Can we nudge our way to responsible opioid prescribing?: COLUMN

If you nudge a heavy object with your index finger over and over, it may not move. But if enough people nudge together, you may create real change.

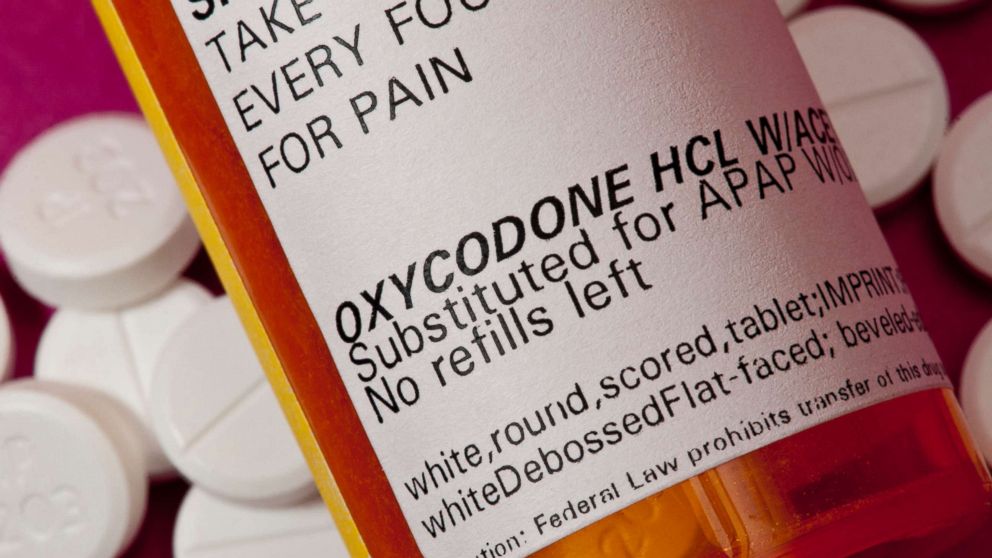

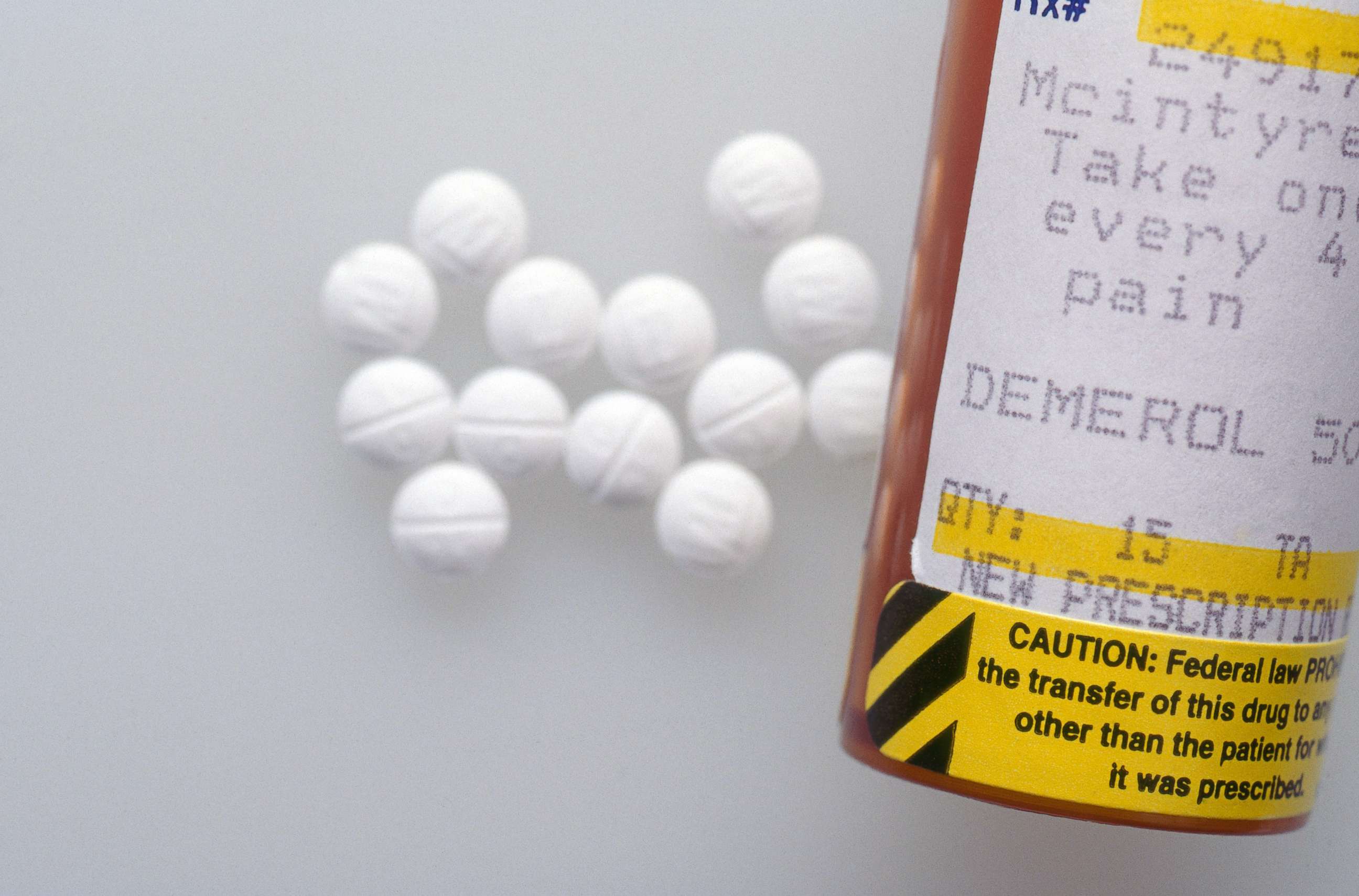

The same goes for public health issues on a population level, including the opioid crisis. America remains in the lead as the country with the highest rate of opioid use in the world. A report from the Mayo Clinic published Wednesday in The BMJ concludes that opioid use and average daily doses have not substantially declined over the course of the past decade.

The researchers looked at 48 million people in Medicare populations between 2007 and 2016. Rates of opioid use did slow down within the later years, but the doses are still higher than they previously were and there has been no reduction in overall prescribing rates in the Medicare group. This is despite increased awareness and attention to opioids. When the status quo isn’t working -- and it isn’t -- we need new approaches. Those nudges from different angles might be a good place to start, and we have to learn what works and what doesn’t in changing prescribing decisions.

The hope, in the public health field, is that if the problem is tackled from multiple angles -- addiction detection and treatment, increased risk awareness, and reducing access to pills -- there may be change on the horizon. One of the angles, of course, is up to the doctors: prescribing opioids.

This means making sure that doctors are prescribing responsibly, and only when they are really needed. Some techniques to reduce high prescribing rates have shown promise: defaulting to fewer pills at a time, limiting refills, or having to explain reasons for giving more pills. Other techniques, like increasing visibility of who is prescribing what might help in theory but have yet to show measurable impact.

As a child psychiatrist, I view the understanding of human behavior as one of the most important places to start in driving any change. I spend most days at the hospital trying to figure out what drives people to make decisions. What motivates a teen to stop using drugs? What techniques can parents use to encourage kids to follow rules and have fewer tantrums? Extrapolate that beyond the home, and beyond parenting. We make decisions every day, not as curves on a research graph but as people. People aren’t always rational in the ways that we might expect them to act.

Economist and Nobel prize winner Richard Thaler, along with legal scholar Cass Sunstein, considered this level of irrationality as they introduced the behavioral economics theory of the "nudge" and how it affects choice in their book, "Nudge." In this theory, people are “nudged” to make a different choice, all without changing the economic incentives or being forbidden from any existing option.

