Man cured of HIV, cancer following breakthrough stem cell transplant: Doctors

A 66-year-old man who was diagnosed with HIV in 1988 is said to be free of both the HIV virus and cancer, following a stem cell transplant from an unrelated donor for leukemia, according to a breakthrough announcement at the International AIDS Conference in Montreal, Canada.

The patient was treated at City of Hope, one of the largest cancer research and treatment organizations in the U.S. and one of the leading research centers for diabetes and other life-threatening illnesses, the organization said.

The City of Hope patient is reportedly the fourth patient in the world and the oldest to go into long-term remission of HIV without antiretroviral therapy (ART) for over a year after receiving stem cells from a donor with a rare genetic mutation.

"We were thrilled to let him know that his HIV is in remission and he no longer needs to take antiretroviral therapy that he had been on for over 30 years," Jana K. Dickter, an associate clinical professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases at City of Hope who presented the data, said in a press release.

According to City of Hope, the patient received a chemotherapy-based, reduced-intensity transplant regimen prior to his stem cell transplant. "Reduced-intensity chemotherapy makes the transplant more tolerable for older patients and reduces the potential for transplant-related complications from the procedure," the organization said in the release.

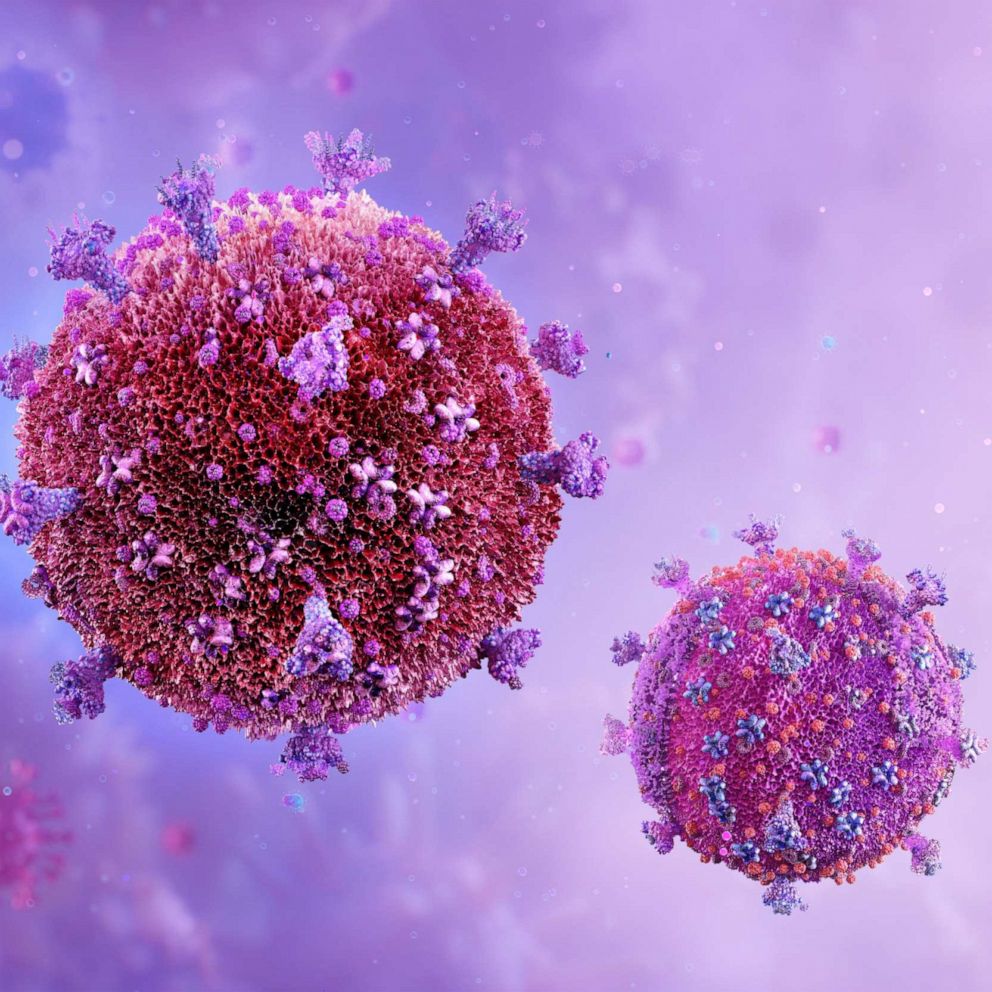

The patient received a blood stem cell transplant at City of Hope in early 2019 for acute myelogenous leukemia from an unrelated donor who has a rare genetic mutation, homozygous CCR5 Delta 32, City of Hope said. That mutation makes people who have it resistant to acquiring certain strains of HIV.

CCR5 is a receptor on CD4+ immune cells, and HIV uses that receptor to enter and attack the immune system. But the CCR5 mutation blocks that pathway, which stops HIV from entering the cells and therefore replicating.

The City of Hope patient has not shown any evidence of having replicating HIV virus since the transplant, the organization said.

"We are proud to have played a part in helping the City of Hope patient reach remission for both HIV and leukemia. It is humbling to know that our pioneering science in bone marrow and stem cell transplants, along with our pursuit of the best precision medicine in cancer, has helped transform this patient’s life," said Robert Stone, the president and CEO of City of Hope, in a statement.

While the announcement provides hope for millions living with HIV, medical experts have cautioned that a procedure like this is not a viable cure for the virus.

Dr. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, urged caution in February after researchers announced that an American woman had been cured of HIV after undergoing a new transplant procedure using donated umbilical cord blood.

"It is not practical to think that this is something that's going to be widely available," Fauci said. "It's more of a proof of concept."

Because bone marrow transplantation is a dangerous and risky procedure, it is considered unethical to perform it on people with HIV, unless the person also has cancer and needs a transplant as part of their cancer treatment.

Despite the fact that this is not a practical and applicable cure for HIV on a large scale, there have been incredible strides in HIV treatment and innovation over the years that allow individuals living with HIV to live a normal and healthy life.

Known as U=U, or Undetectable=Untransmittable, if an HIV-positive person begins appropriate HIV treatment, takes it daily and brings the virus in their body to an undetectable level, the individual cannot transmit the virus to someone as long as their virus levels remain undetectable on said treatment or medication.

In December 2021, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first long-acting injectable drug for HIV prevention.

Until this, the only medications licensed and approved by the FDA for HIV prevention or pre-exposure prophylaxis, most commonly known as PrEP, were daily pills, which prevent HIV from entering the cells in the body and therefore prevent infection. When taken as prescribed, PrEP services reduce the risk of getting HIV from sex by about 99%, according to new data from the CDC.

A less reliable, though still highly effective, way of preventing HIV infection is post-exposure prophylaxis or PEP. These pills are meant to be taken right away or within 72 hours if someone has been exposed or potentially exposed to HIV to try and prevent the virus from entering immune cells causing infection. It's like an emergency pill for HIV prevention and must be taken daily for 28 days.

Now, individuals who feel at-risk of HIV infection have the option of taking the daily pill, or the new shot every two months, after two initiation injections administered one month apart.

On the vaccine front, Moderna recently announced that it's launched early stage clinical trials of an HIV mRNA vaccine. ABC News previously reported that the biotechnology company teamed up with the nonprofit International AIDS Vaccine Initiative to develop the shot, which uses the same technology as Moderna's successful COVID-19 vaccine.

ABC News' Eric Strauss, Sony Salzman and Jennifer Watts contributed to this report.