Holiday hangover? Here are tips to beat belly bloat

It's that time of year when many people are hoping a change in diet will help them lose a few pounds or beat back digestive problems.

It turns out that just eating healthy is not so simple when it comes to fixing a common problem, belly bloat.

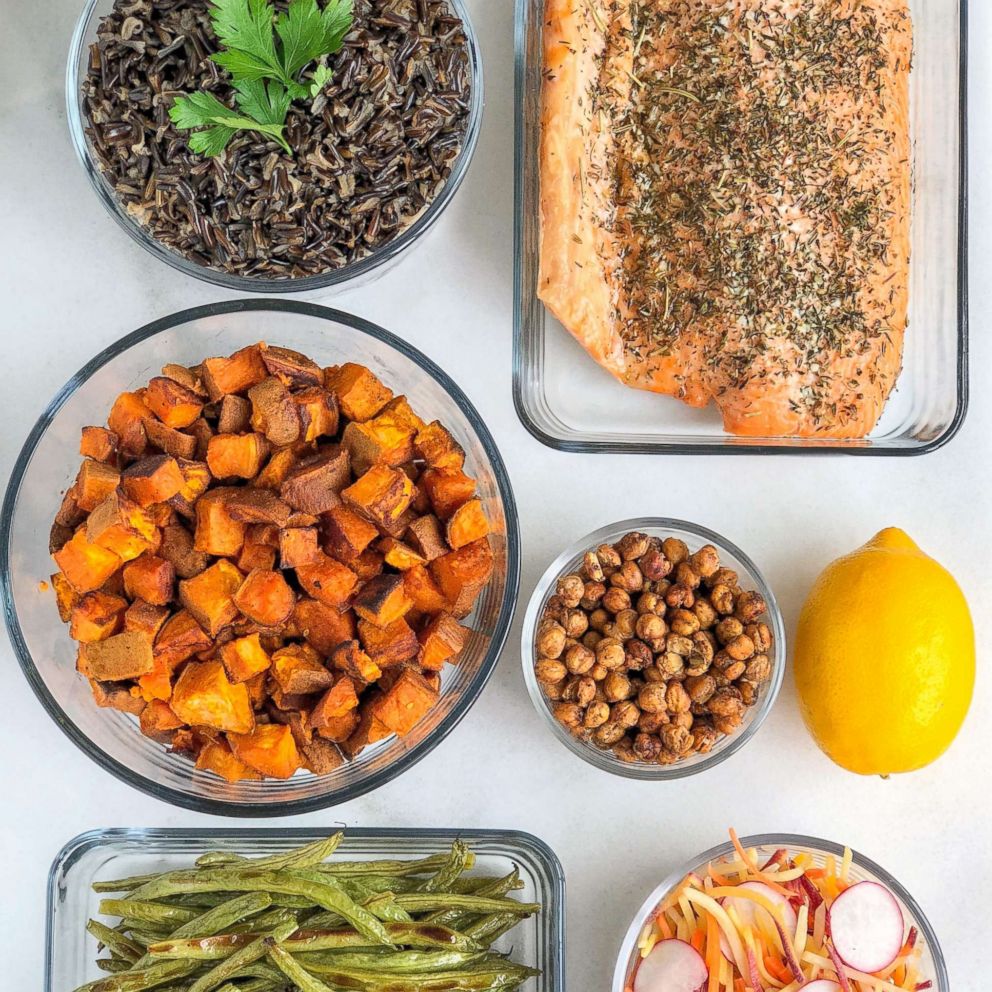

(MORE: How to meal prep like a boss in 2019)

Tamara Duker Freuman, a New York-based registered dietitian and the author of a new book, "The Bloated Belly Whisperer," says the key is listening to your own body.

"We all have different bodies, our digestive systems all work a little bit differently and not all objectively nutritious food will feel good in every person’s body," she said. "There are healthy foods out there that everyone can tolerate and your healthy food mission should be finding those foods, having that diet and not wondering or worrying what someone else is eating"

(MORE: All you need to meal prep, from a sample menu to a grocery list)

Read an excerpt below from Freuman's book.

