5 people get real about the pain of eating disorders and the 'process' of recovery

Eating disorders are deeply personal, but one thing applies across the board – they don't discriminate.

"Anyone can get an eating disorder," said Damola Akintunde, 24, a photographer who battled anorexia nervosa starting at age 15. "It's not restricted by gender, race, class, religion."

"You can live in a 'healthy-sized body' and be suffering from anorexia. You can live in a 'healthy-sized body' and be struggling with binge eating disorder. You can't look at someone and know what they're struggling with," said Reba Tobia, 27, who is recovering from anorexia and created The Brave Box, a self-care box for those in recovery, to be reminded of their strength.

Despite similar rates of eating disorders among people of all backgrounds, people of color are significantly less likely to receive help for their eating issues, according to the National Eating Disorder Association.

Five individuals opened up to "Good Morning America" about their personal battles with an eating disorder and their recovery process to encourage others to get help. According to the NEDA, early intervention is key and friends and family are critical to encouraging loved ones with eating and/or body images to seek help.

The ups and downs of recovering and finding 'body neutrality'

Damola Akintunde, 24, visual artist, photographer and creator

"[Around the age of 15], I basically would restrict my eating so I essentially had anorexia nervosa at the time and did not know I was dealing with that. I didn't get a formal diagnosis until college. ... It was like a coping mechanism to a lot of the stress I was dealing with at the time.

"I wanted to take control of myself and instead of, like, finding positive ways to do that, I kind of self-harmed as a way of shrinking myself to make myself physically smaller.

"[My friend and I] were just hanging out one day and she's like, 'I noticed you don't ever finish your meals,' and that was a really shocking moment. At one point, I got defensive, and then the next moment I was like, 'But you're actually right, that's true.' And then she was like, 'Yeah, you might have an eating disorder.' And I didn't really put two and two together until she had pointed out and even after the fact, I think I was still in a little bit of denial.

"I think a lot of people think it's like you're all of a sudden recovered, but there are a lot of ups and downs where I was like, 'OK, I'm doing good this day,' and then the next day might not feel so great. ...You just make sure that you're at least trying and you know, getting the support that you need.

"'My experiences are valid.' I wish I heard that, because it was really easy for me to feel like I'm the only one dealing with this in this way. ... I want people to feel like there's not a stigma associated with experiencing it, and be able to talk freely with the people that you love about it because they do care about you and they do want you to get better.

"I have gotten to the point where I kind of have embraced more of the idea of like, body neutrality, where I don't feel like I have to feel good about myself 24/7. If I have a day where I'm not feeling good, I know that's not going to derail my entire day or my entire week. ... I can sit in that and feel it. And the next day, I'm like, 'OK, we're good.'

"I just have a newfound appreciation for what my body does for me. I appreciate the fact that I can look at food as like a source of nourishment [and as a way of] bringing joy into my life positively. I love cooking, I've always loved food. But when I look at it, I don't see it as something that's going to harm me. I can kind of have a newfound appreciation for what it does for me and my body.

"My photography has helped kind of bring that into my life as well, like analyzing what it looks like to be a black woman, and kind of sitting in my own truth in a way [that] makes me feel really good about myself."

Confronting life-long struggles with body image

Colleen Wener, 23, graduate student studying clinical mental health counseling at Trevecca Nazarene University

"People assume eating disorders are all about the food. And while that is a piece, it's honestly really a small piece and it's so much more about body image, and trauma, and anxiety, and depression and so many other things. It's really rare that someone just has an eating disorder. There's usually something else there that goes far beyond food and their body.

"I first started struggling with body image when I was about 8 years old, and then I first dieted when I was 10.

"When I was like 16 or 17, I really wanted to pursue a professional career [in dance]. I didn't see anyone who looked like me in dance magazines and dance companies. I felt that if I wanted to have a chance at a career, and if I wanted to be successful ... I had no choice but to change my body. ... Wanting to change my body totally wasn't all my eating disorder was about. It actually was about a lot deeper things, like my trauma history, and anxiety, and depression, perfectionist personality and things like that, but dance really was a big part of it.

