Parents may be the secret weapon in the battle against childhood obesity: Study

About 14 million children and adolescents in the U.S. are obese.

Being overweight as a child is associated with obesity as an adult. What is even more concerning is that since 1970s, rates of childhood obesity have tripled, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Overweight or obese children are at a higher risk of developing medical problems, such as Type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and sleep disorders like sleep apnea, according to the CDC.

But what strategies can parents use to help their children maintain a healthy lifestyle?

Researchers from the Pennington Biomedical Research Center recently tested a new program known as DRIVE (Developing Relationships that Include Values of Eating and Exercise), which emphasizes parental involvement in reducing child obesity. Their results were published in the June 2019 issue of the Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior.

“Parents being a source of change was the factor that made this program work,” said Dr. John Apolzan an assistant professor of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism at the Pennington Biomedical Research Center, and one of the authors of the new study.

Researchers took 16 families with children ages 2 to 6 years old, and randomly assigned them to one of two treatment groups: a health education group, or the DRIVE group, which had a more rigorous weight-management program.

The health education group was mailed pamphlets on nutrition and parenting strategies for change, but did not receive any coaching or personalized interventions.

Meanwhile, families in the DRIVE group met with a psychologist or a nutritionist, and were challenged to reduce screen time, engage in more physical fitness activities and plan healthier meals.

Families in the group that was mailed pamphlets did not receive behavioral interventions with follow ups.

Researchers followed the families in both groups for 19 weeks, and monitored changes in their weight, waist circumference and body mass index.

According to Apolzan, there was less of an increase in the BMI of children in the DRIVE group, with average gains of 0.6 pounds at nine weeks and a 1.3-pound weight gain at 19 weeks, which he said was attributable to normal growth spurts.

Some of the parents in the DRIVE group were able to lose weight as well, averaging a 7.5-pound weight loss by the end of the study.

Children in the less rigorous health education group gained 3.3 pounds nine weeks into the study, and 5 pounds at 19 weeks -- significantly more than their DRIVE counterparts.

Researchers believe these weight increases are due to a less structured weight management program.

Dr. Apolzan emphasized that the DRIVE study was not a weight loss study, but rather focused on weight management in children at risk for obesity -- researchers were focused on making sure that families adopted healthier lifestyle practices.

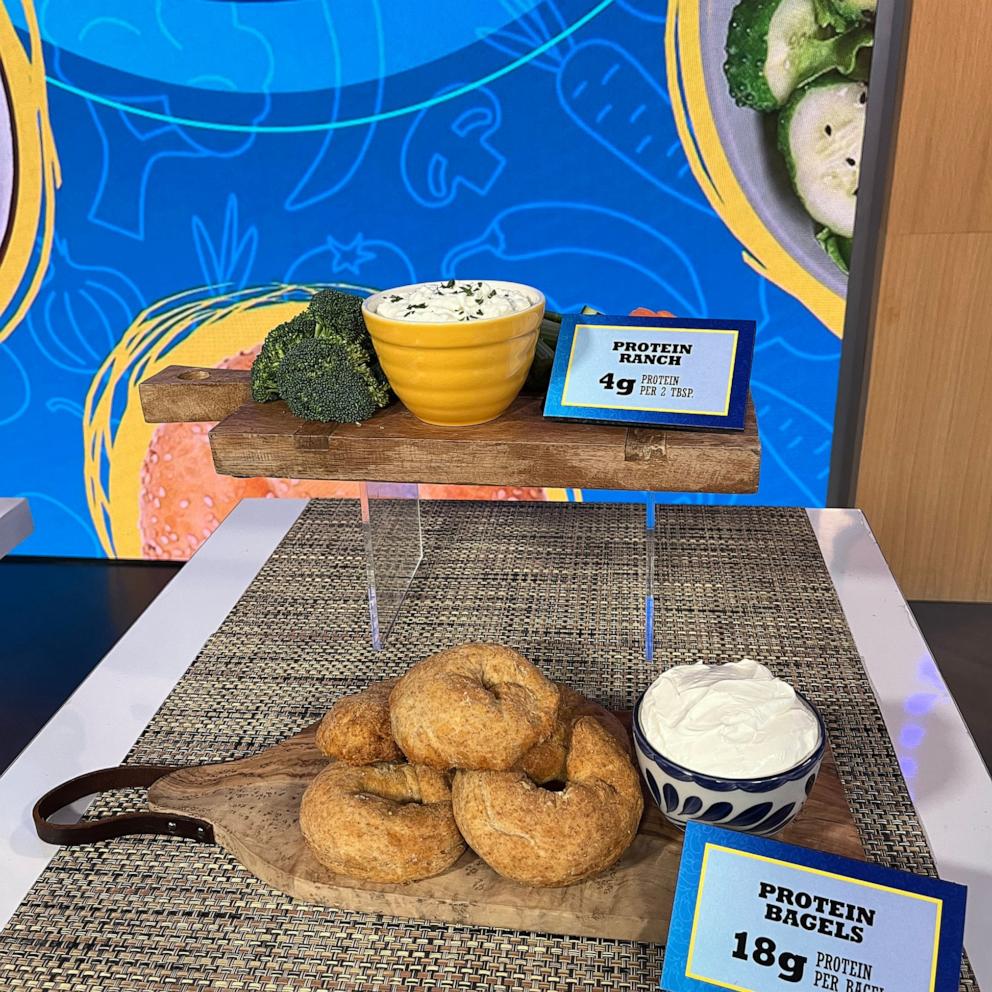

Helping kids stay active, low-sugar snacks, and incorporating more fruits and vegetables are some steps that families can take to being healthier.

Tiffany Best, M.D. is completing a fellowship in child and adolescent psychiatry. She works with the ABC News Medical Unit.