Can recovered coronavirus patients help combat the disease?

Can the blood of a recovered coronavirus patient help high-risk cases fight off the virus?

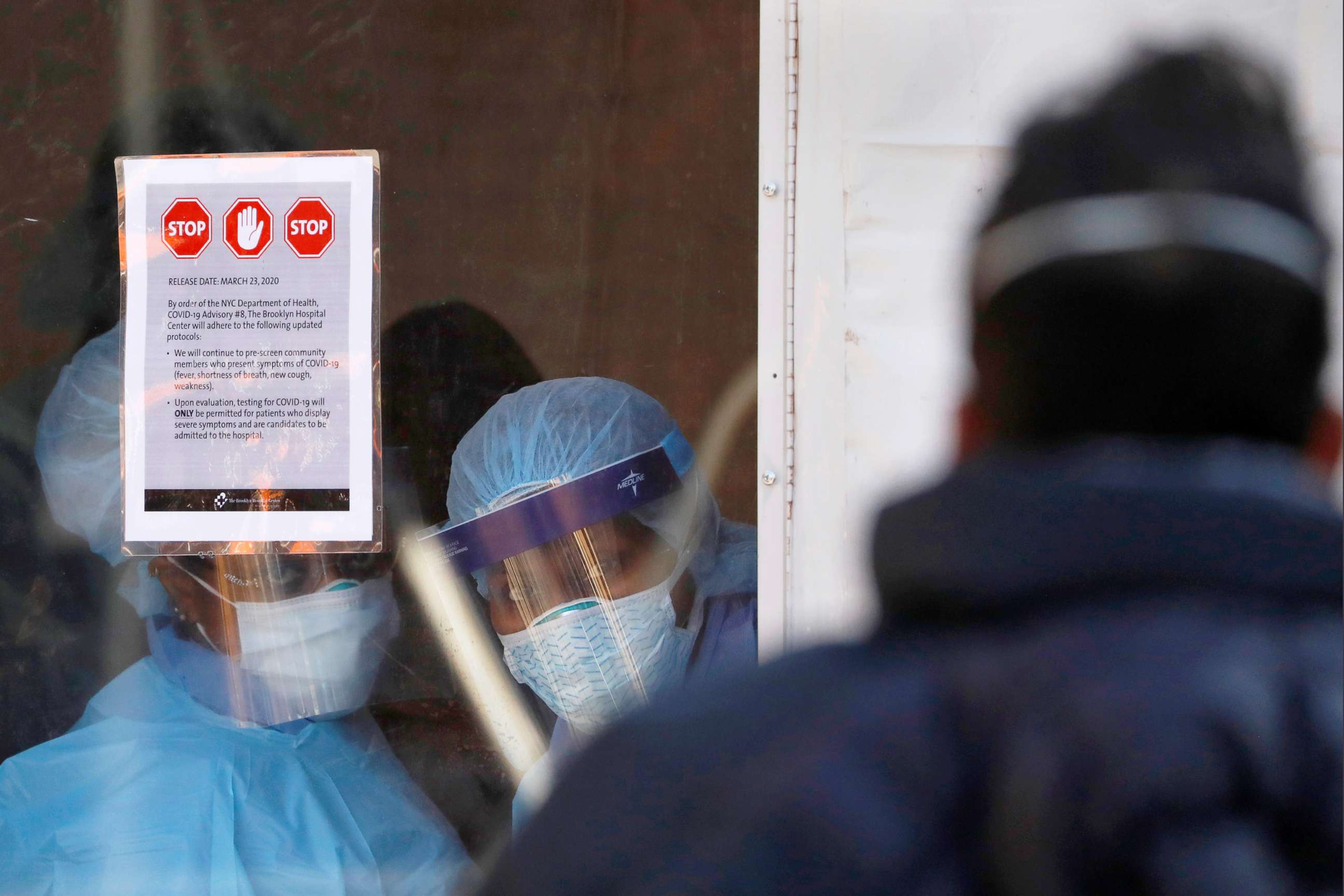

It's a critical, urgent question in the battle to save American lives -- and one that a growing number of institutions, including one of New York's preeminent medical centers, will attempt to answer.

