How much is too much? Test could show the effect of gaming on your kid’s brain.

Cash, a 10-year-old boy who lives in Los Angeles, is obsessed with the game Fortnite, his mother Rusti says.

Fortnite represents the current pinnacle of game theory and player engagement. It's filled with bloodless violence, intensity and it's peppered with random surprises.

It's constantly being updated with pop-culture add-ons and it's filled with silly victory dances that delight the player. Because it can be played on a console, a tablet or a phone, it can travel with a player anywhere they get cellular data or Wi-Fi.

It is one of the first totally social, play-everywhere video games, with 250 million players. Its creator, Epic Games, is reportedly valued at $15 billion.

Makings of a habit

"He asks me to wake him up 20 minutes early on school days so he can play," Rusti says of her son, Cash. "He doesn't want playdates at other kids' houses anymore … he just wants to be in the house so he can play."

Cash plays with friends from school, his cousins in Costa Rica and random strangers, and is allocated an hour of playing each school night. Rusti doesn't limit him on the weekends, and estimates he plays four to five hours each Saturday and Sunday.

Watching Cash play Fortnite on his iPad can be dizzying as he manipulates the weapons in his arsenal. He has colorful adornments on his various avatars and when asked how he earned those skins, he says his allowance is now paid to him weekly in V-Bucks, the currency used to buy items in "Fortnite."

Rusti confirms that Cash has spent close to $2,000 in the game. "I can get him to do any chore I want if I pay him in Fortnite money," she says.

Is there is anything he'd rather be doing than playing Fortnite?

"That's a good question … but ... no!" he says.

His mom says he often screams with joy at events in the game and Cash admits he "rages."

"When someone kills you or you die of fall damage and you get angry at that, and you just go insane on your tablet and you throw it," he says. He admits there are times when he forgets to eat and times when his body tells him he's played too much.

"When you're just lightheaded and you can't get enough 'Fortnite,' but it hurts inside," he says.

Effects on the brain

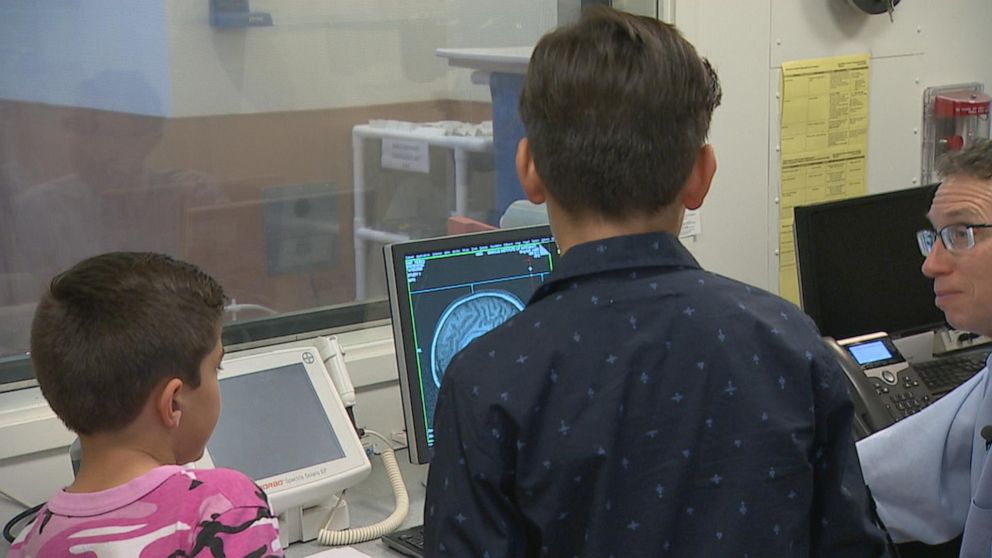

Andrew Newberg, M.D., a neuroscientist at the Marcus Institute of Integrative Medicine at Jefferson Health, has devised a way to illustrate some of the physiological and structural changes happening to gamers. He wants to compare a gamer's brain to a non-gamer's brain to see how the response to different stimuli affects them. Amado, a 12-year-old fellow student at Cash's school who loves music, basketball and watching movies, fits the profile of a non-gamer, occasionally playing car-racing games but who overall isn't into video games.

