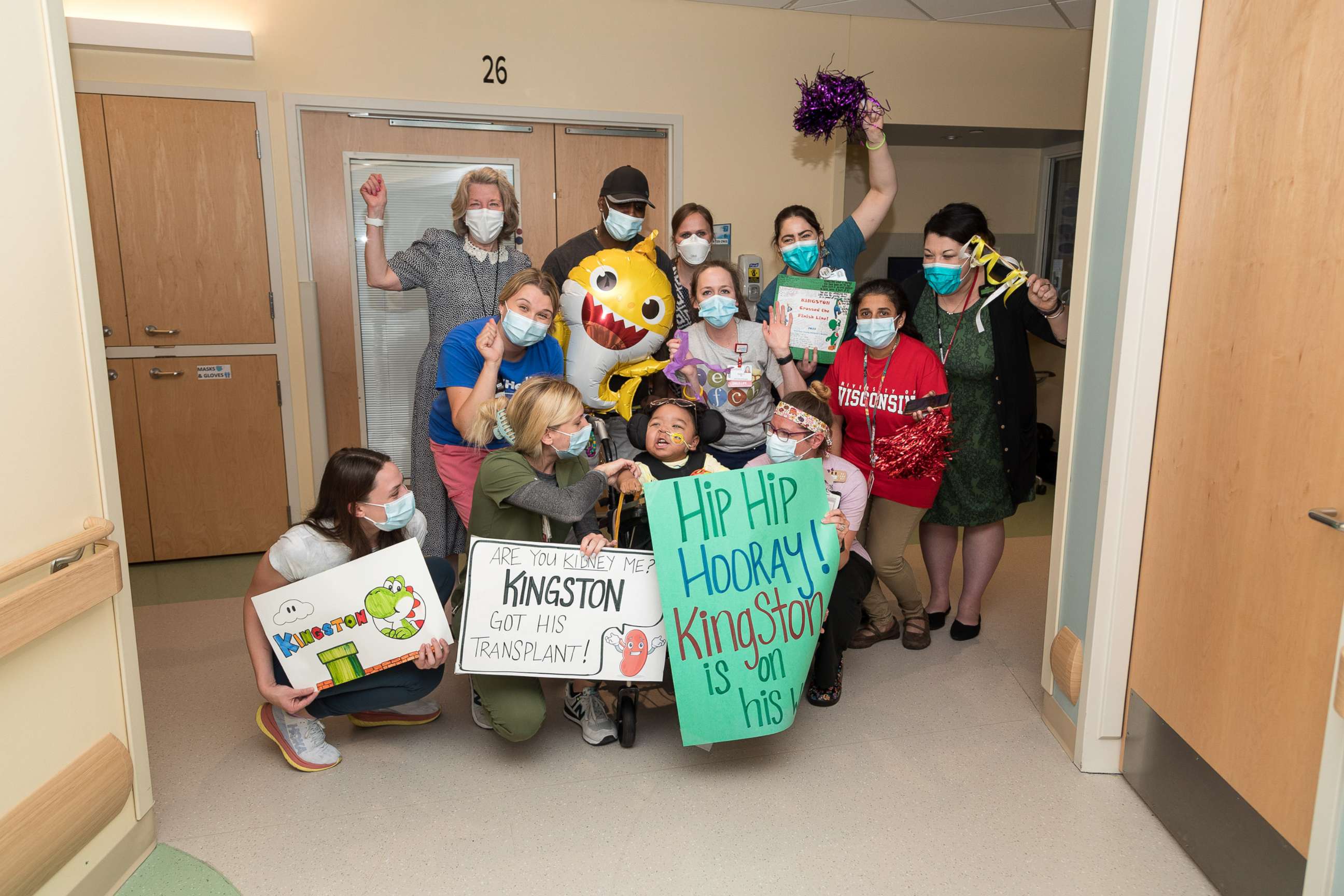

Throughout his nearly two-year hospital stay, Kingston was cared for by dozens of doctors, nurses and staff, some of whom were able to give him the biggest send-off parade on June 29, complete with bubbles, balloons and colorful posters, when he was well enough to be discharged.

"There's not a person in this hospital that this kid didn't touch a part of their life," Wraggs said. "He was never just a patient to them. They say it takes a village. This one here, he's proof."

Wraggs said his son has, without a doubt, changed his life.

"Kingston made me the best person I could be. He saved me. I had a great job, a good career and everything but I don't really think I started living and enjoying life until I went through this journey with him," Wraggs said, adding that he stopped doing financing for car dealerships in order to take care of Kingston.

Today, Kingston and his dad are out of the hospital and staying at the Ronald McDonald House for a couple of weeks until they can go back home together.

"He's doing great. He's very curious. When he sees people, he tries to speak to them. He's learning to love outside when it's not too hot. Soon as the wind hits his hair, he's happy," Wraggs said.

Looking back, Paloian said he's learned a lot from Kingston's journey.

"There's a reason why we don't give up on kids. We know how strong they are and we know how resilient they are, and I think Kingston is the prototype example of that," he said.

"The other thing that I've learned taking care of Kingston throughout all of this, is that we always know that in medicine, we don't practice in isolation, that we have a team and that we are a team, but Kingston's case, more than ever, reiterates what teamwork really means," Paloian added.