Dr. David Reich, the president of Mount Sinai Hospital in Manhattan, said his team of experts is in the process of tracking down possible donors -- recovered patients whose blood antibodies could potentially curb the virus in the sickest patients.

“It’s great that we have some avenues and some options to try to improve the treatment of our patients,” Reich said in an exclusive television interview with ABC News' Diane Sawyer. “And we certainly hope the crisis in New York will abate soon and that we can save as many people as possible from this terrible disease.”

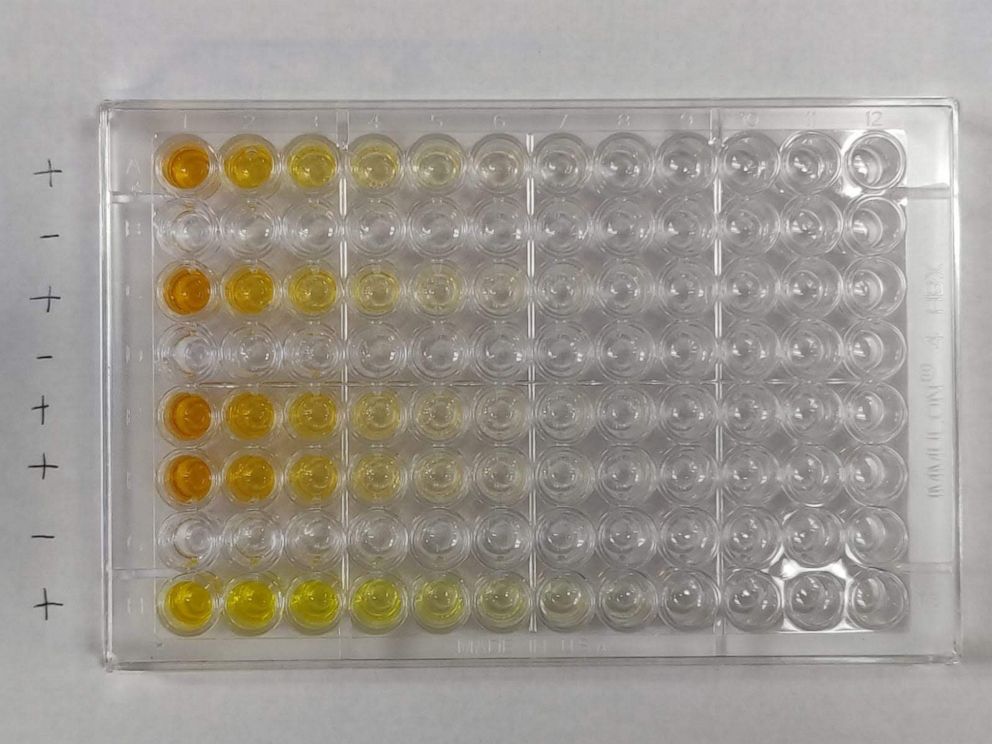

With an approved vaccine still months away at best, the experimental treatment offers a ray of hope for medical professionals and patients alike. The premise is simple: plasma isolated from blood donated by those recovered patients is transferred to a sick patient using an IV, which may then boost a patient with COVID-19's own defenses.

“Am I right that you are about to see if the antibodies of a recovering person can save the life of someone who is critically ill?” Sawyer asked.

“That is concept, Diane,” Reich said. “The idea is that -- as has been done in multiple previous epidemics -- if you give the plasma, the portion of the blood that contains the antibodies, from someone recovering from an illness, a viral illness like COVID-19 or Ebola -- it may help the patient overcome the disease.”

The practice is called convalescent plasma, and medical professionals in China have already used it on at least five critically ill patients with COVID-19, according to results published Friday in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA).

The clinical data in China shows the five patients were in critical condition before the plasma infusion. Afterwards, according to the study, they began to recover.