The Sour Stomach Bloat: Classic Indigestion

WHILE SOME TYPES OF BLOATING feel more chronic in nature, other types are very situational.

Sour stomach bloating is one of those highly situational types of bloating; it’s typically provoked when susceptible people do one of a few things: Go too long in between meals without snacking, allowing themselves to become extremely hungry; Eat large-volume and/or high-fat meals; Drink alcohol, particularly on an empty stomach.

Often, my patients struggle to identify the trigger of their sour stomach bloating, because a particular meal may go over perfectly well one day but then provoke a bloating attack when eaten on another day. Understanding the situational context that triggers an attack is often the missing piece of the puzzle.

Classic indigestion

Indigestion isn’t a medical diagnosis but rather a description of uncomfortable symptoms you may experience after eating. Bloating is one of the common symptoms that falls under the indigestion umbrella; the others are described below.

Classic indigestion usually results from an underlying medical condition, such as gastritis (irritation of the stomach lining), ulcers, hiatal hernia, and/or acid reflux. Bloating that occurs in association with acid reflux or indigestion is what I’ve termed sour stomach bloating.

It’s this connection with acid-related problems that put the sour in sour stomach bloating and has led many marketers of antacid products to describe this type of bloating as acid indigestion. If there is no identifiable medical condition causing your indigestion-like symptoms, a doctor may diagnose you with functional dyspepsia (see chapter 5).

Indigestion is generally provoked by meals that are very large, high in fat, very spicy, and/or eaten too quickly. Drinking alcohol before such a meal may make you even more prone to experiencing indigestion.

What bloating from classic indigestion feels like

Bloating from classic indigestion comes on immediately after eating a meal. It is typically worse after a large or high-fat meal or any meal eaten after a prolonged period of fasting—such as if you skip breakfast and don’t eat your first bite until noon or after.

People describe it as feeling like their bellies swell up like a balloon full of air, and quite often it’s accompanied by belching. Sometimes the belching involves regurgitating small amounts of the contents of your stomach as well; most people recognize it as “throwing up a little in your mouth.” The bloating is very uncomfortable in a way that feels overfull. Your entire belly may be visibly distended, but more often, the discomfort is concentrated toward the top of the stomach, underneath the breastbone.

Bloating from classic indigestion is often accompanied by acid reflux, which can make itself known through heartburn, nausea, a sore throat, or a sour/metallic taste in the mouth. If you do have heartburn, then you may actually feel pain from this type of bloating rather than just discomfort and overfullness. In rare cases, you may vomit as well.

Diagnosing classic indigestion

“Indigestion” is not a clinical diagnosis in and of itself. Still, the symptoms are so predictable that most doctors know it when they see it.

Endoscopy (EGD)

Endoscopy is a test where a gastroenterologist sends a tube with a camera attached through your mouth, down the esophagus (food pipe) and into your stomach so s/he can see all of these organs from the inside. The test lasts only about 15 minutes, and it is done under sedation. Your doctor may use endoscopy to see whether you have irritation in the upper stomach region (gastritis), ulcers, or evidence of acid-related damage to your stomach or esophagus. S/he may also take tissue samples to see if you are infected with a bacteria called H. pylori that can trigger symptoms of indigestion.

Breath or stool testing for H. Pylori

Sometimes instead of going straight to endoscopy, doctors will order a quick and non-invasive test of your breath or stool to detect the presence of infection with H. pylori bacteria. If it’s positive, they may treat you with antibiotics and see how your symptoms respond before considering the relatively more invasive endoscopy. If H. pylori infection was the cause for your bloating and upper abdominal discomfort, the symptoms should resolve after antibiotic treatment. However, sometimes eradicating H. pylori actually makes acid reflux worse in the longer term. It’s a tricky dilemma to be sure, and in our practice, we don’t automatically go looking for H. pylori right out of the gates for precisely this reason. Instead, we often try diet modification and some basic over-the-counter remedies first before setting off in pursuit of this wily bacterium.

