A form of 'ecstasy' could be a new treatment for post-traumatic stress

A form of ecstasy, the illegal club drug known for its a euphoric high, may be able to help people with post-traumatic stress disorder. The pure chemical form of the drug, known as MDMA, is showing potential for therapy.

Approximately seven percent of people in the United States will suffer from PTSD during their lifetimes, according to the National Co-Morbidity Survey published by Harvard Medical School.

Most patients improve with therapy, anti-depressant medications and time -- but some will be unable to shake it, continually having nightmares or flashbacks, persistently reliving a horrible traumatic event. These patients often suffer symptoms so severe, triggering anxiety or depression, interfering with sleep or concentration, that they live with dramatic changes in mood or behavior.

Can MDMA help?

The results of a Phase 2 FDA trial, published Tuesday in The Lancet Psychiatry, looked at patients with chronic post-traumatic stress disorder who were dosed with MDMA for therapy. Phase 2 means it is still in the research phase and more studies will need to be done before it would be available for widespread use. But here is what the researchinger were they’re trying to do.

What is MDMA? How does it work with therapy?

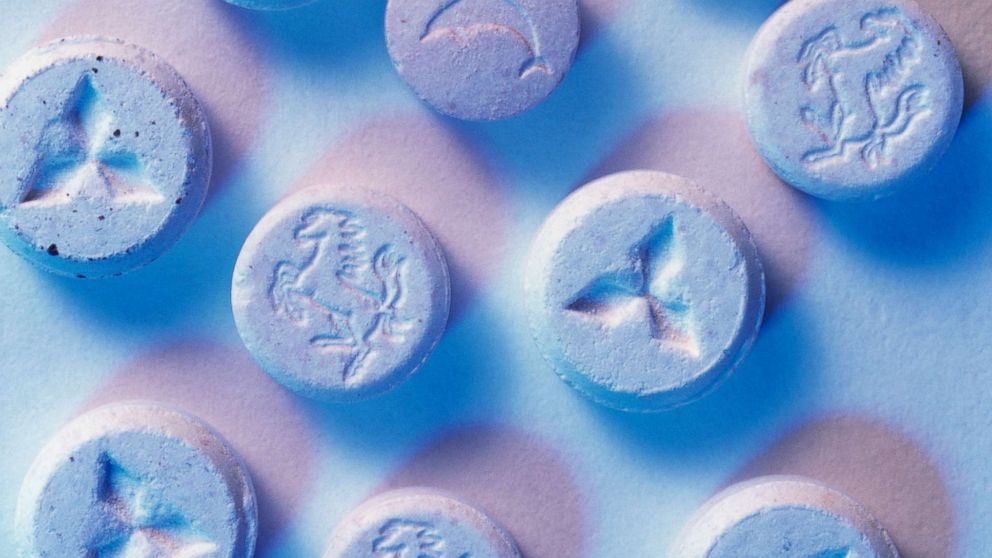

The active ingredient in the recreational drug also known as "ecstasy" or "molly" is MDMA (3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine). Initially described in 1912, it became popular as a recreational drug in the 1970s and 1980s. In 1985, MDMA was labeled "Schedule 1," meaning no accepted medical use and high potential for abuse by the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration.

MDMA alters mood and perception by working on the brain cells that secrete the chemical serotonin, a brain chemical that regulates mood, aggression, sexual activity, sleep and sensitivity to pain. MDMA is chemically similar to both stimulants and hallucinogens and is illegal in most countries.

But mental health researchers wondered if MDMA could help treat a number of mental health conditions; there’s research dating back into the 1970s testing its therapeutic potential.

Dr. Michael Mithoefer, M.D., a psychiatrist in Charleston, South Carolina who researches MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies, or MAPS, describes MDMA as "unique among drugs that decrease anxiety in that it isn’t sedating and doesn’t impair memory."

"People have clear recall of trauma without being overwhelmed by emotions or dissociating and being emotionally numb," he said. "Our model is that MDMA is acting as a catalyst to the psychotherapeutic process, not as a stand-along drug."

MAPS, a private non-profit research group that is helping organize many of the FDA trials, argues MDMA should be considered separately from ecstasy or molly, the often impure street formulations.

What could MDMA treat?

There is certainly interest, but the FDA has approved clinical trials only for limited conditions: Chronic PTSD, severe anxiety related to autism and terminal illness among them. Most of the studies are surrounding PTSD.

MDMA is an optimal choice for use in PTSD treatment, Mithoefer notes, because of “PTSD involves prominent fear responses and the fact that MDMA decreases fear by decreasing activity in the amygdala and increasing activity in prefrontal cortex."

The initial results from Phase 1 and Phase 2 trials are promising –- these are the stages of research which provide the FDA with basic safety data and information about dosing.

In the next stage that begins this summer in 16 sites, Phase 3, researchers can learn more about whether MDMA is effective. European trials are expected in the next year, as well. They expect that positive results in Phase 3 could lead to MDMA being approved for doctors to prescribe.

Researchers warn against self-treatment with street drugs

For most patients, standard treatments for PTSD will work. The patients enrolled in these clinical trials are the most severe cases, often having failed standard therapy or anti-depressant medications. Also, these researchers are studying MDMA-assisted psychotherapy, not MDMA alone.

The therapy couples the medicine with close supervision by medical providers. Mithoefer, who has conducted many studies on MDMA-assisted therapy, notes patients “should know that like any other drug, MDMA has risks as well as benefits, and our participants were carefully screened for medical problems and had considerable psychological support, including preparation and follow-up.”

The DEA still considers MDMA a Schedule I drug, meaning it is against the law to possess or distribute it.

MDMA has stimulant properties and has prominent side effects: sweating, muscle cramping, tremors, increased muscle tension, hyperthermia, an increase in heart rate, and increase in blood pressure. It may result in severe dehydration resulting in damage to the kidneys.

The National Institute of Drug Abuse warns that street formulations confiscated by police initially reported as “pure” MDMA have been mixed with other agents such as cocaine, methamphetamine or bath salts, which can have extremely dangerous side effects and symptoms.

What about Ketamine treating PTSD or depression?

Ketamine and MDMA are different drugs. Both agents have been used as recreational agents, though Ketamine is a “Schedule III” agent, according to the DEA, meaning it is a drug with a moderate to low potential for physical and psychological dependence.

Separate research efforts are exploring ketamine for several mental health disorders, including depression and PTSD. While some providers have adopted ketamine in treating mental health disorders, it is an “off-label” use, as the FDA has only approved Ketamine for anesthesia purposes.

David J. Kim, MD is a final year Emergency Medicine resident at the University of California, Los Angeles, working with the ABC News Medical Unit in New York.