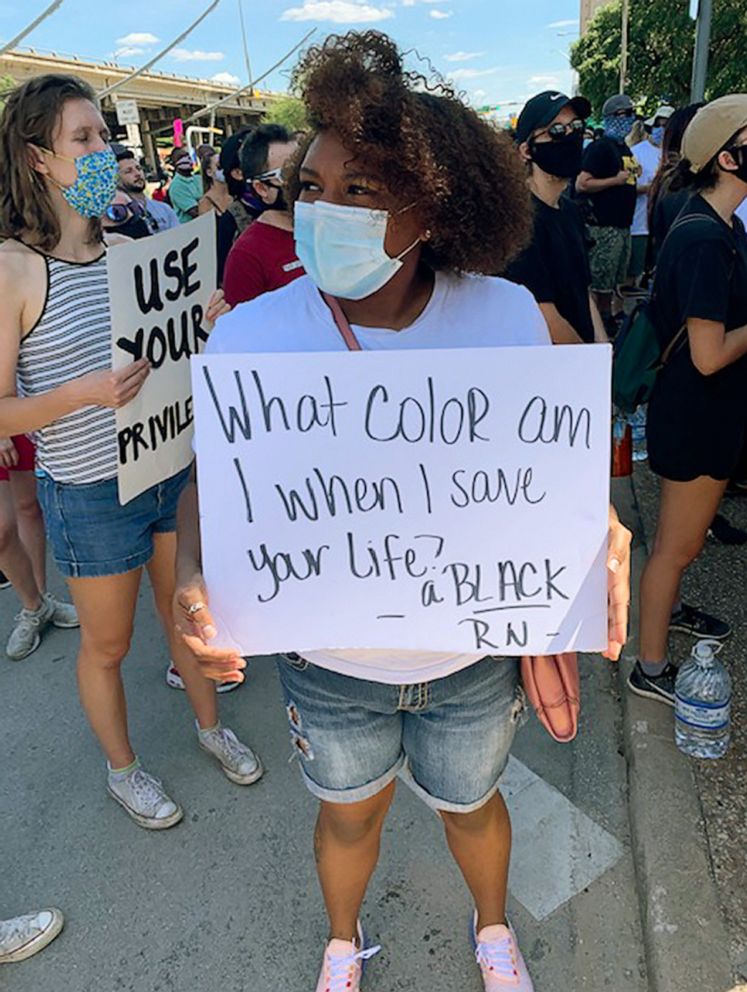

Exhausted health care workers join Floyd rallies to protest disparities

Medical professionals across the country are going straight from their hospital shifts to demonstrations, offering aid to those injured outside city halls and police stations as ugly scuffles between law enforcement, civil rights advocates and looters continue over the death of George Floyd.

"Our nurses heard the clarion call on their own," Dr. Millicent Gorham, National Black Nurses Association's executive director, said. "That there needs to be a call to action by everybody. The violence against black men and people of color is nothing new, but our members have decided enough is enough. We're going to offer our services and support to Americans exercising their rights."

Anna Maria Ruiz is one of several nurses who joined thousands of Texans protesting in Austin Sunday, just before heading in for a long graveyard shift at North Austin Medical Center. After the peaceful protest took an unexpected violent turn, she jumped into action to address rubber bullet wounds and pepper spray afflictions among her fellow protesters.

"We take an oath to preserve life as best we can and stop preventable deaths," Ruiz said. "In this situation, it's too important not to tackle outside of the hospital."

Dr. Gigi Chawla is a pediatrician at Children's Minnesota in Minneapolis. She helped clean up her city last weekend after multiple buildings in the community burned down, before heading to a protest with hundreds of others outside a police precinct. The peaceful protest remained true to its name, but Chawla was ready to offer medical assistance to police officers and activists alike without hesitation.

"That's my duty," Chawla said. "I offer health care support to anyone in need, unexpected or not."