You’ll arrive fasted at a gastroenterologist’s office for your H. pylori breath test, and swallow a pill containing a compound called urea. During the test, which lasts only about 15 minutes, you’ll breathe into a tube so the technician can capture and analyze samples of the gases in your breath. If you’re infected with H. pylori, then your exhaled breath will contain all the clues needed to make the diagnosis. Blood testing for H. pylori has fallen out of favor because it can’t distinguish between an active infection and a past infection that has since been resolved.

Treating classic indigestion

Medical treatments

A variety of both over-the-counter and prescription medications are beneficial in managing bloating from indigestion.

Antacids

Antacid products are available over-the-counter, and they offer fast-acting but short-lived relief from sour stomach bloating. These products work by neutralizing stomach acid and helping to trigger belching, which can relieve some of the gas pressure that contributes to bloating. There are many options in the world of antacids. Chewable calcium carbonate tablets--like TUMS®, Rolaids® or Alka Seltzer® Heartburn Reliefchews®--are among the best-known options. (They also do double duty as a calcium supplement, which is great news for women who may be concerned about bone health.) If you’re a gum chewer who appreciates nostalgia, Chooz® antacid gum is a calcium carbonate gum that my patients of a certain generation swear by.

Liquid antacids containing magnesium hydroxide and/or aluminum hydroxide like Gaviscon®, Maalox® and Mylanta® are also effective; the latter two products also contain a gas bubble-busting ingredient called simethicone for added bloating relief. If you’ve got kidney disease, however, magnesium-based antacids may not be your best choice.

Sodium bicarbonate (otherwise known as baking soda) is also an effective buffer for stomach acid. You can concoct a homemade antacid by mixing baking soda with water, which is safe for adults but not young children. The proper ratio would be ¼ teaspoon of baking soda per cup of water. Alternatively, Alka Seltzer® tablets combine sodium bicarbonate with aspirin for mild pain relief. If you are allergic or sensitive to aspirin, or have a history of ulcers from using too many non-steroidal pain-relieving medications, this may not be the best choice for you.

Another common antacid ingredient called bismuth subsalicylate can multi-task by treating diarrhea in addition to the upper GI symptoms of indigestion; it is marketed as Pepto Bismol® or Kaopectate®. The active ingredient in these medications can turn your poop black, so don’t be alarmed if things look amiss in the toilet for a day or two after taking them. You should avoid these products if you’re allergic to aspirin.

H2 blockers

A class of medicines called H2 blockers interfere with histamine-stimulated stomach acid production; common drugs in this category are Pepcid® (famotidine) and Zantac® (ranitidine). While the antacids described above begin working within minutes, H2 blockers take about 30 minutes to kick in. However, they last far longer than antacids: up to 10 hours, instead of just an hour or so. These medications can be taken in advance to prevent symptoms in susceptible people—like at night before bed or in the morning before eating. Antacids can be taken at the same time as an H2 blocker to get immediate and long-lasting relief from indigestion: the antacid starts working immediately, and the H2 blocker starts working just as the antacid’s effects begin to fade.

Because H2 blockers have far fewer long-term side effects than another class of acid-suppressing medication called Proton Pump Inhibitors (PPIs), they are considered much safer for prolonged use, particularly for people who only experience occasional indigestion.

Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs)

If you suffer from chronic indigestion and have been diagnosed with acid reflux disease (GERD), your doctor might prescribe a type of medicine called a Proton Pump Inhibitor, or PPI for short. The generic names of all the drugs in the class end with the suffix “prazole.” (Brand names include Prilosec, Nexium, Prevacid, Aciphex and Protonix.) PPIs work by drastically reducing the amount of stomach acid you produce, to a far greater degree than H2 blockers. They are very effective at reducing the frequency and severity of sour stomach bloating episodes, but under the right circumstances (or wrong ones, depending on how you look at it), you may continue to experience breakthrough episodes. For example, even your PPI may be no match for a large, boozy steak dinner followed by cigars.