“These preliminary findings raise the possibility that convalescent plasma transfusion may be helpful in the treatment of critically ill patients with COVID-19 and ARDS, but this approach requires evaluation in randomized clinical trials,” the JAMA study concluded.

Mount Sinai is not alone in this endeavor. A group of the nation’s top academic institutions recently launched a website with protocols for those interested in experimenting with convalescent plasma. A spokesperson for the Food and Drug Administration said Friday that a small but growing number of institutions are developing protocols for the procedure.

“We believe it can be disease-modifying and reduce duration and severity in some patients,” said Dr. Michael Joyner, a physiologist and anesthesiologist at the Mayo Clinic, one of the institutions mobilizing to start this.

Healthcare providers in the United States are optimistic, but the experimental therapy will take time to fully develop and is not without risk – and should not be perceived as a “magic bullet,” Reich warned.

“We can never know with a new therapy if we’re causing more good than harm or more harm than good, and that’s going to be always a concern for us, but we believe based upon the history of this therapy that it is the right and ethical and moral thing it to do in the face of a growing crisis,” he said.

Even so, Mount Sinai and others are moving forward. Reich said his team will aim to begin convalescent plasma treatments in the coming days, but the first order of business for medical staff is to find recovered patients – ideally those with a particularly high antibody count that could support more than one current patient.

