Survivors and activists speak out 40 years after discovery of AIDS

On Valentine's Day 1982, Dab Garner was diagnosed with HIV/AIDS in San Francisco. He was 19.

As the U.S. reaches its 40-year milestone since the discovery of the virus, survivors like Garner are taking time to reflect on the lives and the stigma carried by those who remain. Garner and about 75 million others worldwide have been affected by HIV/AIDS.

"You have to remember, during this time period there were no laws protecting people with HIV. So someone could be fired from their job, kicked out of their place of residence and be on the street within 24 hours of people finding out they were positive," Garner explained.

Garner, who was married to his partner, Brad, in 1985 adopted an infant named Candace who also had been diagnosed with HIV/AIDS.

"In August of '89 she had to go into the hospital, and we were both holding her when she took her last breath. That was probably the worst day of my life," Garner said.

Just four months later, Garner also lost Brad to the virus.

"My partner became extremely ill and was running a 104-degree temperature," Garner recalled. "We rushed him to the hospital. I had no idea that once they took him back, I would never see them again."

Seven months later, Garner was hospitalized for the virus but survived.

In an effort to help cope with his survivors' guilt, losing both his partner and his child so quickly, he founded Dab the AIDS BEAR Project, a community based organization of citizens affected and effected by HIV/AIDS.

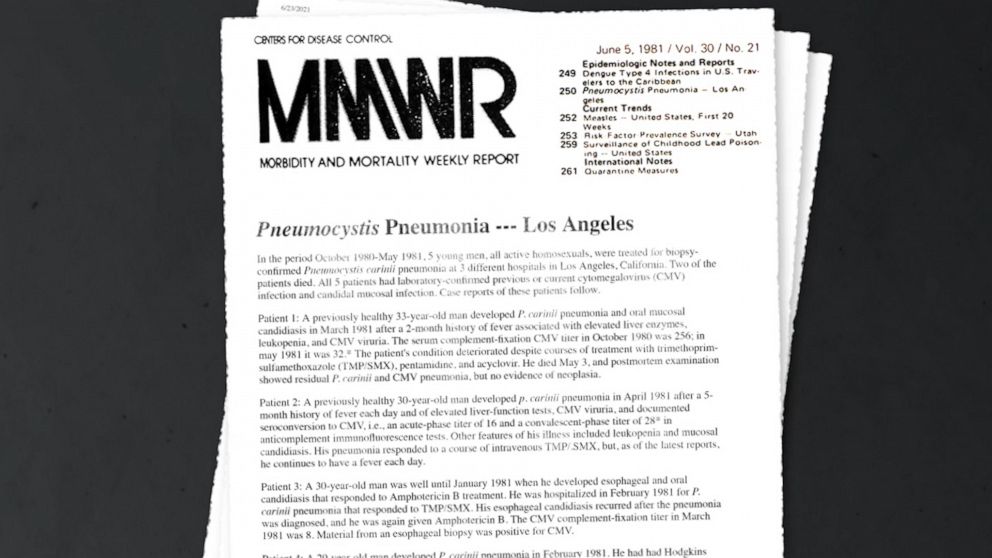

Researchers such as Dr. Anthony Fauci, who gained popularity during the COVID-19 pandemic, and Dr. Monica Gandhi have studied the virus for nearly four decades. Both recalled early detections of the virus -- five homosexual men in Los Angeles were showing pneumonia-like symptoms, Fauci recalled.

"It was at that point, 40 years ago, where I can tell you chills went up and down my spine," Fauci told ABC News, "because, being an infectious disease person, I said, 'Oh, my goodness, this has to be a brand new infection.'"