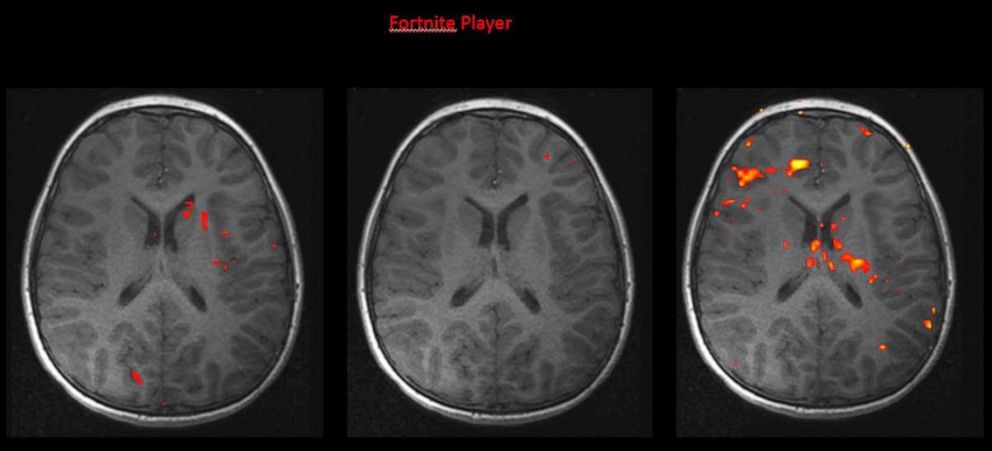

For the experiment, Cash settled into an MRI machine while game footage was played in a monitor bolted above his face. First a control: Newberg contrasts a minute of non-Fortnite gaming video (from an older shooting game that doesn't have the neon colors, social integration or fun dances) with a minute of neutral video (birds at sunset). The neutral video is colorful and moving, so it will stimulate some of the visual regions of the brain. By playing video the older game on the monitor, Cash will see violence, action and many of the same stimuli that he sees in "Fortnite," it just won't be his favorite game. After 10 minutes, Newberg stops the imaging and gives Cash a chance to move his arms and legs. Now for the Fortnite portion: To most accurately simulate the experience of playing the game, video was recorded from Cash's iPad of his actual gameplay, complete with his avatar and favorite skins.

Within a few minutes, Newberg sees the pleasure centers of Cash's brain light up. The presumption is that dopamine is firing into his frontal lobes. After 30 minutes Cash is done.

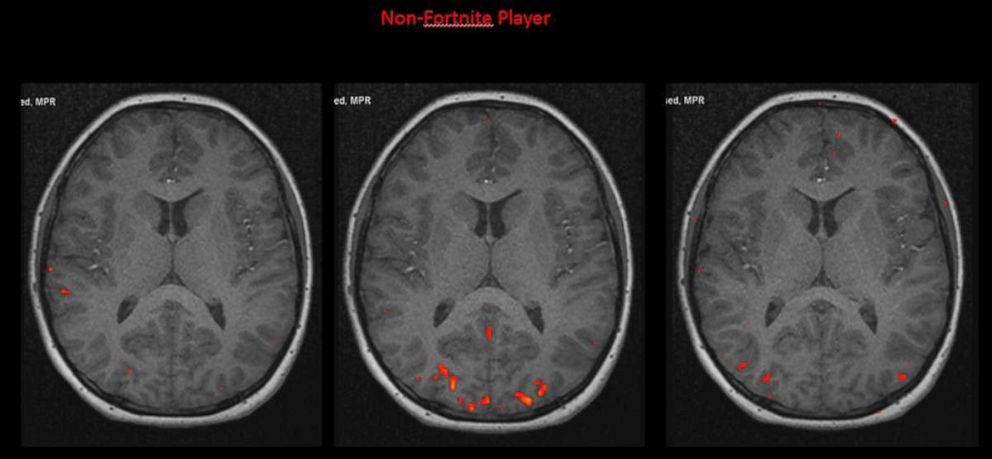

Amado goes through the exact same process. When Amado is done, Newberg analyzes the scans and meets with Cash's mom, who wants to know what's going on in Cash's brain when he's playing the game.