If you haven’t been diagnosed with GERD, then using a PPI to treat occasional sour stomach bloating would be like using a sledgehammer to swat a fly. Because these medications may be associated with more side effects than other types of acid-suppressing drugs, they would not be the ideal first-line treatment for sour stomach symptoms. PPIs also may be difficult to wean from once you start using them regularly; symptoms can get much worse for a period of time if you stop taking them cold turkey. Among other concerns, long-term use of PPIs may increase risk of osteoporosis, so it’s important to supplement calcium and Vitamin D if you are taking these meds for more than a few months. They may also pre-dispose you to developing a condition called Small Intestinal Bacterial Overgrowth (or SIBO; see Chapter 8.) These risks are generally deemed acceptable for people with GERD because they’re outweighed by an important benefit: a reduced risk of developing esophageal cancer from chronic acid damage. But these risks may be less appropriate for people without GERD, who could manage their bloating symptoms perfectly well with a well-timed TUMS® and some diet changes.

Dietary treatment for classic indigestion

Dietary changes work wonders for people with sour stomach bloating from classic indigestion.

If this is your brand of bloating, then an ounce of prevention can often spare you the need to rely on medication. The goal of your diet to prevent sour stomach bloat is to plan meals and snacks in a way that prevents your stomach from becoming either too empty or too full.

A too-full stomach can get you into trouble. Extra full bellies take a long time to empty, and predispose you to experiencing acid reflux during that prolonged emptying time. And if that large meal is also high in fat, it’s practically begging for the muscle separating your stomach and esophagus to loosen up and allow acid to reflux back up the food pipe, adding heartburn and pain to your already miserable bloating experience.But in my clinical experience, a too-empty stomach can be problematic, too. I’ve repeated this mantra to my patients thousands of times over the years: “an empty stomach is an acid stomach.” One of the surest ways to trigger a sour stomach bloating attack is to go way too long in between meals.

Once you finally eat, it’s common to experience a digestive overreaction no matter what you’ve eaten, and this can present itself as bloating, belching, over-fullness, sharp pains or a general feeling of having an unsettled stomach. If your meal of choice on an empty stomach happens also to be a large salad, it may provoke even more bloating and discomfort than a softer-textured meal that requires less time and less acid to break down.

Eat small meals or substantial snacks every 3 hours

The best way to prevent extremes in emptiness or fullness is to plan for a small meal or substantial snack every 3 to 4 hours. You should not go more than four hours without eating. In addition to keeping your belly calmer, eating frequently helps manage your hunger so that you’re less likely to overeat portions at the next meal. As best you are able, try to spread your intake as evenly as possible across the day’s meals and snacks so that the amount you eat at dinner is not particularly more food than what you ate at breakfast or lunch.

In order to achieve this, you’ll want to consider what qualifies as a “snack.” A lone banana between lunch and dinner may not be nearly enough to help manage your hunger levels—and therefore portions-- as you arrive at the dinner table. You’ll also want to be sure you’re not skimping on breakfast or lunch, as many of my patients are in the habit of doing. After all, if you ever arrive to a meal feeling famished from a too-light lunch or an absent breakfast, the likelihood of leaving that meal with a sour, bloated belly is high.

Finally, if you’ve gone more than 4 hours without eating, consider chewing a calcium carbonate antacid right before tucking into your next meal to help neutralize some of that stomach acid and minimize the likelihood of bloating after eating.

Watch out for big, fat and “tough” meals

Big, fat and tough may be great attributes for a bouncer, but they’re the worst possible qualities in a meal when you’re prone to sour stomach bloating. “Big” meals refer to large portions: overeating is a surefire way to provoke an attack of sour stomach bloating.

If you’re prone to overdoing it at meals, it’s important to eat regularly enough that you never arrive to the table feeling starving.

If restaurant meals are your Achilles’ heel, try asking for a take-out container to arrive along with your food so that you can pack up half the entrée before you start eating. Lastly, repeat after me: “Hara Hachi Bu.” This is the Japanese diet trick of eating just until you are 80% full. This technique allows your brain to catch up with your belly so that you don’t overeat before you’ve given your system enough time to register the feeling of fullness. It takes practice to master the art of stopping at 80% fullness, but keeping this goal at the forefront of mind as you sit down to eat will likely slow you down and reduce the likelihood of overdoing it.

