Measles: What we know about the disease

Public health officials have begun taking radical steps to abate the spread of measles as outbreaks continue across the country.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that there have been 314 confirmed cases of measles spanning six outbreaks between Jan. 1 and March 21 this year. If the virus continues to spread, it’s possible that the number of outbreaks this year could outpace the 17 total outbreaks in all of 2018.

The cases span 15 states: Arizona, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Georgia, Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan, Missouri, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Texas and Washington. However, cases tend to be largely localized in areas of unvaccinated people. In New York City, one of the hardest-hit areas, there have been 181 cases of the virus, while Clark County, Washington, has 74 cases and Detroit, Michigan, has 22 cases.

Some areas are beginning to take drastic measures to stop the spread, though. Rockland County, New York, where there have been 153 cases within a six-month period, declared a state of emergency on Tuesday and banned minors from public places, like churches and malls.

“It’s incredibly serious. Measles is one of the most exquisitely contagious infectious diseases that we know of,” Dr. Alan Melnick, Clark County health officer, told ABC News. The virus can linger in the air for hours.

Here’s what you should know about the measles.

Measles is highly contagious and spreads through airborne particles in coughs and sneezes

Ninety percent of people who haven’t been vaccinated for measles — including babies, the elderly, pregnant women and immunosuppressed people — can contract the virus if they are exposed to it, according to the CDC. Additionally, they are more likely to have a severe form of the disease and are more at risk for long-term consequences or even death.

Measles outbreaks usually occur in clusters in areas where people have not been vaccinated. The virus can linger in the air for two to three hours after an infected person who sneezes or coughs leaves the area.

Bracing for more cases, Melnic said that if you suspect you or your children have the measles, do not go to a walk-in clinic, emergency room or doctor’s office first. Instead, “call the emergency room before you go in and they can arrange to see you safely so you don’t expose everyone else in the emergency [room] or the waiting room.”

Measles can also cause life-threatening complications

Before the vaccine came out in 1963, three to four million people were estimated to be infected with measles every year, with thousands developing complications that led to hospitalization, death or lifelong disability.

The CDC estimates that one to two people out of every 1,000 with measles will die from a complication of the infection. One out of every 1,000 will also develop severe swelling in the brain, called encephalitis, which can lead to deafness or permanent brain damage. And one out of every 20 kids will get pneumonia, the most common cause of death with the disease.

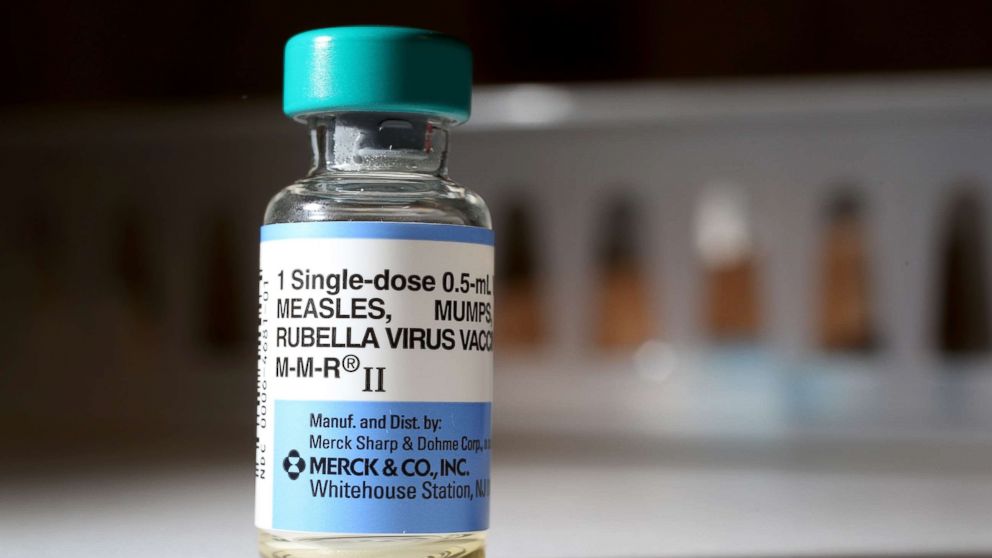

Measles is preventable with vaccines, which benefit the greater population

The surest defense against the virus is the Measles-Mumps-Rubella (MMR) vaccine, which should be given in two doses — one at 12 to 15 months of age and another at 4 to 6 years of age. The MMR vaccine works; one dose is 93 percent effective and two doses are 97 percent effective at protecting against the measles virus. This should provide lifelong immunity.

In Rockland County, 82 percent of those infected had not received the MMR vaccine and 10 percent had unknown vaccination statuses.

“If you can prevent your child from suffering from a devastating disease by something as simple as a shot, why would you not?” New York State Health Commissioner Dr. Howard Zucker told ABC News.

By giving your child the MMR vaccine, you are also helping to establish “herd immunity.”

“Herd immunity is when you have the vaccination rates high enough [that] you prevent the spread of a disease in a population,” Melnick said. “For measles, because it’s as contagious as it is, you need well up in the 90s — around 93 percent. … [In Clark County, Washington,] schools, the vaccination rate is 78 percent.”

Herd immunity can help prevent infection in those who cannot get the measles vaccine due to medical conditions.

Dr. Jennifer Ashton, ABC News’ chief medical correspondent, said that if there’s an outbreak in an area, parents of unvaccinated kids should take the same precautions as they would with the flu — washing hands, avoiding contact with sick individuals and coughing and sneezing into their elbows as opposed to their hands.

For infants younger than 12 months who are traveling internationally, the CDC recommends administering one dose of the vaccine at 6 months of age, but the child will need two additional shots after 12 months to confer immunity.

Health officials also recommend checking the vaccination policy at your child’s daycare center and school as the laws regulating vaccinations vary by state.

Dr. Azka Afzal and Dr. Janvi Todai are resident physicians in Houston and Amrit K. Kamboj, MD, is an internal medicine resident. They are members of the ABC News Medical Unit. Jamie Felzer, MD, MPH, is an internal medicine resident from Scripps Clinic in San Diego, California, and works with the ABC News Medical Unit.

This article was updated on 3/27/19.