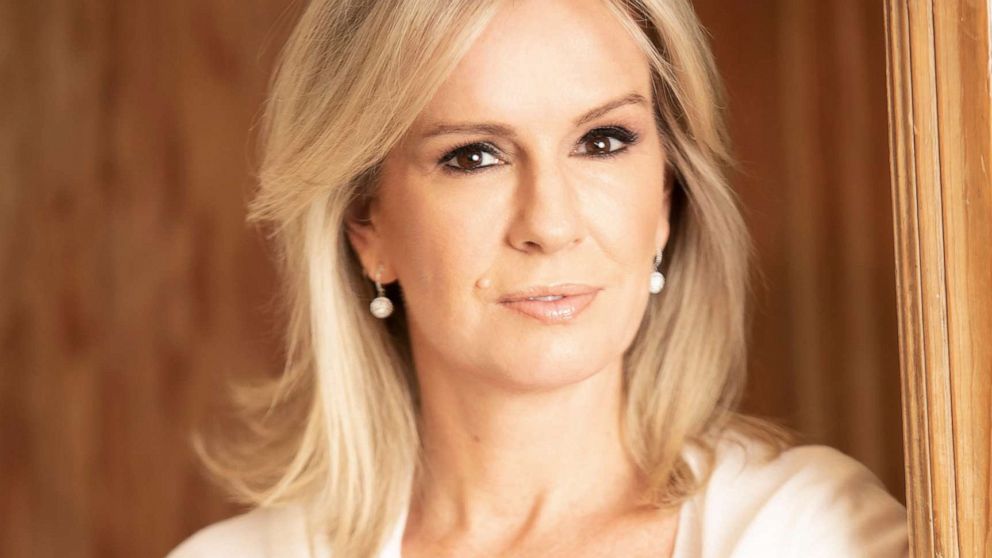

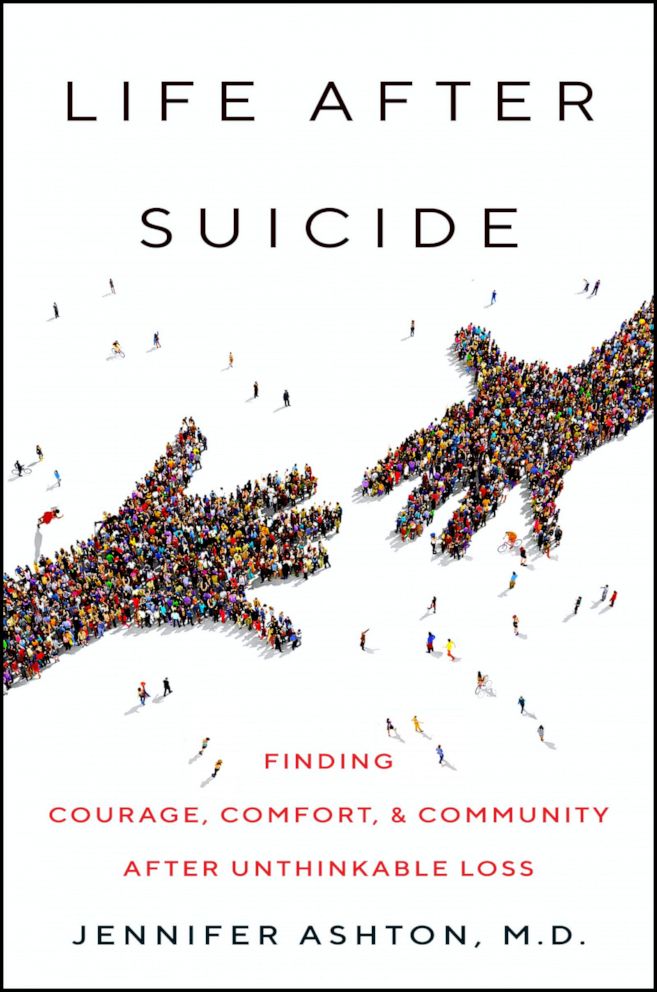

From hurt to healing: Read an excerpt of Dr. Jennifer Ashton’s ‘Life After Suicide’

