Texas law restricting access to abortion pills goes into effect: What to know

As the U.S. Supreme Court continues to weigh whether to leave Texas's unprecedented six-week abortion ban, SB8, in place, a new law that also restricts abortion access is going into effect in the state.

Starting Thursday, people in Texas will have a narrower window in which they can receive abortion-inducing medication, including the two most commonly used medications, mifepristone and misoprostol.

Senate Bill 4, or SB4, cuts the window in which physicians are allowed to give the medication from 10 weeks of pregnancy to seven weeks.

The new law also prohibits mailing abortion-inducing drugs, a restriction that contrasts with a federal regulation enacted in April by the Biden administration that temporarily allows the medication to be mailed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Current Texas law already bans providers from administering medication abortion using telemedicine, according to Abigail R.A. Aiken, MD, MPH, PhD, associate professor of public affairs at the University of Texas at Austin and principal investigator with Project SANA, a research project focused on self-managed abortion in the U.S.

"We've seen many states be able to open up new models of care where clinic-based providers can now do medication abortion by telemedicine," said Aiken. "I think Texas is very clear that they don't want providers here to follow suit and be able to start doing those kinds of new models where you would do a phone consultation with a provider and then have the pills mailed to your house for use at home."

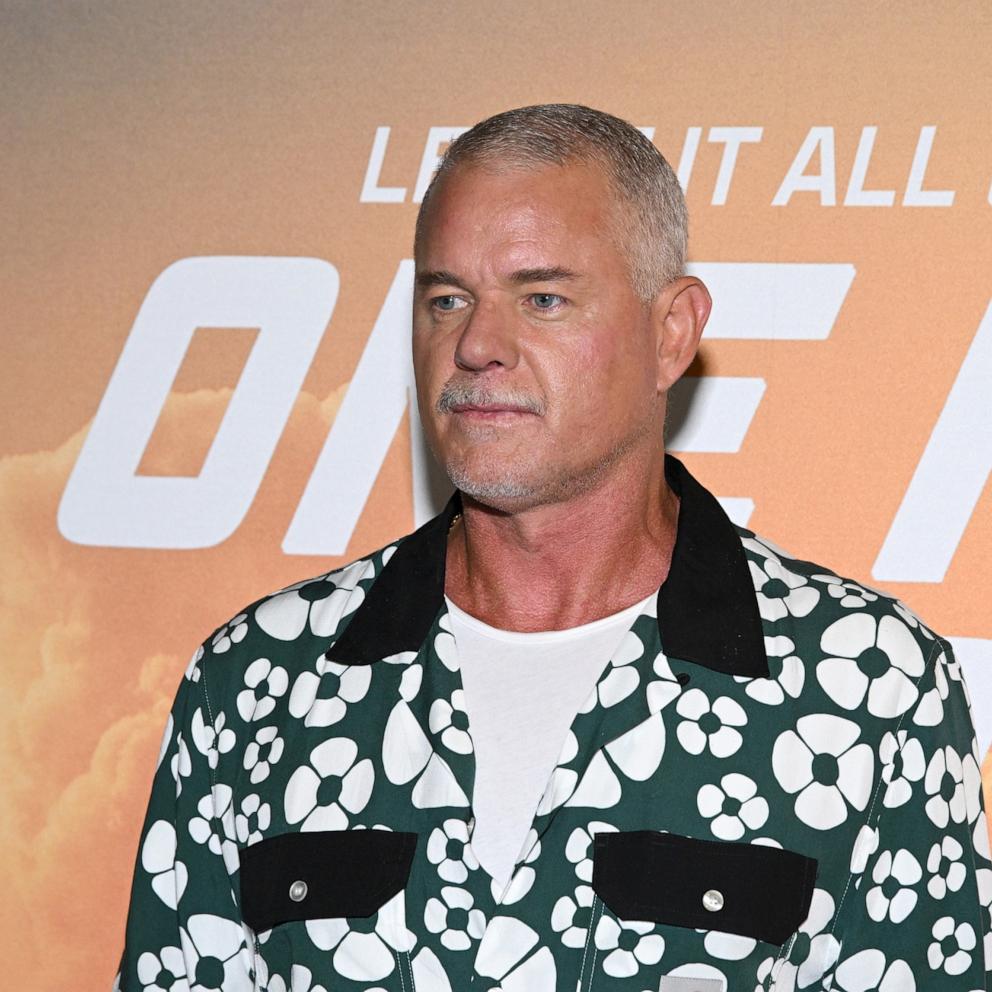

The bill, signed into law by Gov. Greg Abbott on Sept. 24, also adds new requirements around medication abortions, including an in-person examination by a physician, a mandatory follow-up visit within 14 days and new reporting requirements for providers.