Dr. Anupam B. Jena, associate professor of Health Care Policy at Harvard Medical School and economics expert, explained the idea behind the nudge.

“The idea behind a nudge is simply that an intervention can nudge an individual to act in a way that they would, in fact, choose to do, but do not for a variety of reasons: time pressure, competing for cognitive tasks, choice overload, etc,” Jena said.

The key here is to lower the barriers that get in the way of people making worthwhile or effective decisions that could lead to larger change.

We see these forces silently at play in what they call the “choice architecture” of everyday life. Previous research has described that getting closer to a goal results in increased motivation forward. When counseling parents on how to nudge their kids to exercise more, my first step is figuring out how to make the task seem convenient, quick, and a psychologically simple choice. Making the exercise goal smaller, shorter, and less confusing helps.

Convenience comes into play in day-to-day decisions. If the goal is to drink more water, you may find that easier to do if your water bottle is sitting next to you and easy to grab. If you have to get up and go find water -- if it’s in any way inconvenient -- it may be enough for you to decide that you don’t want to drink it.

Experts have started applying behavioral economics to reducing unnecessary opioid prescriptions. A recent study from JAMA Surgery found that lowering the standard number of pills in a prescription from 30 to 12 in the electronic medical record resulted in 15 percent lower rates of opioid prescribing across a health system -- it’s automatic and the doctors don’t need to think about it. The authors describe the strategy in their study as a “simple, effective, cheap, and potentially wide-reaching intervention that can be harnessed to help change the culture of opioid overprescribing among providers.”

The results are unsurprising. Research by psychologists has shown for years that people are more likely to do something if they have to opt-out of it instead of opting in; that’s why organ donation is the default setting on the backs of driver’s licenses. People are influenced by peers; they might think that if something is set as the default, most other people are doing it that way. Or the simple act of having to change the default is too annoying or time consuming for people to bother with it. They keep the default.

Another study, published recently in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons, shows the spillover effect of making a change. When doctors changed their post-operative prescribing for one procedure to follow new guidelines, those habits trickled down into their prescribing behavior for other, unrelated procedures. Once doctors changed their practices to safer ones, the path of least resistance became to keep going with the new, safer approaches. They’re now familiar, and they realized the impact of their actions. The main hurdle to overcome was the initial change, which required a nudge.

“Post-operative prescribing and prescribing at hospital discharge are also critical periods when patients are potentially highly susceptible to adverse effects of opioids,” Jena added. “Default prescribing as well as defaults that require physicians to check prescription drug monitoring programs or justify concomitant opioid-benzodiazepine use may also be impactful and should be studied.”

Nudges aside, other efforts are being taken to consider human behavior in public health efforts. Narcan, the opioid reversing agent, is now available over-the-counter in 46 states, significantly reducing the time and effort required to get it.

Instead of reinventing the wheel, people should learn from one another. In one study just published in JAMA Network Open, following guidelines to prescribe cholesterol-lowering medications almost tripled when an electronic dashboard was added to the medical record. In the dashboard, the best-recommended prescription was the default. To change it, they had to enter an explanation. If that strategy works for other medications, does it work for opioids?

“The key question is what impact did this have on patients?” Jena said. “To be sure, this is an important finding but what is also critical to know is a) was pain adequately controlled for all patients, b) did patients seek opioid prescriptions elsewhere to fill the gap (either from other doctors, family members, or friends?), and c) do we observe reductions in transitions to long-term use due to the fewer pills prescribed?”

It doesn’t matter how many nudges are in a push if there is no real-life impact. The next avenue for the study is to capture that data while keeping in mind the real people affected.

Neha Chaudhary, M.D., is a child psychiatrist at the Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School and co-founder of Stanford Brainstorm. She is currently working with the ABC News Medical Unit. Her views do not necessarily reflect those of ABC News.