"I didn't start recovering from my disorder until I was 19. ... It was a pretty long process of really damaging my body. ... It ended up that the summer before my sophomore year of college, one of my best friends from growing up, she also struggled with an eating disorder. ... We went into New York City, and we were seeing a Broadway show and going out to dinner, and I actually ended up finding out throughout the course of the night that many of the friends that she had with her were people that she had met in treatment. I was hearing them talk about their eating disorders and recovery [and] going to treatment, and the things that they were doing in therapy and I really realized, 'Wait, this sounds like what I'm doing. This sounds like what's going on for me, and they're going to treatment for this. And they're going to therapy.'

"When I went back to college that fall, I started seeing a therapist. I was still very much in denial and wasn't saying it was an eating disorder. I was just like, 'Oh, it's just anxiety,' and while you know, working through things, as far as my anxiety was helpful, once I started peeling back those layers, I realized that it was an eating disorder, and that was a deeper problem. So, once I acknowledge that and came out of that denial, I was able to like actually move forward in recovery instead of just remaining really surface level.

"It wasn't until after one of my relapses that I realized that I needed to reevaluate our relationship with dance. I needed to take a step away from dance...Remaining in that world was making it hard for me to really push forward into true lasting recovery, as opposed to kind of just being surface level and being like, 'OK, I'm not engaging in these behaviors anymore, but these thoughts are still here, and I still have a lot of urges.'

"It's really cool to be able to be in this place in my recovery where I'm able to love dance again. … [In the past], it was about changing my body … [now] it's about being in my body and loving my body as I'm dancing.

"I'm currently studying to get my masters in clinical mental health counseling, which will prepare me to become a therapist. My personal journey of recovering from my eating disorder and also living with PTSD and anxiety and depression really is what made me want to go into the field, especially because of how much the therapists that I've had have changed my recovery [and] have helped me help myself in ways that I couldn't do without their guidance.

"While sometimes asking for help is viewed as a sign of weakness, it's really the opposite ... asking for help is a huge sign of strength."

Eating disorders are not a choice. Recovery is something that a person has to choose.

Sam Dylan Finch, 28, lead editor for mental health and chronic conditions at HealthLine.com

"One of the really big assumptions that I have in some ways internalized for myself ... is just this idea that eating disorders are somehow a choice. But the reality is that eating disorders are very complex and they are mental illnesses.

"I've always had anxiety around food. When I was a kid, I was a very picky eater. I really struggled to try new foods ... it developed into this avoidant behavior around food, where I would only eat things that felt safe to me ... and then, probably when I was 13 or 14, it morphed into something a little bit different.

"I definitely had anorexia, although I didn't know that I did. I think that for myself, I just had a very specific idea of what anorexia was, and it didn't align with what I was doing. ... I thought, like, 'Oh, anorexia is when you have an obsession with your weight, and you're obsessed with being thin,' and in my mind, I thought it was just like a vanity thing. For myself at that time, that just wasn't what I was fixated on. ... But really underneath all of that, it was more so fueled by this need for control, this desire to kind of like [be] checked out and emotionally really numb.

"In so many ways beyond just being queer and transgender, I think being a kid who ended up having mental illness and a lot of things that I think most parents, even supportive parents, aren't prepared for, I think really threw [my parents] for a loop. I think that I internalize this idea that everything that made me different from my family made me a problem. A lot of how I coped with that was to just repress, internalize, and ultimately tried to like conceal who I was because in my mind that seemed like the safest thing to do. And also, that meant that I was being good, because it wasn't imposing on anybody else's idea of who I was supposed to be.

"Part of what folks don't necessarily realize is that malnourishment affects your brain in really significant ways. Your ability to make decisions, to regulate your emotions, to have some level of self awareness, are really deeply affected. So it makes it difficult to actually know, 'Wait, I do need help.'

"Recovery is something that a person has to actively choose and be ready for and it's also a really difficult and long process.

"There's this idea that unless you're literally falling apart, and everything's coming undone, that's when you get help. In reality, it's always good to be reminded, you don't have to wait.

"I think the most helpful support that I've gotten has actually been some of the simplest but most meaningful. Having people say, 'I'm worried about you and I just want you to know that I'm here.'

"For the longest time, I told myself I was a slow walker, because I walked really slowly. When I started getting better nourished, my pace changed. There's a spring in my step and color in my face and just seeing, 'Oh, how I move through the world changes when I'm taking care of myself, how I show up for other people changes how I feel in my body.' That doesn't mean it's like an easy process. Recovery is very long and difficult, but I think there are a lot of moments where I look back and I see how I was basically living half a life. ... I was really denying myself a lot of the experiences that would have brought me happiness."