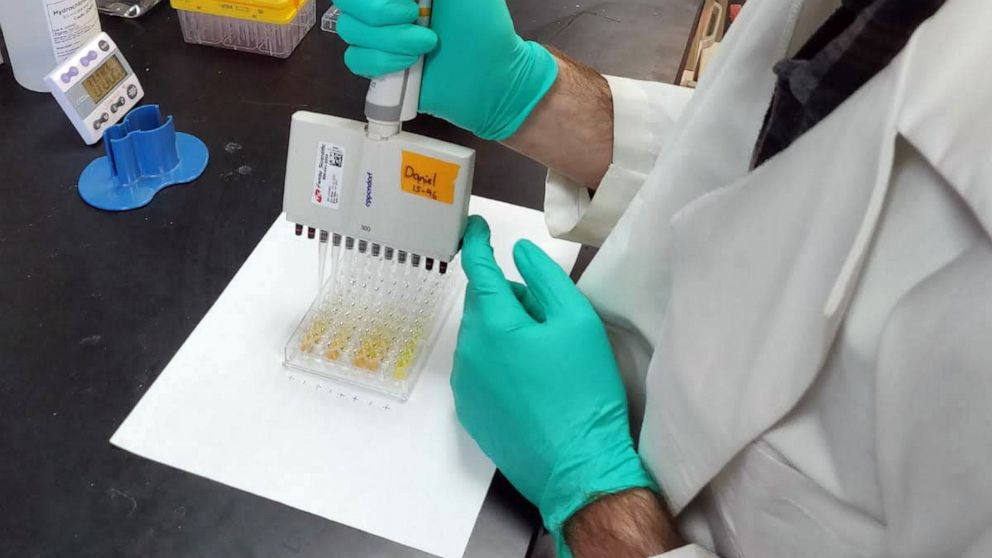

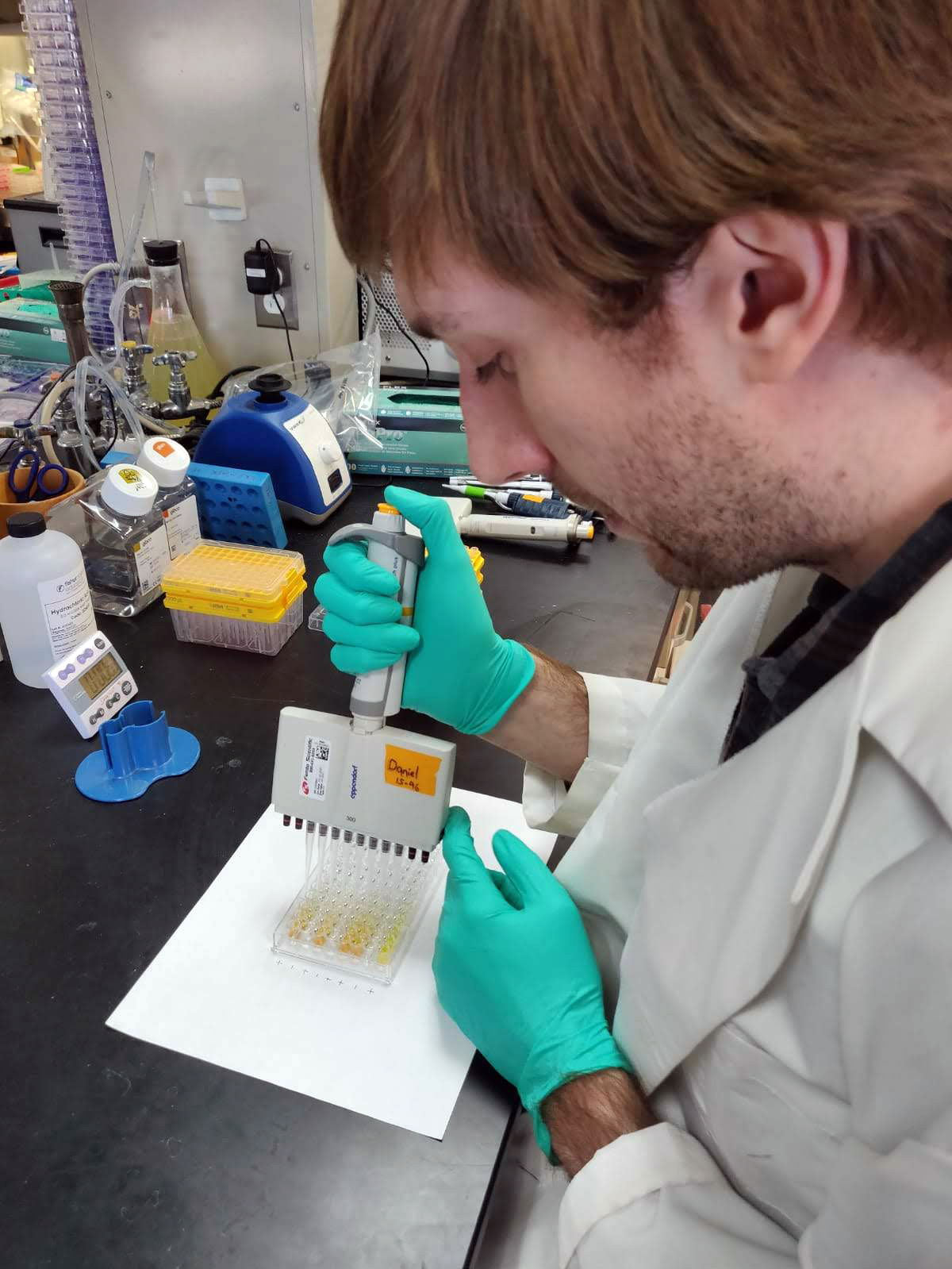

A lab team at Mount Sinai has been working around the clock in recent days to find candidates, according to Reich. Prospective donors must be at least 21 days removed from the initial symptoms and be able to provide documentation of a positive case.

So far, the community has responded: the hospital says it has already received thousands of offers to donate blood. One of those recovered patients is 31-year-old Rich Bahrenburg.

“It feels like at least if I have to go through this and I’m one of the lucky ones who doesn’t have to be on a ventilator, one of the lucky ones who doesn’t have to be at the hospital, I feel like I owe it to people as a whole to try and give back if I can,” Rich told ABC News.

Reich and his Mount Sinai team are hoping others like Rich follow suit.

“I think that it’s beautiful if people who are recovering from the illness can, in the spirit of donation and helping others -- that some of them will have that capacity in having very high levels of immunity,” Reich said.