Children's Minnesota is one of several health systems in the Twin Cities honoring George Floyd's memory.

Dr. Julius Johnson is a nurse practitioner and president of the Greater New York City Black Nurses Association. He walked with thousands of others from Harlem to Brooklyn Monday and is organizing a march led by medical workers beginning in Union Square this Sunday, where he expects at least 50 other health care workers to join him.

"We're black before we're any kind of professional, and we have to stand up for our community," Johnson said. "We want to show that there are professionals that are protesting, we don't have the privilege of staying home during the coronavirus pandemic. We will absolutely be offering our medical services to our fellow protesters."

But it's not just medical services Johnson hopes to offer. He says he's on a mission to protect his community from looters as well.

"I understand why people are frustrated, especially in this city where most people are out of work and a $1,200 check doesn't even cover your rent," Johnson said. "But looting is unacceptable and solves nothing. I won't allow it to happen in my presence. It detracts from our cause."

The organized march among health care professionals comes on the heels of a larger movement within the medical community condemning the killing of George Floyd while in police custody. National Nurses United -- an organization of registered nurses throughout the country-- released a statement demanding "justice for George Floyd and a stop to the unnecessary death of black men at the hands of those who should protect them."

The American Hospital Association called the death of George Floyd and others, "a tragic reminder to all Americans of the inequalities in our nation" and claimed "America's hospitals and health systems condemn racism of any kind," in addition to recognizing the need for "addressing health care disparities."

Racial disparities in health care on display during COVID-19 pandemic

A myriad of studies have found that black and white Americans receive different treatment options within America's health care system, even when factors like identical symptoms and similar insurance plans are at play.

The American Heart Association has repeatedly concluded white patients are far more likely to qualify for various heart surgery procedures and treatments than their black counterparts when exhibiting comparable symptoms. A study by the National Academy of Medicine gathered "race and ethnicity remain significant predictors of the quality of health care received" during patient diagnosis and Stanford University found black patients health outcomes improve considerably when treated by black doctors.

"I may have the same level of education and insurance a white male has, but that does not guarantee I will receive the same care and diagnostic tests in the emergency room," Dr. Marsha Dawson, National Black Nurses Association president, said. "That needs to change."

The Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported the COVID-19 death rate is notably higher among people of color, not to mention the fact that African Americans in coronavirus hot spots are twice as likely to die from the illness than their white counterparts.

It's a heartbreaking reality Art Gianelli, president of Mount Sinai Morningside, and his colleagues at Mount Sinai Health System in New York City know too well.

"We all saw first hand when black and brown patients came into our emergency departments, they came in sicker and were more apt to die from the virus," Gianelli said. "Our staff continues to see and feel it. But we don't have the tools right now to change that. These are long-standing issues with health care disparities that need to be addressed and not the virus itself."

Gianelli explained the significant number of lives lost at Mount Sinai hospitals contributed to a system-wide show of support for protesters Tuesday, with scrub-clad doctors and nurses holding a moment of silence to honor George Floyd before cheering on fellow New Yorkers protesting as they passed medical facilities throughout the city. It's a nod to those demanding action against decades of racial injustice-- an idea Gianelli says pulls on the very heartstrings of health care.

"Our roots are in caring for people who are discriminated against so in many ways, this was getting at the core values of this health system," Gianelli said. "Honoring George Floyd's memory with peaceful protesters is something many of us at Mt. Sinai are committed to."

That commitment appears to ring true for thousands of American healthcare workers and civilians too, perhaps characterized best by Johnson's answer to a police officer who asked why he's marching.

"I handed her a list of recommendations that we have," Johnson explained. "Yes, George Floyd died, and yes, the way it happened is common practice. We've seen the same type of incidents here in New York. We want more diversity among psychiatrists that do evaluations of officers before they are hired. More transparency from the Civilian Complaint Review Board. But mostly, we simply want the police to stop brutalizing us."