The bill also creates a state jail felony offense for "a person who intentionally, knowingly, or recklessly violates provisions relating to abortion-inducing drugs," but exempts pregnant people on whom a medication abortion is "attempted, induced or performed," according to the bill summary.

Though SB4 is being enacted in Texas, medication abortion is now a very common method used for abortions in the first 10 weeks of pregnancy. In 2019, 42% of all abortions in the U.S. were early medical abortions, meaning medications were taken at nine weeks or earlier after conception, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Medication abortions were first approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2000. FDA guidelines advise that abortion-inducing pills are safe to use up to 70 days, or 10 weeks, after conception, though evidence shows it can be safe even later in pregnancy, according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

In most cases in a medication abortion, mifepristone is taken first to stop the pregnancy from growing. Then, a second pill, misoprostol, is then taken to empty the uterus.

Of the two medications, mifepristone is more restricted by the FDA. Since 2011, the agency has applied a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy to mifepristone, preventing it from being distributed at pharmacies or delivered by mail like other prescription drugs.

It must be ordered, prescribed and dispensed by a health care provider who meets certain qualifications, and may only be distributed in clinics, medical offices, and hospitals by a certified health care provider, according to FDA guidelines.

The FDA's rules, combined with state restrictions like the one in Texas, have the effect of not only limiting when, where and how people can get abortions, but also potentially misguiding people on the safety of medication abortion, according to Dr. Bhavik Kumar, a staff physician at Planned Parenthood Center for Choice in Houston.

"What's important to note is that the medication used in medication abortion has been used in this country for 21 years and it is extremely safe," said Kumar. "We've learned a lot since it was first introduced and can use it in different ways that are more patient-centered, more evidence-informed and really optimizes science and medicine so that patients get the care that they need."

Speaking of the new law now in effect in Texas, he added, "What Senate Bill 4 is doing is inserting itself squarely into my relationship with my patients and telling me how to practice medicine, and it's not in the best interest of my patients. It's actually causing more harm to my patients and it's taking options away from them."

Abortion rights advocates say SB4 also has the likelihood of signaling to other states that further restrictions on medication abortion can be put in place.

In South Dakota in September -- the same month SB4 was signed into law in Texas -- Gov. Kristi Noem, a Republican, issued an executive order directing the state's Department of Health to establish rules requiring that abortion-inducing drugs only be prescribed and dispensed by a state-licensed physician after an in-person examination. Noem said she also plans to pass legislation next year that makes "these and other protocols permanent."

Across the country, more than 30 states require clinicians who administer medication abortion to be physicians, while 19 states require the clinician providing a medication abortion to be physically present when the medication is administered, according to the Guttmacher Institute.

"I think we have to see this is another continuation of the trajectory of trying to really make abortion a right on paper only in the United States," said Aiken. "It's another way of placing barriers in the way of people."

She continued, speaking of restrictive abortion laws in some states, "I think what it's doing in reality is creating this really uneven picture where you have some states that are moving in the direction of more and more and more accessible care, but the reality in other states is completely the reverse, so we're looking at that uneven picture where your access really depends on your zip code."

Both Aiken and Kumar mentioned the affect laws like SB4 in Texas have on the most vulnerable populations.

Around 75% of abortion patients are low-income residents, and nearly 60% of U.S. women of reproductive age live in states where access to abortion is restricted, according to the Guttmacher Institute, a reproductive rights organization.

"It has been the case in Texas now for decades that we have seen low-income people and communities of color just bear this disproportionate brunt of negative impacts of these laws," said Aiken. "So this is an equity issue and it's a justice issue as well as a health care issue."