Dr. Jennifer Ashton, ABC News’ chief medical correspondent, has released her book, titled "Life After Suicide: Finding Courage, Comfort & Community After Unthinkable Loss." In it, she shares her emotional journey of coping with the death of her ex-husband Rob, who died by suicide. Within the book, she shares how she found the strength to be there for her children and heal after their tragic loss, and offers a rare look at how survivors can learn to cope with the grief that comes with tragically losing a loved one.

You can read excerpts from “Life After Suicide” below.

Suicide. Rob died by suicide. I couldn’t begin to wrap my head around it. That gentle man, deliberately doing something so violent, and terrifying, and isolated—what could possibly have pushed him to be so resolved to end his life that it overrode the most basic human instinct of survival? His love for our children was soul-deep. Endless. Incalculable. The pain that drove him over that bridge must have been massive to have overshadowed all that love, so massive that it couldn’t reach him, couldn’t make him stop and say, “I can’t do this to them.”

The divorce? Was that what caused him such massive pain? It couldn’t be. He seemed fine with it. He seemed to not even care all that much. I was sitting right there, I heard him with my own ears tell Dr. Simring, when she asked us if we were having any thoughts of suicide, “No. Absolutely not.” Was he lying to her? Or had something happened to make him change his mind?

We’d never know, would we, because the only person who could tell us, and answer the countless other questions that were bound to come up, wasn’t here anymore, would never be here again. How was that possible?

Was he at least at peace now? Was that how this worked? I hoped so.

Was it really that same morning that I’d been at Soul-Cycle, preoccupied with what my life was going to look like after our divorce, and how divorce was the worst thing that ever happened to me, and finding my way through feeling like a failure to regain my optimism? It seemed like a lifetime ago. I felt like a failure that morning? Really? Multiply it by about a million. . . .

“You can’t let this destroy you.”

“Oh, my God, Mommy, please don’t leave me.”

My children’s father was gone. My children had lost their daddy. Suddenly I was the only parent they had. It made me unbearably sad, and unbearably frightened.

I’d never been one of those people who gave a lot of thought to death. I got it that it was inevitable, and I wasn’t especially looking forward to it; but it wasn’t something I thought about very often, certainly not anything I would have called an active fear. Now, out of nowhere, the fear of dying and leaving my children with no parent at all slammed into me. I couldn’t let that happen. If it took becoming the most cautious person on this planet, if it took never riding in the back of a cab without my seat belt again, and certainly if it took giving up scuba diving—whatever it took, however much or little I had to say about it, Alex and Chloe would not become orphans. Orphans? Oh, God, whose mind had taken over and even let in that terrible word? Whose hell was I suddenly living?

Starting that night, and for weeks to come, I don’t think I ever slept for more than two hours at a time. I couldn’t sleep. I couldn’t eat. I couldn’t recognize myself, and the life I knew, in all this darkness. Maybe it was because, as of twelve short hours before, I wasn’t whole anymore. Maybe it was because, twelve short hours before, I completely shattered.

*****

“What the hell is wrong with me?” I asked her, in tears.

“Nothing,” she said. “What you’re going through is a normal part of healing—it’s not just normal, it’s healthy. It’s called ‘multiple truths.’ ”

“Multiple truths” means that you can feel opposite ends of the emotional spectrum at the same time without one of those feelings negating the validity of the other. You can be in the worst, most gut-wrenching grief and still laugh, or feel something positive, or even fall in love, and it doesn’t diminish the depth and sincerity of your grief. As Dr. Simring emphasized, it’s not choosing grief or laughter, it’s accepting and not judging the fact that grief and laughtercan and do coexist—“multiple truths,” both of them real and perfectly appropriate; so essentially, don’t beat yourself up about them, embrace them as a sign that you’re making progress.