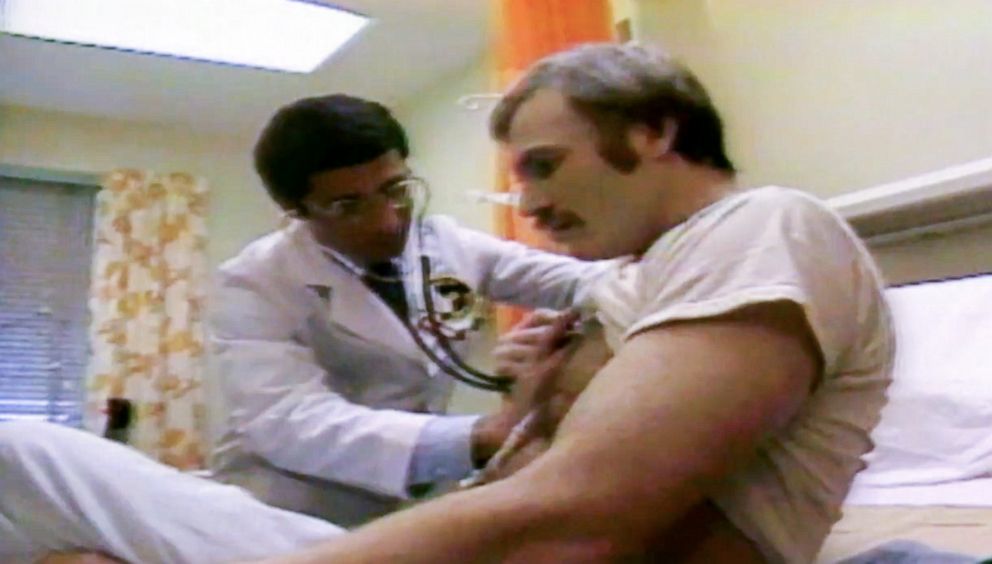

Fauci also remembered the tumultuous challenges when most of the patients began dying from seemingly unknown causes within just days of each other.

"One of the things that became very clear is that when you're dealing with a brand new outbreak and evolving pandemic, that you learn things in real time," Fauci said. "It was just literally a matter of several months, as you saw, injection drug users, hemophiliacs, recipients of blood transfusions, the female sexual partners of men who had this disease, and then, finally, children born of women, who were likely infected."

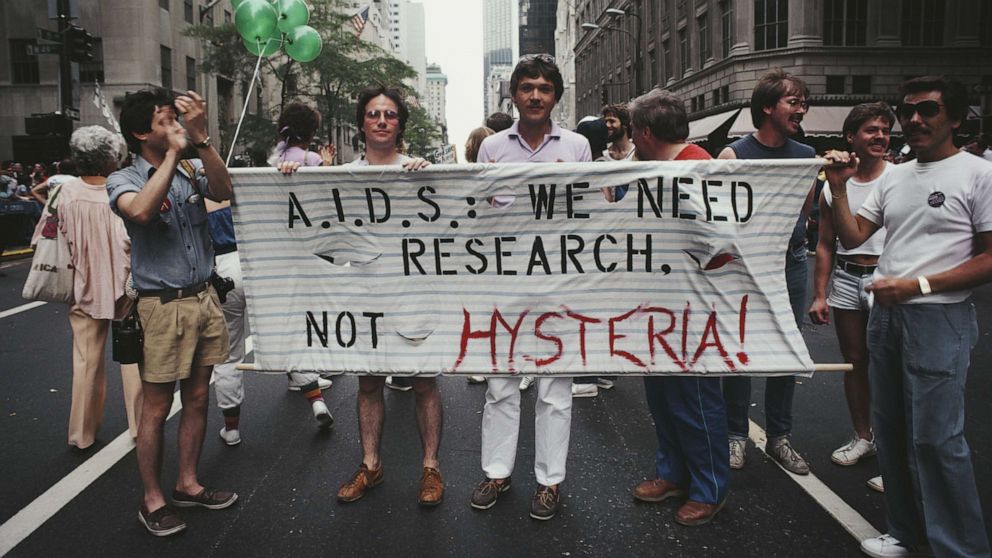

The virus, Fauci noted, still was labeled as a "gay male immune deficiency."

Even as more people who've contracted HIV/AIDS continue living, and living longer, experts and activists say the stigma attached to the virus remains. As with many health-related issues, it disproportionately affects communities of color and the LGBTQ community.

