After marijuana edibles helped dying Holocaust survivor battle Alzheimer's, his family's foundation pushes for more research

A Massachusetts family’s experience giving marijuana edibles to their dying patriarch is set to kick off a desperately needed investigation into how cannabis might treat some of the more troubling symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease, a condition that affects 5.7 million Americans.

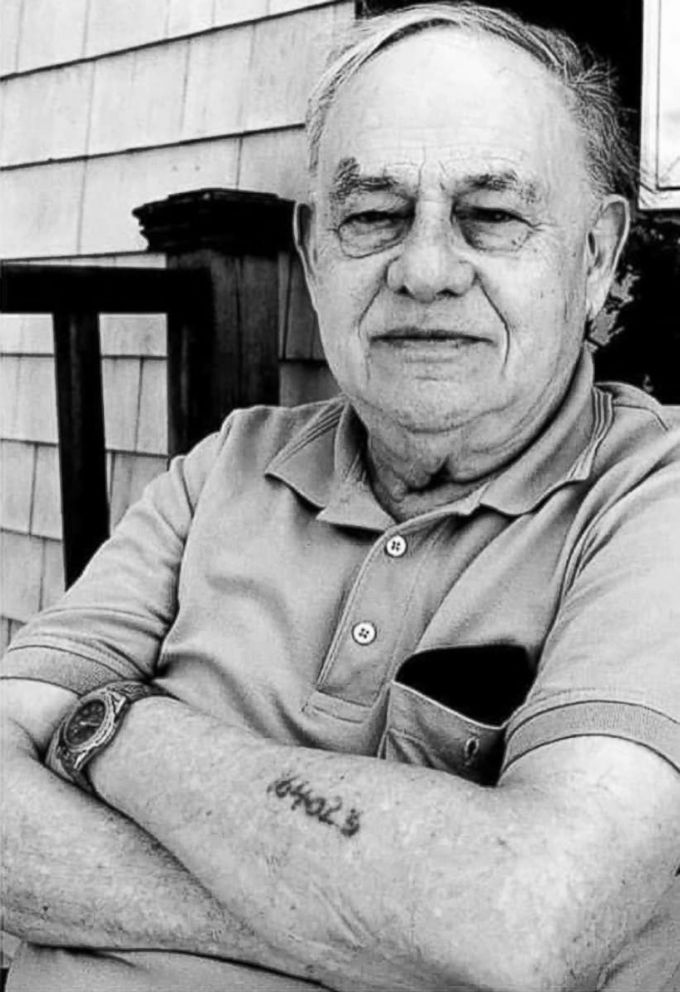

Alexander Spier spent three years during the Holocaust in Auschwitz and other concentration camps as punishment not only for his heritage but also because he had fought against the Nazis with the Dutch Underground. Spier was eventually able to emigrate to the U.S. from Holland in 1945, where he began working as a watchmaker and jeweler before moving into real estate and construction.

Today, Spier’s family runs the multimillion-dollar company that he built, Mayfair Realty & Development Corporation. They’ve also carried on his tradition of philanthropy through the Spier Family Foundation, which has supported a variety of medical research through different hospitals in the past.

Harvard’s McLean Psychiatric Hospital is one of those institutions supported by the Spiers. And now, it’s partnering with the family to research the potential benefits of medical marijuana on Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia.

Spier died of complications related to Alzheimer’s in 2017. His final two years were characterized by rapid decline, which his son, Greg Spier, described as torturous.

“It was the most difficult time of my life, having to see him deteriorate. My father spoke five languages, and he was speaking Dutch and German, reliving the three concentration camps he survived,” Greg Spier said, recalling how his father often pleaded, “Where is my mother?” in German.

Alex’s story is typical for many of the 50 percent of Alzheimer’s patients who develop so-called neuropsychiatric symptoms of the condition, characterized by agitation, anxiety, depression, psychosis, wandering and pacing.