Fatty meals are a well-known cause of acid reflux, and they can trigger the sour stomach bloating that often accompanies it. Greasy take-out food, pizza with extra cheese, cheeseburgers with fries, pasta bathing in cream sauce, fried foods and BBQ ribs are some of the high-fat staples of an American diet that are likely to provoke an attack of sour stomach bloating.

I’m not suggesting that all high fat foods need to be off limits if you’re prone to sour stomach bloating. But what I do recommend is that you consume them as a “garnish” to an otherwise lower fat meal. Eating a slice of cheese on a turkey sandwich is quite different than eating an appetizer serving of deep fried mozzarella sticks. Having a few slices of bacon on a BLT sandwich is quite different than having them on top of a greasy cheeseburger.

Having a scoop or two of ice cream alone in a dish is different than having it atop a massive wedge of flourless chocolate cake. In other words, use higher fat foods as garnishes to otherwise lower fat meals rather than doubling up on them in a single sitting.

“Tough” meals refer to the texture of what you’re eating. Think back to the metaphor I used in Chapter 3, which portrayed your stomach as a blender. The stomach blender has to churn a whole lot longer to liquefy coarse-textured foods like salads, celery sticks, popcorn and nuts than it does to liquefy softer-textured alternatives like cooked vegetables, soft corn tortillas and peanut butter. Prolonged churning can increase the likelihood of reflux and the accompanying symptoms of upper abdominal bloating.

If you can’t live without the crunch, and would like to try and keep some tough-textured foods in your diet, here’s how I recommend going about it:

1. Avoid entrée-sized salads or otherwise large portions of raw vegetables; Stick to side salads and appetizer-sized portions.

2. Eat your small appetizer-sized salads at the end of meal--just the French do—rather than at the beginning of the meal when your stomach contents are at their most acidic.

3. Make salads from softer-textured “baby greens” like spinach or butter lettuce rather than tougher-textured leafy greens like kale, cabbage, frisee, romaine hearts and iceberg lettuce.

4. Pay attention to how you tolerate other coarse-textured foods like nuts and popcorn. Large portions are typically a recipe for trouble, though you may tolerate them in small portions, particularly when you’ve been eating in regular three-hour intervals. If even small portions bother you, then seek out the less textured versions of these foods described in Chapter 12.

5. Chew all tough-textured foods exceedingly well. Pretend you’re pre-chewing these foods for a toddler; each mouthful should be smooth and almost ‘pureed’ before swallowing.

If the meal sizing and timing strategies described in this chapter don’t alleviate your sour stomach bloating to a satisfactory degree, then I’d give the GI Gentle diet a try; it’s described in Chapter 12.

Don’t drink alcohol on an empty stomach

Alcohol is a direct stomach irritant and it also relaxes the gatekeeper muscle separating your stomach and esophagus. If you drink on an empty, relatively acidic stomach, that reflux is going to feel mighty bad, and your sour stomach bloating may kick in after just a few sips.

If you choose to drink alcohol, it’s important to eat something small first. Eating decreases the acidity in your stomach and may help coat the mucous lining of your stomach as well. You’ll also want to pace yourself with drinking and avoid drinking to excess. Lastly, if you’re lying down in bed after a big, boozy night out, you’d be wise to leave some TUMS® and an H2 blocker on your bedside table to pop in your mouth before you pass out. You’ll thank me in the morning.

There’s another type belly bloat provoked by eating just like the sour stomach bloating described in this chapter-- but unlike sour stomach bloating, it doesn’t reliably respond to acid suppression. If this sounds familiar, read on to Chapter 5 to see whether functional dyspepsia better describes your personal brand of bloating.

Reprinted with permission. Copyright © 2018 by Tamara Duker Freuman MS, RD, CDN in The Bloated Belly Whisperer and reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Press.