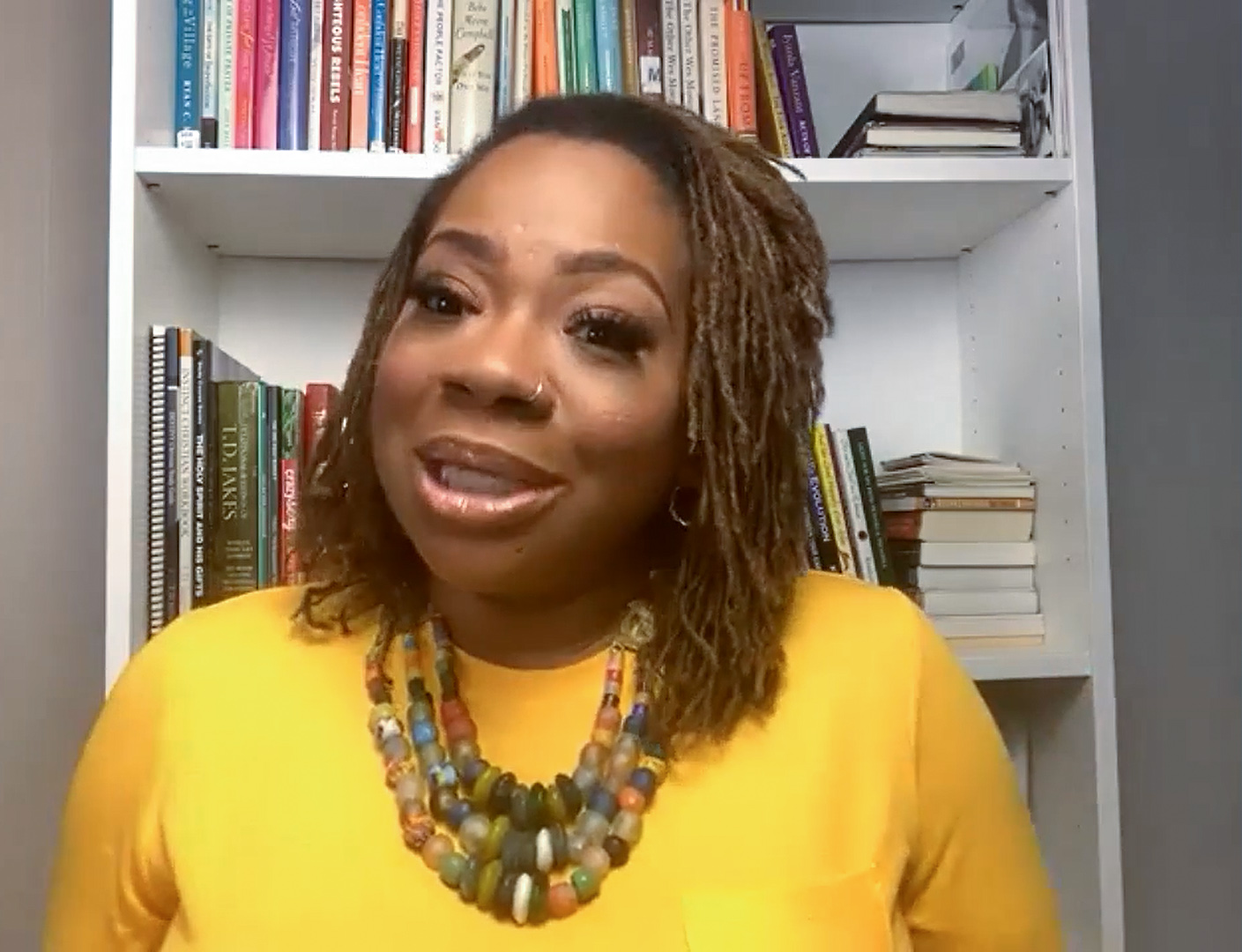

LaDeia Joyce, a Black woman from the South, remembers the moment she received the life-threatening diagnosis in 2016 after contracting the disease from a previous male partner.

"I'm HIV positive. Now, what? Like, that was a phrase I kept on googling and everything I got was very white, very male and very gay," she said.

Joyce said she felt ostracized and polarized, especially as a "Black, cisgendered, heterosexual woman diagnosed with HIV? In the Bible belt?"

That's why she became an activist, to help others with HIV/AIDS.

"It's always a moral Olympics when it comes to Black women and HIV -- it's almost as if we did something to warrant getting this diagnosis," she added.

The virus, which at first mostly only affected gay while males, now afflicts African Americans at some of the highest rates -- while only 13% of the U.S. population, they account for 42% of all new diagnoses, according to a 2018 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"When there is discrimination, when there is stigma, it is harder to access services, harder to go to a medical center and say, 'I need prevention services,'" Gandhi, an expert on the virus, told ABC News.

"It's more difficult for you to come out with your family about your sexual orientation, for your family to help support you access services," she added. "Discrimination and susceptibility to a pathogen have always gone hand in hand."

Now, as an advocate, Joyce is doing all she can to break down the stereotypes and myths surrounding the virus.

"The connection to care, the myths, the stereotypes and stigma, the cost of the medication ... the same things that they probably were dealing with in the '80s, especially when it comes to minority communities, we're still dealing with," she said.

Experts, including researchers like Fauci and Gandhi, said they worry that due to the recent attention focused on COVID-19 some of the momentum to get tested for HIV/AIDS could potentially dwindle.

"What really hit me on the 40-year milestone is that though HIV progress has seemed very quick, in at least over the 40-year span, what we did with COVID-19 -- in a space of just seven months, develop highly effective COVID-19 vaccines -- to me means that HIV is still a stigmatized condition," Gandhi said. "The rapid progress with COVID-19 needs to be translated into better work on an HIV vaccine."