Hospital charges thousands to man who fainted

This story is from Kaiser Health News

Matt Gleason had skipped getting a flu shot for more than a decade.

But after suffering a nasty bout of the virus last winter, he decided to get vaccinated at his Charlotte, N.C., workplace in October. “It was super easy and free,” said Gleason, 39, a sales operations analyst.

That is, until Gleason fainted five minutes after getting the shot. Though he came to quickly and had a history of fainting, his colleague called 911. And when the paramedics sat him up, he began vomiting. That symptom worried him enough to agree to go to the hospital in an ambulance.

He spent the next eight hours at a nearby hospital — mostly in the emergency room waiting area. He had one consult with a doctor via teleconference as he was getting an electrocardiogram. He was feeling much better by the time he saw an in-person doctor, who ordered blood and urine tests and a chest-X-ray.

All the tests to rule out a heart attack or other serious condition were negative, and he was sent home at 10:30 p.m.

And then the bill came.

The Patient: Matt Gleason, who works for Flexential, an information technology firm in Charlotte. He is married with two children.

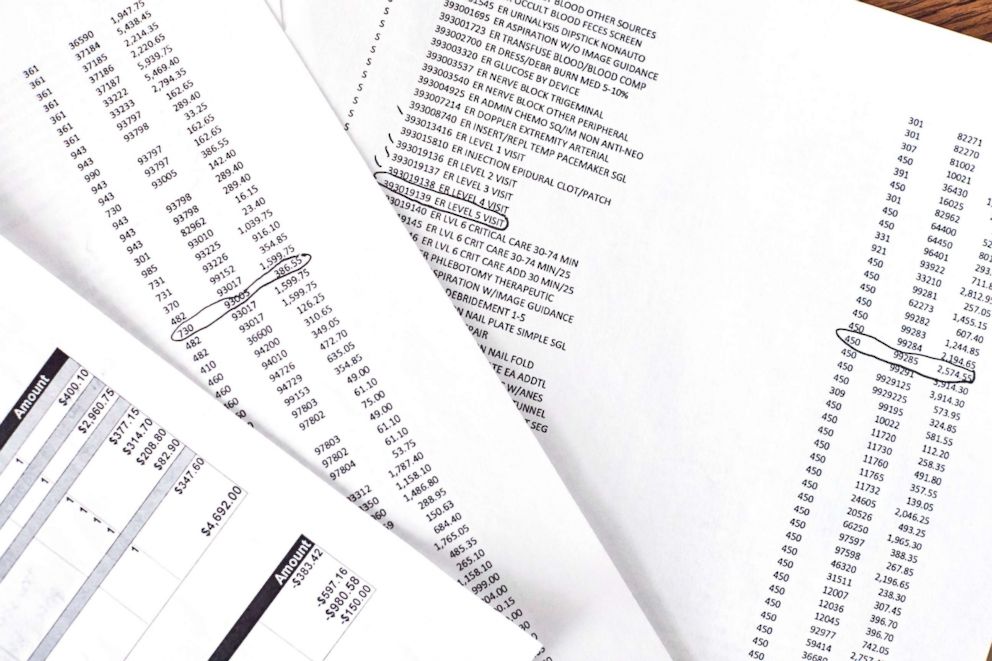

Total Bill: $4,692 for all the hospital care, including $2,961 for the ER admission fee, $400 for an EKG, $348 for a chest X-ray, $83 for a urinalysis and nearly $1,000 for various blood tests. Gleason’s insurer, Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina, negotiated discounts for the in-network hospital and reduced those costs to $3,711. Gleason is responsible for that entire amount because he had a $4,000 annual deductible. (The ambulance company and the ER doctor billed Gleason separately for their services, each about $1,300, but his out-of-pocket charge for each was $250 under his insurance.)

Service Provider: Atrium Health Pineville (formerly called Carolinas HealthCare System-Pineville), a 235-bed nonprofit hospital in Charlotte and one of more than 40 hospitals owned by Atrium.

Medical Service: On Oct. 4, Gleason was taken by ambulance to Atrium Health Pineville emergency room to be evaluated after briefly passing out and vomiting following a flu shot. He was given several tests, mostly to check for a heart attack.

What Gives: Fainting after getting the flu vaccine or other shots is a well-described phenomenon in the medical literature. But once 911 is summoned, you could be facing an ER work-up. And, in the U.S., that usually means big money.

The biggest part of Gleason’s bill — $2,961 — was the general ER fee. Atrium coded Gleason’s ER visit as a Level 5 — the second-highest and second-most expensive — on a 6-point scale. It is one step below the code for someone who has a gunshot wound or major injuries from a car accident. Gleason was told by the hospital that his admission was a Level 5 because he received at least three medical tests.

Gleason argued he should have paid a lower-level ER fee, considering his relatively mild symptoms and how he spent most of the eight hours in the ER waiting area.