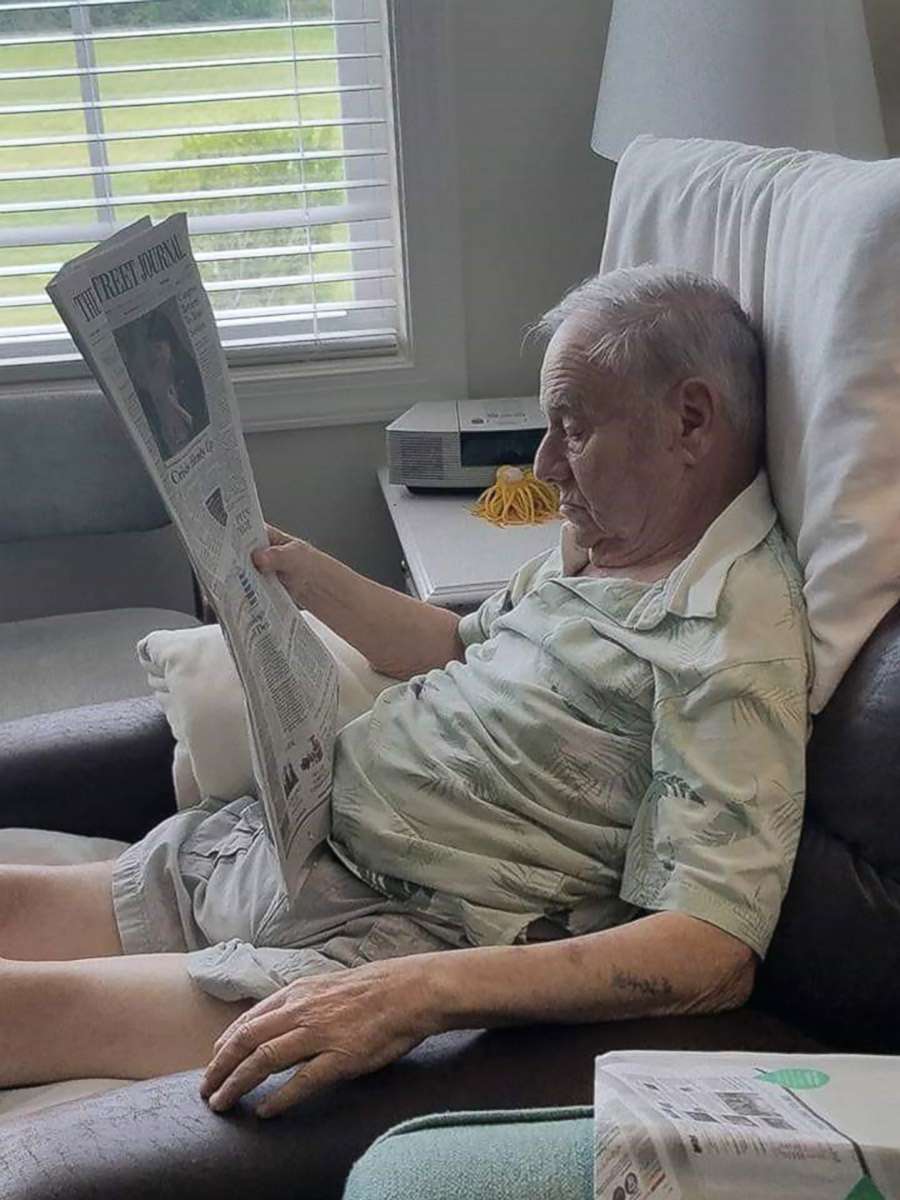

For Alex Spier, the symptoms became too much to continue with assisted living, where he managed to escape twice. But even after his family moved him to a dedicated memory care program in Florida, where he was given supplementary care and a private attendant, his condition progressed.

Doctors resorted to aggressive medications, including a variety of antipsychotic and antiseizure drugs, but the sedation they caused — side effects of their use — only seemed to worsen his agitation and delirium.

In a decision that at first divided the family, Greg Spier and a niece who lives in Colorado decided to try marijuana edibles. The last-ditch effort involved Greg Spier, along with a private assistant, feeding his dad granola bar marijuana edibles up to four times a day during his final three months.

“The only thing that seemed to give him any reprieve was the marijuana,” Greg Spier said, adding that it allowed his dad to sleep.

According to Dr. Brent Forester, chief of the division of geriatric psychiatry at McLean, the science of medical cannabis for dementia is far behind what families like the Spiers are already doing on their own. Alex Spier wasn’t his patient, but Forester was fascinated to learn about the family’s success with edibles last year.

Forester’s own research involves the synthetic THC drug dronabinol, an FDA-approved medicine for chemotherapy-related nausea and AIDS-associated weight loss, which can cost $400 to $1,500 without insurance coverage.

Forester and his colleagues have published promising study results after giving dronabinol to agitated and distressed dementia patients, and are currently recruiting for a larger multicenter trial funded by the National Institute on Aging.

It’s true that in teens and young adults, frequent marijuana use is associated with a lower IQ and an increased risk of psychiatric disorders. In adults who have been using it since adolescence, it has been found to erode memory and visuospatial skills.

But these negative impacts could be limited to young brains that are exposed to marijuana for extended periods, and they might not be true for people who begin in older age. When a team of German and Israeli researchers gave low doses of THC to old mice, for example, learning and memory improved to a level similar to young mice.

When these scientists examined the brain tissue, they found that the mice given the THC had more complex hippocampal connections. By contrast, THC worsened brain function in young mice.

More promising for Alzheimer’s disease, animal research has also shown that THC may increase the neurotransmitter acetylcholine, just like the FDA-approved dementia drug Aricept. THC also appears to slow the accumulation of amyloid beta plaques, the hallmark characteristic of Alzheimer’s.

Forester and his colleagues theorize that these protective effects — which result from the use of cannabinoid drugs — might reduce the risk of the abnormal behaviors associated with dementia. However, only time and research will tell.

The Spier Family Foundation is eager to support this work and is giving private dollars to fund it. Federal funding is difficult to obtain with marijuana still being classified as a schedule I controlled substance, defined as “having no currently accepted medical use and a high potential for abuse.”

There are currently no FDA-approved drugs that treat the behavioral symptoms of dementia, which can become the most distressing aspect of the condition. Current drugs that are given to Alzheimer’s patients, such as antipsychotics and benzodiazepines, can even make their symptoms worse due to side effects, Forester said.

“We really need to open up opportunities to study medical marijuana for this particular indication. I think there’s enough evidence from the synthetic THC as well as anecdotal reports that it’s certainly worth studying,” Forester said.

The Spier Family Foundation’s willingness to fund this work is extraordinarily important, Forester said, adding that he was hopeful the medical marijuana industry will see the value in supporting such research as well.

Dr. Ford Vox practices rehabilitation medicine at the Shepherd Center in Atlanta and contributes analysis to the ABC News Medical Unit.