Laboratory-grown lungs simulate coronavirus infection

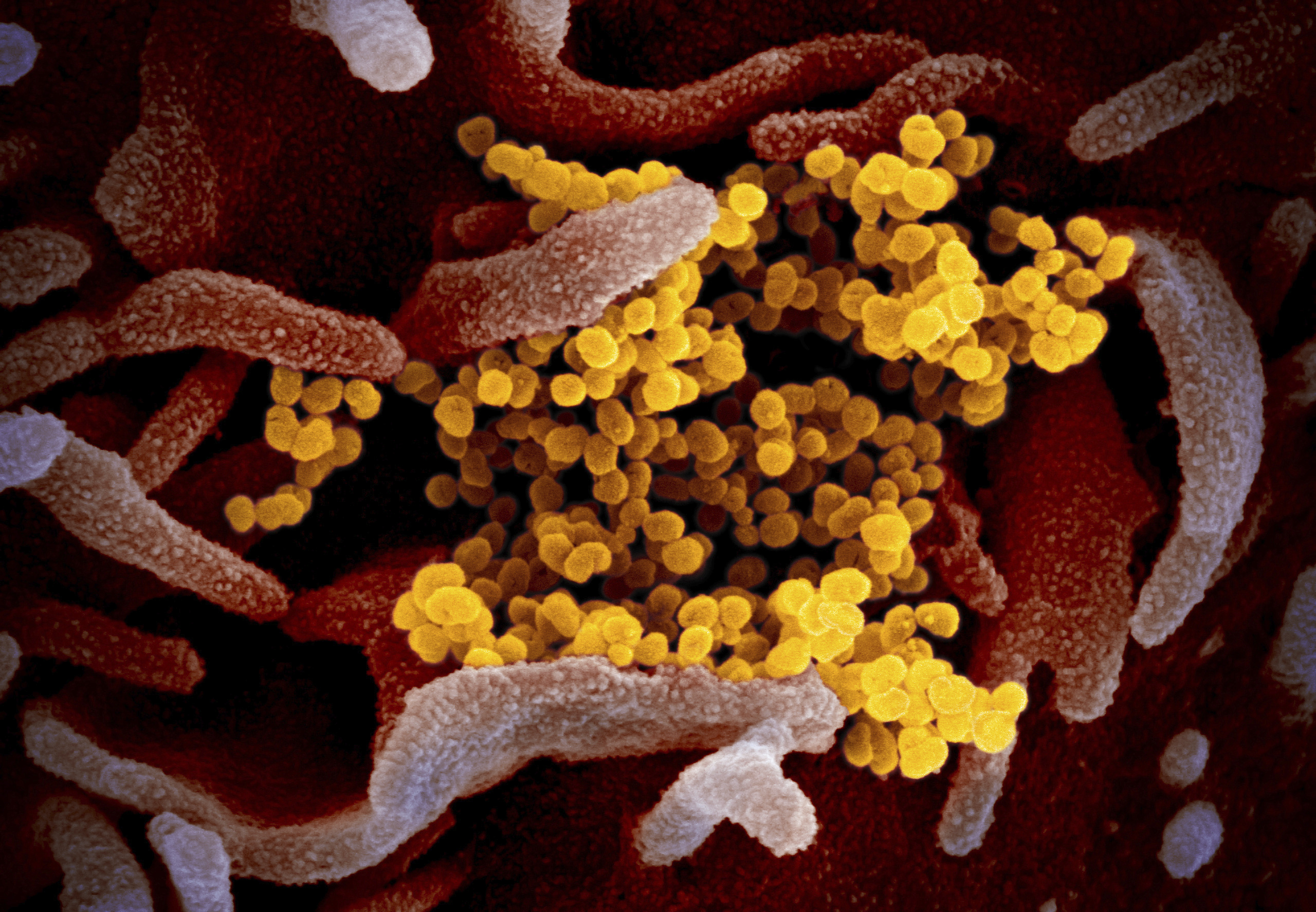

Previous reports have suggested that the lungs are the part of the respiratory system most severely impacted by COVID-19 infection. In Boston, scientists at the National Emerging Infectious Disease Laboratory have artificially created a lab-grown replica of the air passages and air sacs within the lung to investigate how COVID-19 infection wreaks havoc on the body.

The laboratory-grown lung models help scientists observe and learn how coronavirus attacks lung tissue without having to dissect or biopsy the lungs of people who have been sick with COVID-19.

According to Adam Hume, senior research scientist at NEIDL, "With this model, we are able to get a better idea of what is going on in the lungs, which are the primary targets of infection."

Hume said lab-grown organoids -- groups of cells that mimic structures within organs -- are an especially effective experimental model because of how similar they are to the actual cells in the human body.

To make lung organiods, Hume and his colleagues have collaborated with researchers at the Center for Regenerative Medicine in Boston, which has artificially engineered other organs, such as intestines and brains.

These organoids are carefully transported to NEIDL where researchers infect the tissue with coronavirus. Because the virus can be deadly, they conduct these experiments wearing a fully encapsulated suit with an air supply hose and three pairs of gloves.

With this scientific technique, Hume and his colleagues hope to evaluate how quickly the virus multiplies within the lung cells and how the cells respond to this infection to determine why certain patients develop such severe symptoms.

Although some patients will recover quickly from COVID-19, others will become extremely sick, requiring breathing assistance and possibly mechanical ventilation. Scientists still do not understand exactly what makes someone susceptible to severe disease -- but Hume is hoping these experiments will help.

"Right now, this is just a model system for looking at infection in the lungs," said Hume. "Next steps are to take these pathways and look at whether there are specific drugs that could target cellular pathways that might be important for virus replication."

Stephanie E. Farber, M.D. is currently completing her final year of plastic surgery residency at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and is a medical contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit.