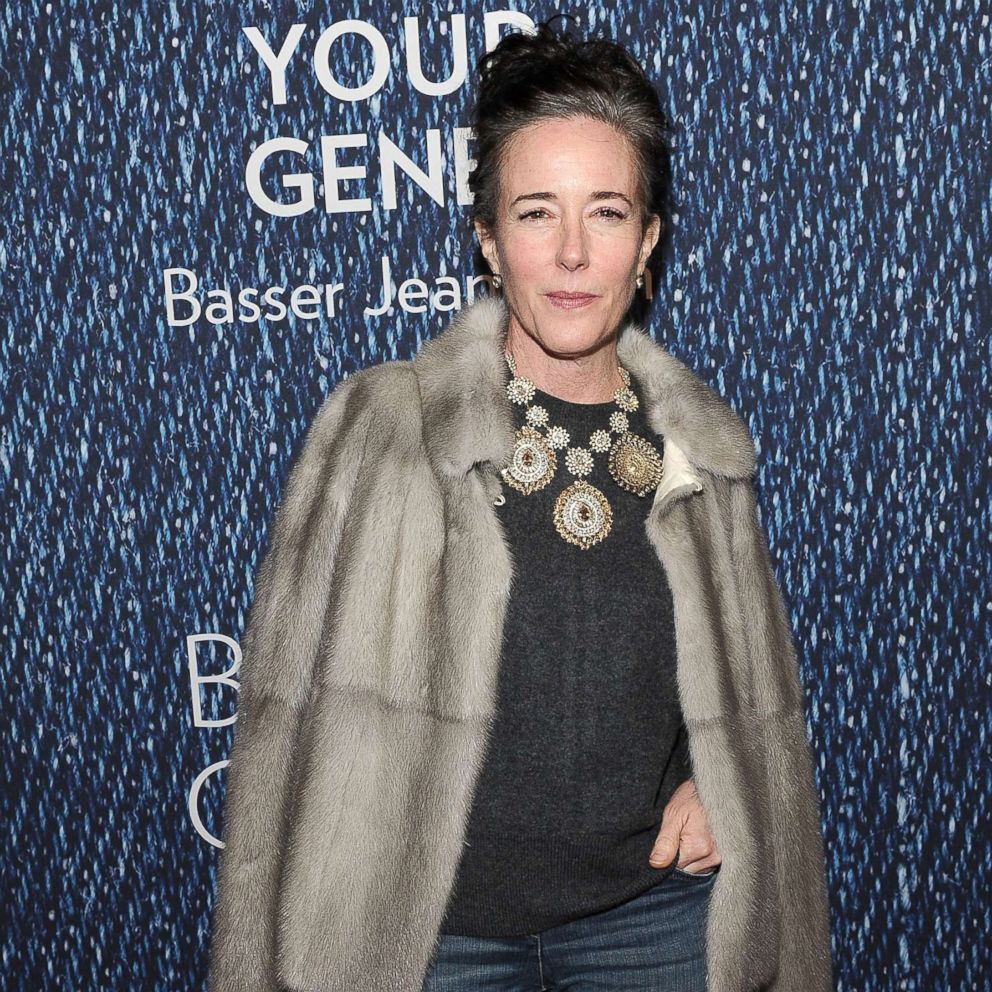

Kate Spade 'sounded happy' before her suicide: How depression can be so hidden and what loved ones can do

The night before Kate Spade took her own life in her Manhattan apartment, she "sounded happy," according to her husband.

Her brother said Spade had very recently been talking about the future.

Spade’s friend, celebrity stylist Joe Zee, said he and other friends were in "shock" that the 55-year-old designer known for her eclectic style and whimsical designs had taken her own life.

"I think the Kate that we knew was incredibly spirited and jovial and I think this is just a hard time," Zee said on "GMA" Wednesday, the day after Spade’s suicide. "It's hard for me to speculate what happened at home behind closed doors, but the Kate that really I knew was always with a smile."

Spade's husband, Andy Spade, said in a statement to ABC News that his wife had been suffering from anxiety and depression for more than five years. He said her death was still "a complete shock."

What goes on behind closed doors for people with depression is very often different from what friends and even close family members see, experts say.

"Once you are struggling with depression and feel that admitting it would be a kind of defeat, you become invested in concealing it," said Dr. Jonathan Rottenberg, director of the University of South Florida Mood and Emotion Lab. "The longer that goes on, the more difficult it becomes to reverse and take off the mask."

Rottenberg, who did not treat Spade, continued, "In addition to the symptoms and burden of depression, there’s an additional burden of trying to shield others from that."

Spade described her own life as "a little kooky but a lot of fun" in an interview with The Cut just two years before her death.

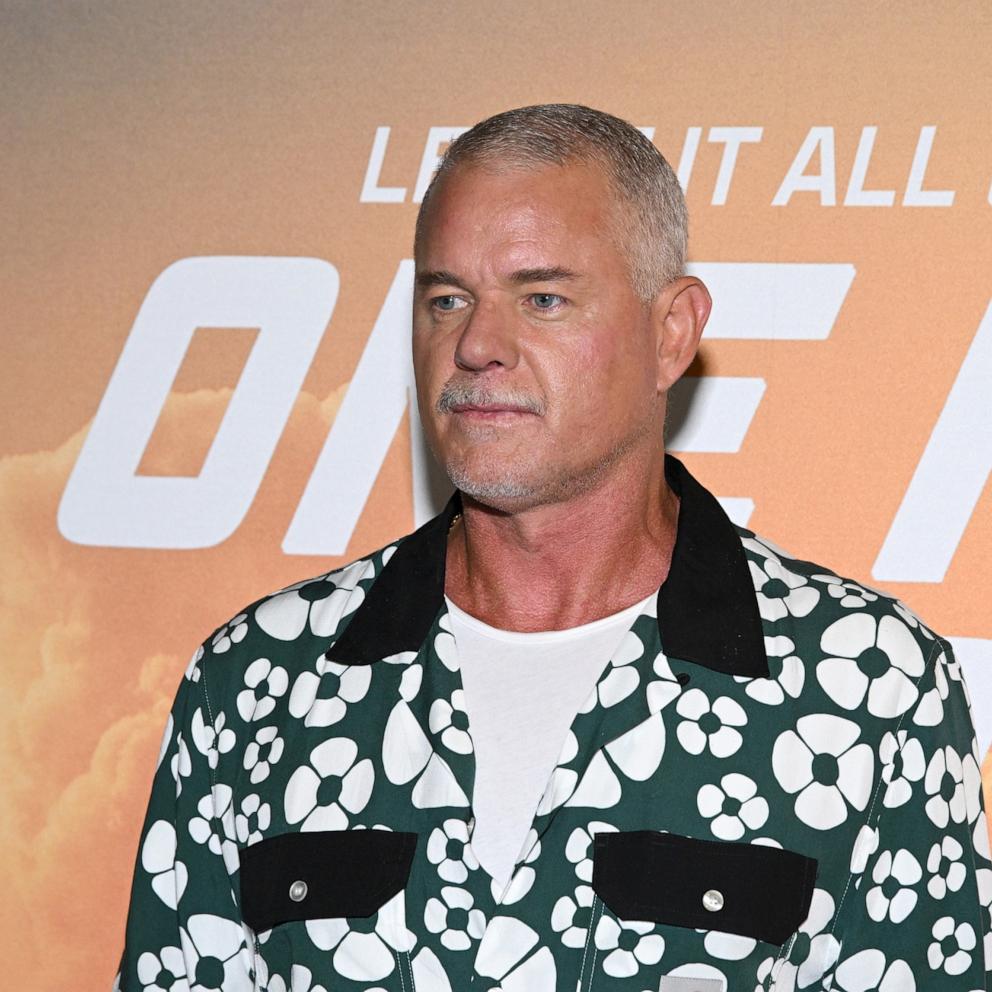

ABC News' chief meteorologist Ginger Zee, who first experienced depression right after college, said she was able to appear on TV even during her worst bouts of depression.

"It was Ginger Zee, the passionate female scientist who had a kick-ass job on TV, then I would go home and I would shirk into Ginger Zuidgeest, the introverted, depressed, drinking a bottle of wine a day Ginger that isolated herself to the point of hurting family and friends," said Zee, who wrote about her depression in her memoir, "Natural Disaster."

People with depression who start concealing their struggle from friends and loved ones can find it hard to reveal themselves, according to Rottenberg.

"Some people feel that others will think less of them if they admit that they’re struggling with depression or they think depression is just inconsistent with who they are," he said. "They hope it will be temporary and in the meantime don’t they share."

Rottenberg continued, "People become invested in concealing it and it is very hard to change that once you’ve been going on for weeks or months with the kind of charade that everything is okay."

A person with depression can go into "survival mode," according to Dr. Dan Reidenberg, executive director of Suicide Awareness Voices of Education (SAVE), as they work so hard to conceal their struggle.

"It happens gradually and their mind and their body start focusing just on how can I get through the day," he said. "They’re still functioning and doing it, but that’s all they're focusing on."

Struggling in silence, of course, adds to the difficulties faced by family members and friends of people with depression.

"When it’s severe, depression does take time to resolve," Rottenberg said. "It puts loved ones in a challenging situation because it’s sort of, in a sense, they too have to endure the depression."

Know a person struggling?

Suicide is the 10th leading cause of death in the United States, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Nearly 45,000 lives were lost due to suicide in 2016, according to CDC data. More than half of people studied by the CDC who died by suicide did not have a mental health condition.

"My message to family and friends is the person who you’re worried about doesn’t have to die at their own hands," Reidenberg said. "There are things that can be done. We can’t prevent every single suicide, but the majority we can."

Signs to look for

Significant changes in behavior are a major warning sign a person, especially one with depression, may be slipping into suicide, according to Reidenberg.

If someone with depression is acting out of character, that is a time to ask more questions, get others involved and take more actions, he explained.

Other changes in behavior that may be red flags are withdrawal from family, friends, work and social activities, a change in activity level, increased anxiety, which can be restlessness or agitation, and a lack of sleep.

"Look and listen for warning signs because it is not as if just one morning someone wakes up and says, 'Today is the day I’m going to do this,'" Reidenberg said. "It happens over time and falls on a continuum."

How to help

The most important thing loved ones can do is to be available, according to both Reidenberg and Rottenberg.

Being available can mean being there to listen, without judgment, and to check-in continually to say something as simple as, "'Hi, how are you doing? I'm available and around,'" explained Reidenberg.

"Reassure them that they are important to you, you want them to be around and want them to be well," he said. "The reassurance that people care by statements and words mean a lot to someone who emotionally is drained from the depression."

Keeping a schedule of eating three times a day and waking and sleeping at the same time each day for structure can be important for people with depression, according to Reidenberg.

Finally, be willing to move past the stigma of speaking about depression and ask the person direct questions.

"If you care about someone, it’s really important to ask, ‘What are you doing about this? Are you talking to someone? Have you tried medication?'" Reidenberg said, adding that checking in on those three questions later is also important.

What not to do

Don't rush in and try to offer advice and a fast solution to someone with depression, advises Rottenberg.

"People say things that are unintentional. They offer advice or say the person has a great life and shouldn't feel sad," he explained. "What the person wants most typically is just to be heard and understood and cared for."

"A listening ear goes a long way," he added, "listening and signaling that you love the person and, regardless of what they’re struggling with, you're invested in them and you’re not going to leave them."

If you are in crisis or know someone in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741. You can reach Trans Lifeline at 877-565-8860 (U.S.) or 877-330-6366 (Canada) and The Trevor Project at 866-488-7386.