It was a breakthrough for me, and a big relief. I realized I’d been trying to push away any feelings of happiness and hopefulness, thinking they were disrespectful to Rob’s memory. But would Rob really have wanted to leave our children and me a legacy of misery for the rest of our lives? Of course not. That’s not who he was. And ready or not, looking forward was an inescapable part of my reality, with moving day, May 1, getting closer and closer.

I’ve always loved moving. I know to some people that’s like saying I’ve always loved root canals. But it’s like a new beginning to me, a new phase, a clean slate; and I also love the whole nesting and organizing facets of turning a blank, empty space into a warm, comfortable, welcoming home.

There was no question that our move from Fort Lee into an apartment in New York City was emotionally essential for my kids, and in some ways for me as well. I was excited about it because they were excited about it. I appreciated the busyness of it, and the chance to tackle a big challenge I happen to be good at. And all of us were beyond ready to escape our relentless view of the George Washington Bridge.

For the first time in my life, packing and moving brought a bittersweet sense of heaviness with them. Rob had already moved out of that apartment and into his own place many months earlier, when we first separated. But he’d also lived in that apartment for a year, back when we were still married and trying to make things work; and as I stared at stacks of boxes, I was surprised to feel such a tangible connection to him, a connection I hadn’t felt during our divorce. I’d reach to open the refrigerator door, for example, and find myself thinking, “Rob touched this handle,” or glance over at the bathroom sink and be almost amazed that once upon a time, Rob stood there shaving. It felt like even more of a good-bye that our new apartment on the west side would be the first place I’d lived in twenty-two years that Rob would never come walking into, or even see. The finality stopped me in my tracks more than once as I tried to wrap my head around the idea that “never” really did mean never…

The new apartment was unpacked, organized, feng shui’d, and ready by the time Alex and Chloe got back from school. They loved it the instant they walked through the door, and I loved knowing I’d given my kids a home they’d look forward to instead of dreading. I’d made sure to keep their father’s presence alive in our new home, with lots of happy photos of him with them, him with his best friends, and him with all of us on display. I’d put a lot of those photos away when Rob and I were going through our divorce—amicable or not, I don’t know too many people who enjoy looking at pictures of their soon-to-be-ex spouses everywhere they turn. But that seemed like ancient history now. He belonged here, smiling at us. I even put special effort into decorating the kitchen in his honor. Rob was a brilliant cook, and brilliant is not too strong a word. I, on the other hand, have to Google instructions on how to boil water. Rob would have appreciated a nice kitchen, so I made sure that our kids and I would have one whether I ever used it or not.

In fact, I put another finishing touch on the kitchen a few days ago, while writing this book. Rob and I had taken a wonderful trip to Florence, Italy, in 2006, for our tenth wedding anniversary. We were browsing one day in this lovely antique art store and came across the most charming little two-by-two-inch two-hundred-year-old paintings, one for each letter of the alphabet. We bought our initials, “R” and “J,” and also “A” and “C,” for Alex and Chloe. I wasn’t sure what I was going to do with the “R” during our separation. Giving that one to Rob seemed weird, so I just kept all four; and now all four letters are on our kitchen wall, artistically (more or less) arranged around the light switches. Dr. Simring promised us over and over againthat, with enough time and enough healthy healing, the day would come when our memories of Rob would make us smile rather than cause us pain. A year and a half later, those little antique initials in the kitchen make me smile.

From LIFE AFTER SUICIDE by Jennifer Ashton, M.D. Copyright © 2019 by Jennifer Ashton. Reprinted by permission of William Morrow, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

Proceeds from the sales of the book will be donated to Vibrant Emotional Health, which administers the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline and other programs related to crisis response and emotional well-being, and the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

If you or someone you know needs to talk, call 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

If a person says they are considering suicide:

"Life After Suicide: Finding Courage, Comfort & Community After Unthinkable Loss" is available on May 7.