'A sense of control'

Neesha Arter Kuratek, 28, writer and author of the memoir, 'Controlled'

"With eating disorders, people think it's this aspiration to be skinny or be a model or an actor. I look at it as a source of control, when your life is spiraling out of control.

"When I was 14 years old, I had convinced my parents to let me go visit some family in another state for New Year's Eve. My parents both thought that I was safe because I was visiting family, but I was actually assaulted by two family friends that I really had no reason to mistrust or be skeptical at all about. After that night, I knew that I had done nothing wrong. I thought it was very black and white, however, when my aunt and two cousins all found out, they blamed me and they took the side of the two boys, which then forced me to blame myself.

"When my parents found out, they took my side, but they wanted justice. I just wanted to go back to being a teenager and living my life -- sleepovers, volleyball, everything that I was doing before. Instead, I had to relive the story over and over with detectives and lawyers on camera. I had to do a rape kit. It was really traumatizing. That was when I started to really restrict my eating and it ultimately led to a full-fledged fight with anorexia, because in my head it was [the] loss of innocence.

"It was less about weight and numbers. It was just I thought that if I could look like a child again, who I was before this happened ... it very much was a sense of control. The way that I was coping with it was to eat less to kind of just disappear in a sense, and it was the only way that I could manage all the emotions.

"[My parents] have just been incredibly understanding. ... I remember freshman year when I was writing this book and working on it, I called my mom and I said, 'You know, this is really difficult,' and she was the first person to go find me a therapist in Orange County.

"A big reason why I wanted to write this book was for parents, for others going through this, because there's a lot of blame, and people blame others or themselves. ... Sometimes bad things happen and you have to find your best forgiveness and move forward.

"I think [recovery] is going to be a process forever. ... I think for me, it's just accepting it and then trying to help others. That has been the best part of my recovery, is trying to give people the tools to know that they're not alone. And they're going to be OK, because there's always hope."

Recovery and bravery

Reba Tobia, 27, founder of The Brave Box

"I definitely believe that an eating disorder is like having a friend in your brain. You kind of start off with this friend, thinking that she has your best interests in mind. She's going to help make your life better and she or he is going to be there for you when other people might have not been and you might be in a really vulnerable position. So you latch on to this friend.

"As you spend more time with this friend, you notice your life getting smaller and smaller, and you notice her getting meaner and her demands getting harder. And, yet, you're trapped with her and you feel like you can't survive without her. You can't let her go. And it's an awful and grueling way to live. It's a way so many people live in silence. It's the way so many people live thinking maybe it's normal.

"I believe in full recovery, I'm just not there yet. ... I have been in recovery from anorexia for the past 5 1/2 years. My eating disorder really started when I was about 12. I definitely was more in tune with other people's bodies. I was definitely in tune with what other people around me were eating, their interactions with food. ... I was about 16 [when] my eating disorder kind of really reared its head and kind of clenched on, and when I was 18 [it was a] full-blown eating disorder. ... I held it definitely in secret for a while as my eating disorder progressed.

An eating disorder is like having a friend in your brain ... You kind of start off with this friend thinking that she has your best interests in mind.

"Your body might not change and it doesn't mean one is better than the other, but since my body did change, and people started complimenting me on it, 'You look great. What are you doing?' And at the time, those comments felt so good. And nothing was wrong with my body before -- nothing is wrong with anyone's body before -- but those comments really kind of reinforced my eating disorder. And as it progressed, those comments kind of changed from, 'Oh my god, you look so good,' to, 'Oh my God, are you OK?'

"I was so sick that hearing people kind of recognize my sickness felt really good. ... When I was 22, I first started recovery and that was after I engaged in a lot of physical activity [and] over-exercising ... I started seeing a dietitian and I went into the process thinking I'm going to see a dietitian to find out how I can run faster. ... I was so oblivious and didn't want to accept that there was a problem. So, it took me a long time to accept that something was wrong.

"For my recovery, I didn't have this huge support network ... I didn't have 20 friends. I didn't have aunts and uncles and all these people calling and helping me or sitting with me and eating three meals. ... It was really hard for me to hear those stories. And I knew that the people in my life didn't really know how to, or at least struggled with, how to interact with my eating disorder. ...They wanted to support me, but they didn't know how.