The American Hospital Association, the American College of Emergency Physicians and other health groups devised criteria in 2000 to bring some uniformity to emergency room billing. The different levels reflect the varying amount of resources (equipment and supplies) the hospital uses for the particular ER level. Level 1 represents the lowest level of ER facility fees, while ER Level 6, or critical care, is the highest. Many hospitals have adopted the voluntary guidelines.

David McKenzie, reimbursement director at the American College of Emergency Physicians, said the guidelines were set up to help hospitals charge appropriately. Asked if hospitals have an incentive to perform extra tests to get patients to a higher-cost billing code, McKenzie said: “It’s not a perfect system. Hospitals have an incentive to do a CT exam, and taxi drivers have an incentive to take the long way home.”

The guidelines don’t determine the prices hospitals set for each ER level. Hospitals are free to set whatever prices they want as long as their system is consistent among patients, he said.

He said the multiple tests on Gleason suggest the hospital was worried he could be seriously ill. But he questioned why Gleason was told to stay in the ER waiting area for several hours if that was the case. It’s also not clear if Gleason’s history of fainting and overall good health were considered.

Blue Cross and Blue Shield of North Carolina said in a statement that the hospital “appears to have billed Gleason appropriately.” It noted the hospital reduced its costs by about $980 because of the insurer’s negotiated rates. But the insurer said it has no way to reduce the general ER admission fee.

“We work hard to negotiate discounts that reduce costs for our members, but costs are still far too high,” the insurer said. “This forces consumers to pay more out of pocket and drives up premiums.”

Gleason, in fighting his bill, actually got the hospital to send him its entire “chargemaster” price list for every code – a 250-page, double-sided document on paper. He was charged several hundred dollars more than the listed price for his Level 5 ER visit.

“In this specific example, the price of admission to the ER was more than $2,960. That was on top of more than $1,000 for the medical procedures actually performed. We won’t significantly bring down health care costs until we address the high prices like these,” BCBS-NC said in the statement.

John Hennessy, chief business development officer for WellRithms, a consulting firm that reviews bills for large employers, said the hospital charges are significantly higher than what Medicare pays in the Charlotte area, but those are the prices Gleason’s insurer has negotiated. “Seeing billed charges well in excess of what Medicare pays is nothing unusual,” Hennessy said.

He said the insurer likely agreed to the higher charges to make sure it had the large hospital system in its network. Atrium is the biggest health system in North Carolina.

He said the coding “makes sense” because it meets the guidelines — even if that meant a nearly $4,000 bill for Gleason.

“The hospital has every right to collect it, regardless if you or I think it’s a fair price,” he said.

Resolution: After Gleason appealed, Atrium Health reviewed the bill but didn’t make any changes. “I understand you may be frustrated with the cost of your visit; however, based on these findings, we are not able to make any adjustments to your account,” Josh Crawford, nurse manager for the hospital’s emergency department, wrote to Gleason on Nov. 15.

Atrium Health, in a statement to KHN and NPR, defended its care and charges as “appropriate.”

“The symptoms Mr. Gleason presented with could have been any number of things — some of them fatal,” the hospital said.

“Atrium Health has set criteria which determines at what level an [emergency department] visit is charged. In Mr. Gleason’s case, there were several variables that made this a Level 5 visit, including arriving by ambulance and three or more different departmental diagnostic tests.”

Gleason said the $3,700 hospital bill won’t bankrupt his family. “What it does is wipe out our savings,” he added.

The Takeaway: Gleason, understandably, said he’s reluctant to get a flu shot in the future. But that’s not the best response. It’s important to know that fainting is a known reaction to shots and some people seem particularly prone. It’s best to sit or lie down when you get the vaccine, and wait five to 10 minutes before jumping up and returning to business.

Be aware: If you — or someone else — calls 911 for a health emergency, you are very likely to be taken to the hospital. You probably won’t have a choice of which one. And a hospital trip may not even be needed, so think before you call: “How do I feel?”

The medical professional who administered the shot might have suggested that calling 911 wasn’t a smart or needed response for a known side effect of a vaccine injection in a young person.

The emergency room is the most expensive place to seek care.

In hindsight, Gleason might have gone to an urgent care facility or called his primary care doctor, who could have evaluated him and run some tests at much lower prices, if needed.

But employers, hospitals and doctors regularly tell patients if they need immediate care to go to the ER, and hospitals often tout short waiting times in their ERs.

With high deductibles becoming more common, consumers need to be aware that a single trip to the hospital, especially an ER, could cost them thousands of dollars — even for symptoms that turn out to be nothing serious.

Alex Olgin of WFAE and Elisabeth Rosenthal of Kaiser Health News contributed to the audio version of this story.

Do you have an exorbitant or baffling medical bill? Join the KHN and NPR Bill-of-the-Month Club and tell us about your experience.

Kaiser Health News is a nonprofit news service covering health issues. It is an editorially independent program of the Kaiser Family Foundation, which is not affiliated with Kaiser Permanente.