In South Brooklyn, volunteers step in to help low-income residents struggling during pandemic

Whitney Hu knows the route by heart. Every Saturday morning, the 29-year-old wakes up at 6 o'clock to go to a theater-turned-warehouse in the heavily immigrant neighborhood of Sunset Park, Brooklyn, in New York City. There, she slips into the routine she has been performing since the start of New York state's coronavirus lockdown in mid-March.

On this particular day, Hu, the head of South Brooklyn Mutual Aid, a local food relief group in the borough, is joined by Shahana Hanif, another 29-year-old spearheading an emergency food program of her own with her younger sister Sabia, 28.

Hu and Shahana proceed to assemble 403 boxes, each of which are filled with enough food to feed a family of five.

This week's menu of free goods includes pasta, rice, bananas, lemons, apples, tomatoes, broccoli, eggs, bread and vegetable oil. Boxes are also customized to include baby diapers, food tailored to specific cultures, and additional resources if they are delivered to larger families.

"The only help we can't provide are rent assistance and COVID-19 funeral assistance," said Hu. "Those are tougher conversations to have, and for now we could only cover their need for food."

The pandemic has thrust the country into a new normal of survival for some. Hu and the Hanif sisters are just three young leaders taking a stand because they say the government is not doing enough to help their most vulnerable neighbors: low-income immigrants and especially the undocumented community, who are not eligible for bare necessities like food stamps and stimulus checks because they either don't file taxes or they don't have Social Security numbers.

California, whose more than 2 million undocumented residents are the most in any state, is currently the only state in the country to offer coronavirus-related financial support for undocumented immigrants, allocating $75 million to the program. Applications for the funding are approved on a first-come, first-served basis.

"The coronavirus outbreak has revealed so many underlying problems and just how much our undocumented community are suffering," said Sabia, who with Shahana has crowd-raised more than $34,000 to support undocumented Bangladeshis in their hometown of Kensington, Brooklyn, also known as "Little Bangladesh."

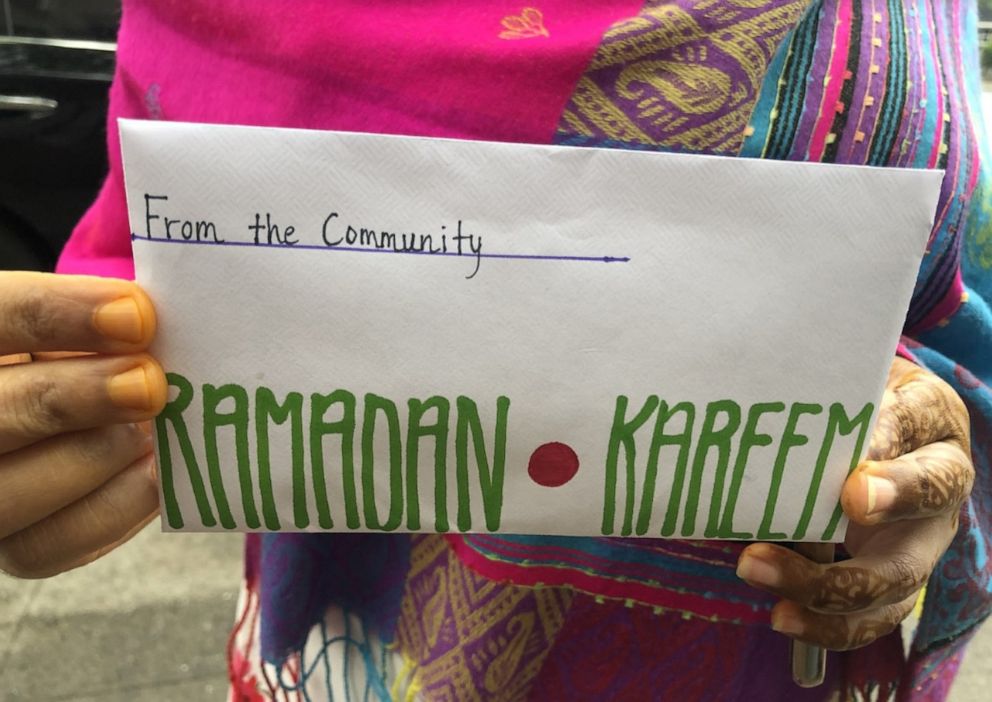

The sisters initially started their campaign to help feed the undocumented for the holy month of Ramadan, which ended on Saturday. But they plan to keep going with their operation. To date, the sisters have given 50 neighbors each a $500 grant, along with halal-friendly food.

"These individuals are our construction workers, our grocery store workers, our domestic care workers," said Shahana, adding that the $500 is not enough but that it's a start. "Everyone who can and who is able-bodied is responsible to do something to make sure we can through this together."

"This is also an opportunity for us to give back as a Muslim," added Sabia, referencing "Zakat," one of the five pillars of Islam that centers around donating a portion of one's wealth to help those in need.

The sisters, along with their parents and several of their friends, have given up their stimulus checks to give back to their neighbors.

Approximately 504,000 people in New York City are undocumented, according to a 2019 report by the Mayor's Office of Immigrant Affairs. Last Monday the NYC Health Department released the coronavirus death rate broken down by zip code, and Kensington had 321 COVID-19 deaths so far. Sunset Park had 191.

"We sprung into action not out of a desire to save but out of necessity for our community to stay safe," said Hu of South Brooklyn Mutual Aid, which has, up to now, fed more than 2,000 families.

In addition to making occasional runs to mom-and-pop stores and accepting outside donations, Hu works with wholesale food providers to purchase goods with the money raised by her aid group, which has reached more than $23,000 of its $50,000 goal.

Volunteers, some who are furloughed or laid off, then assist Hu throughout the week. The effort culminates in a mass distribution day each Saturday, where 30-40 vehicles pick up the boxes of food to hand out to families.

"It's safer to have the drivers pick up the goods than have 400 families line up outside," said Hu, adding that they want to limit any possible exposure to COVID-19.

Every week for the past month, the boxes have gone to 20-30 families of children attending an elementary school in Sunset Park.

Claudia Lechuga, 40, is a member of the school leadership team and the Parent Teacher Association at P.S. 516, a "Title I" school that educates some of the country's largest concentrations of low-income students.

"South Brooklyn Mutual Aid has stepped in to provide a lifeline to our community," said Lechuga, who, along with school administrators, has made wellness calls to the families of all the school's students during the pandemic. "But it shouldn't have come to this. It should have come from a structured government role to help all our neighbors."

Some of the biggest fears Lechuga has heard from families are concerns that they won't have enough food and money to pay for rent. But for the time being, Lechuga said, those in need can count on grassroots leadership to help them get through these trying times.

"We are seeing a ripple effect of young people rising up," said Shahana. "My sister and I didn't create a campaign to seek out undocumented people. We knew there were already a large number of people who were going to be affected by the coronavirus."