Health experts explain complications of new red meat study

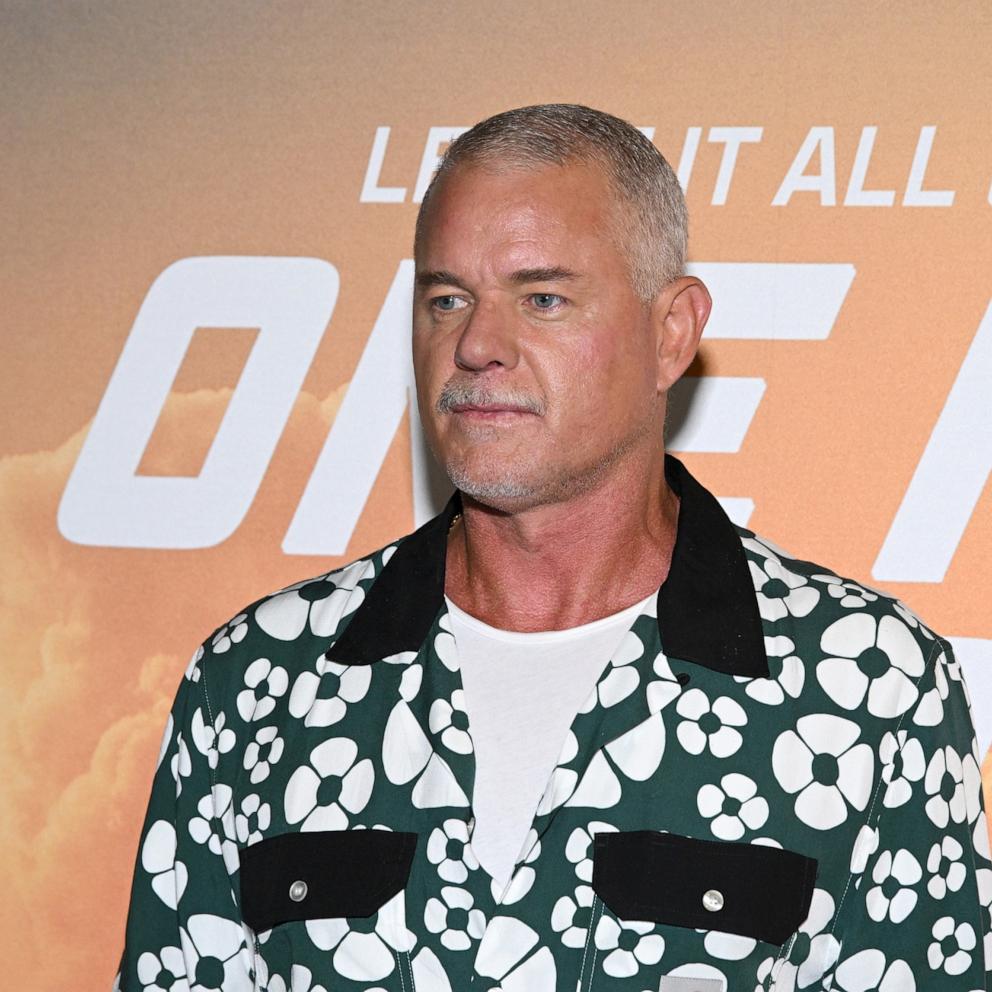

It's not the first time researcher Bradley Johnston has had the nutrition community up in arms over his work.

Johnston, an epidemiologist at Dalhousie University in Canada, is the lead author of a controversial new set of papers challenging the near-universal recommendation to cut back on red meat for health reasons.

The papers, published Monday in the Annals of Internal Medicine, also contained a controversial accompanying recommendation from scientists, suggesting that adults continue eating red and processed meats. The evidence on red and processed meats' link to disease and death is weak and the risk for individuals is small, Johnston and his coauthors concluded.

That recommendation goes against conventional advice from major health organizations like the World Health Organization, as well as the U.S. Dietary Guidelines, which recommends limiting red meat, including processed meat, to one serving a week.

Three years ago, Johnston published a different review on sugar consumption, once again in the Annals of Internal Medicine. The advice was similar: Johnston said there was weak evidence on recommendations to cut dietary sugar.

There was one glaring problem. The review was funded by International Life Sciences, a scientific group backed by companies with a vested interest in the review's results, including Coca-Cola, General Mills, Hershey's, Kellogg's, Kraft Foods and Monsanto.

The outcry against the sugar study was immediate. The point of the study was to show the limitations of research and call for more rigorous inquiry into sugar consumption, Johnston and his coauthors said. Public health and nutrition experts questioned whether that point was made in good faith.

"They're hijacking the scientific process in a disingenuous way to sow doubt and jeopardize public health," Dr. Dean Schillinger, professor of Medicine at the University of California, San Francisco told The New York Times at the time.

The new red meat review has no declared ties to industry funding, but the methodology for the two studies is the same. And once again, experts are asking if Johnston and his coauthors are making a point at the expense of undermining public understanding of nutrition.

Nutrition is notoriously difficult to study. Unlike studies on drugs, people don't want to participate in a decades-long randomized controlled trial, where they eat meat or don't eat meat. Instead, scientists ask people what they are eating and try to make conclusions about the long-term implications of certain foods based on people's health outcomes.

The new red meat research takes a strict approach to nutrition, excluding all research that doesn't fit the highest scientific standards.

It's a tactic often used by the food industry, as well as the drug and chemical industries, to discredit inconvenient research, explained Marion Nestle, professor emeritus of nutrition, food studies and public health at New York University, who has written numerous books on food and nutrition politics.

"Attempts to make dietary guidelines science-based, are doomed to failure because the evidence will never reach high standards of scientific proof," she told ABC News by email.

"I wish it were easier to understand how difficult it is to do nutrition research when you can't lock people up for decades to feed them controlled diets," Nestle said. "We all have to do the best we can to look at the totality of evidence and try to make sense of it."

"The meat studies did not do that," she added

For his part, Johnston thinks if an individual's risk is low, they should be able to make their own decisions on what to eat.

"Some people may think that it is ethical to tell people, from a societal perspective, based on low certainty evidence, to stop or reduce their meat consumption," he told ABC News. "People should look at the very small risk reductions based on low quality evidence and make their own decisions."

But according to health experts ABC contacted, those arguments may do a disservice to the public, which already suffers whiplash when it comes to nutrition advice.

Dr. Frank Hu, professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, called the new research "irresponsible" from both an individual and public health point of view.

Dr. Aaron Carroll, professor of pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine, who penned an editorial about the limits of observational studies that ran alongside the new research, took a more diplomatic view.

Perhaps instead of nutrition guidelines from governmental and research bodies, patients should rely on individualized health and nutrition advice from their physicians, he suggested.

"I try not to ascribe bad motives to other researchers," he said. "I think the public is confused because people [have] legitimate differences in how they view this research."

"Each side would likely say the other is confusing things," he added.

But most people only have so much tolerance for mixed messaging.

"These kinds of wonky methodological discussions confuse the public and lead to what I call nutritional nihilism — the idea that nutrition science is so confusing that we don't have to pay attention to it," Nestle said.