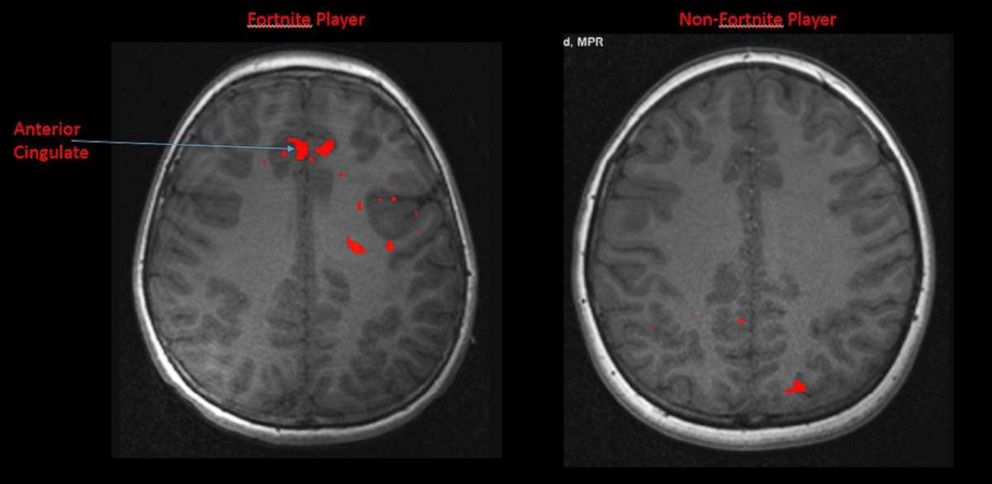

Newberg brings up an image contrasting both boys' brains, and points to the one on the left that has big red and orange blooms of color that Newberg says represent blood flow and stimulation. Cash's brain had much greater activation than Amado's in an area called the anterior cingulate cortex, a structure that can be involved in focus, emotional regulation and addiction.

"These are areas that are very involved in our reward system of the brain," he explains, noting game play delivers dopamine hits to the brain's reward center.

Newberg explains that brain scans of people with internet gaming disorder, an addiction classified in the "Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders," show these rewards centers are enlarged. It takes more and more dopamine for people with this problematic gaming behavior to experience the same levels of euphoria.

The data on gaming and addiction varies widely: a meta study done by Mass General in 2017 examined 116 different gaming studies summarized their findings with the reality that there's a lot we still don't know.

"We are still working out what aspects of games affect which brain regions and how. It's likely that video games have both positive (on attention, visual and motor skills) and negative aspects (risk of addiction), and it is essential we embrace this complexity," says a report in "Frontiers in Human Neuroscience."

"I think everything in moderation … I don't know what moderation is with Fortnite."

The reward centers of the brain in people with internet gaming disorder look different than those of non-gamers. They are smaller. In layman's terms, the physical structures that signal happiness or satisfaction to the brain are robust compared to people without the disorder. One possible theory for that difference is that gaming produces so much dopamine on such regular intervals, that the part of the brain that makes us happy about little things, gets lazy or out of shape. To quote another study published in "Substance Abuse & Misuse" on "reward deficiency theory," "the modified reward system leads to lower enjoyment from the same level of rewards that excited a person in the past, and hence propels people to seek additional rewards; in this case, possibly also from substance use." This physical change is consistent across studies that look at other addictions specifically alcohol and drugs.

Despite all this data, Newberg's exercise comparing the brain scans of a gamer and a non-gamer is only an illustration of how the brain's dopamine centers are is being stimulated. And, he clearly states, this is in no way predictive of Cash's future.

"Just because we see a dopamine area lighting up in the gamer that we saw today, that doesn't inherently mean that the person has an addiction," he says. "What it means is that it's affecting the areas of the brain that are involved in that. We ultimately have to find out how they're doing as a person."

Newberg goes on to reiterate that these images are in no way predictive of any addictions, but may help explain Cash's resistance to putting his iPad down and going out to play in the park. He also points out something obvious: addictive disorders are not diagnosed by brain scans but by obsessive and destructive behavior, which Cash is not exhibiting. By all accounts he is a well-adjusted kid with good grades and healthy family relationships.

What now?

How does all this make Rusti want to alter or adjust Cash's playing?

"[It's] a long time for that brain to be doing that," she says. "I think everything in moderation … I don't know what moderation is with Fortnite."

"I know it's gotten to be too much lately," she adds. "Even if I just break it up on the weekends and don't let him go for four or five hours at a time."

If only Fortnite makes Cash this happy, what else is there for him? Where does he go from here? What other joys is he going to seek? And will they compare?

Rusti hopes so, but she knows the change will be hard.