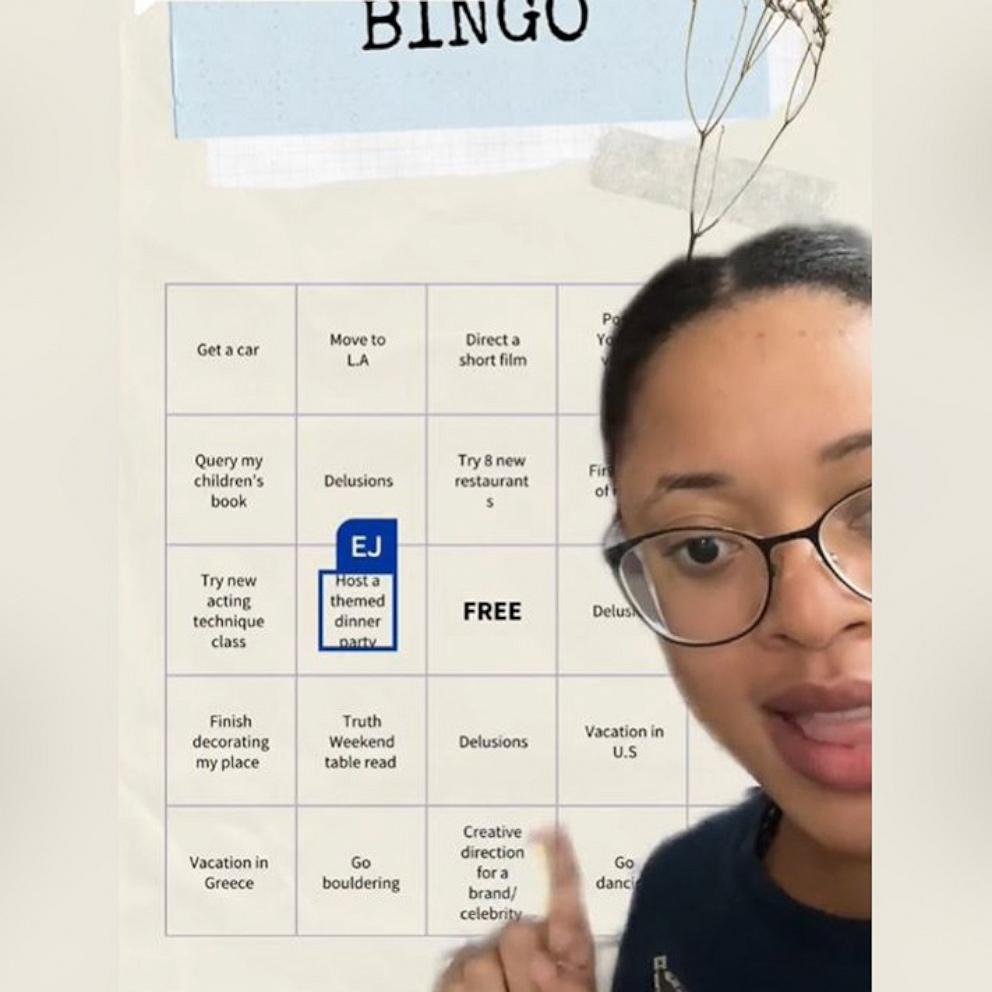

"It just hit me [that] there's gotta be other people out there that are struggling like me. ... It just popped into my mind like, why not make a box that I could put things that I felt like were really helpful to my recovery and are helpful right now to my recovery, that someone could order for themselves or that a loved one could order and send to someone in treatment, or send to someone who was struggling in a way that was supportive?

"I always loved the reminder that I'm brave and that I can do hard things ... so this kind of idea of making a [Brave Box] that could show support through a loved one or just to yourself. (The Brave Box includes several items that are dedicated to bringing courage, hope and body positivity to people struggling with an eating disorder. A portion of all proceeds go to the Multi-Service Eating Disorder Association in Newton, Massachusetts.)

"If you have a sticky relationship with food, if you have a bad relationship with your body, if you feel even an inkling like you're struggling, you are struggling enough. … You deserve support, and you deserve love, and you deserve community, and you don't need to wait until you're sick enough. And you don't need to live life this way. There's such a different way to live."

Editor's Note: These essays have been edited for clarity.

For more information on eating disorders, including warning signs and how to find support and help, visit the National Eating Disorders Association.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, please call the toll-free National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 800-950-NAMI.