Flint, Michigan Issues State of Emergency After Threat of Lead Poisoning in Children

— -- A change in the water source has exposed children in Flint, Michigan, to potentially dangerous levels of lead, prompting the city to issue a state of emergency for what is being described as a "man-made disaster."

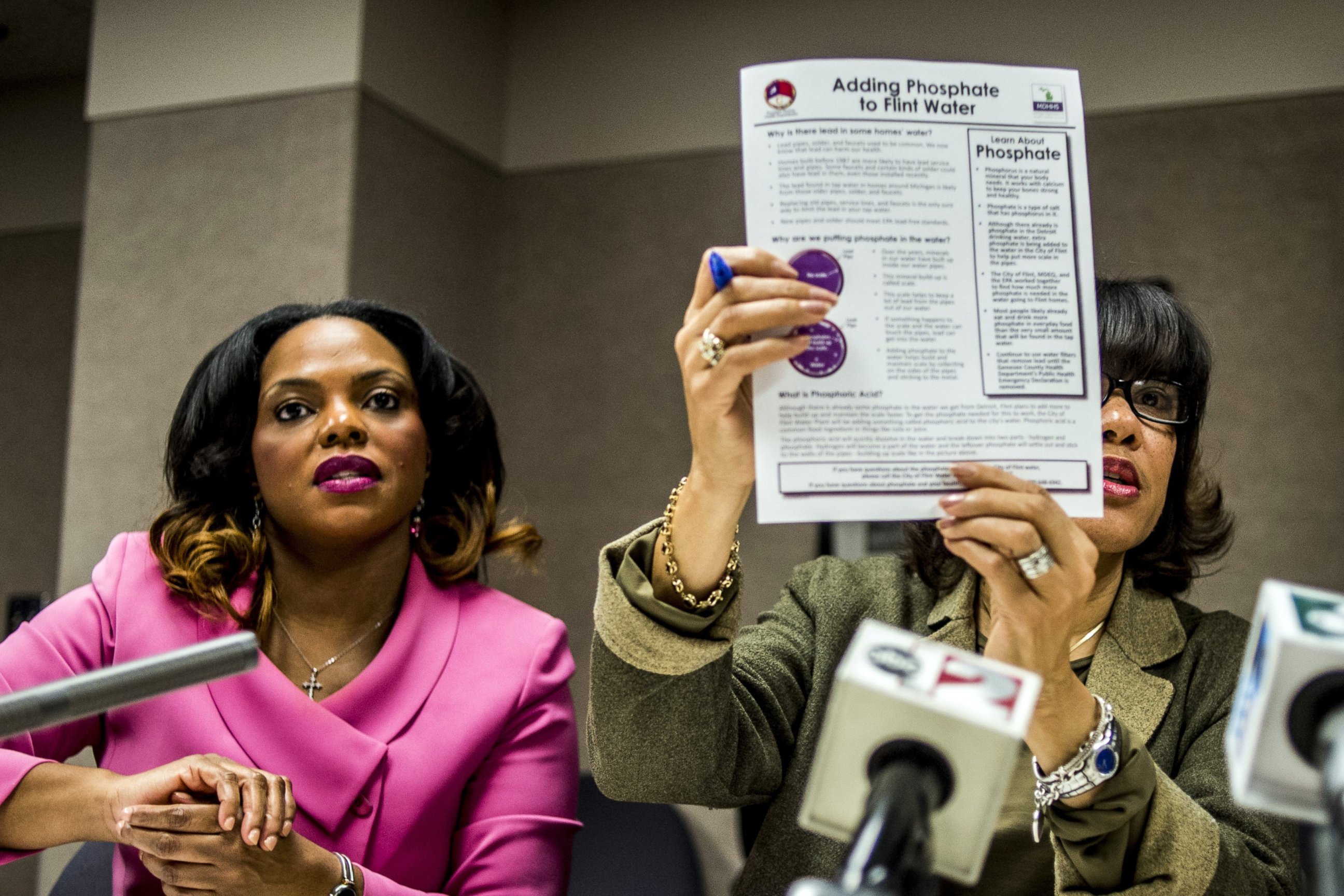

Flint Mayor Karen Weaver declared the state of emergency Monday in response to what she called the "man-made disaster caused by the city switching to the Flint River as a water source.”

The city had disconnected from Detroit’s water supply in April 2014 and began drawing its water from the Flint River.

"This switch has resulted in elevated lead levels in drinking water, which prompted both the city and the County Health department to issue a health advisory earlier this year," the mayor's office said.

The city subsequently switched its source of water back to the Detroit Water and Sewerage Department Oct. 16, but lead levels still "remain well above the federal action level of 15 parts per billion in many homes," the mayor's office said.

The office urges residents to continue using water filters.

The city, which has not responded to ABC News' request for comment, realized savings of about $4 million annually by using the Flint River, according to The Associated Press.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services said the switch to the Flint River was intended as a stop-gap measure until the completion of a pipeline to Port Huron Lake as the source for Flint’s water. The problem is that the river water wasn’t treated properly, a state spokeswoman said, so it drew lead from the pipes into the water supply.

The new water from Detroit does include the anticorrosive chemicals needed to the keep the lead from leaching but it takes time for them to work, which is why there’s still lead in the water.

The pipeline for the water from Port Huron Lake should be completed sometime in the next year, the spokeswoman said.

Meanwhile, she added, declaring a state of emergency may help get federal funds and assistance for future programs and therapies aimed at helping children exposed to the lead.

Exposure to lead can be especially dangerous for young children. Doctors at the Hurley Medical Center in Flint, Michigan, released their own report in September after seeing children with increasing levels of lead exposure.

Doctors at the center looked at blood from children younger than 5 in a report released this fall and found that 4 percent of the 840 children in Flint tested after the water system was changed to the Flint River had elevated levels of lead in their blood, or over 5 micrograms of lead per deciliter. This is the amount cited by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as the cut off for “blood lead levels that are much higher than most children’s levels.”

Of the 727 children in the county, but outside of Flint, who were tested by the hospital, just 1 percent were found to have elevated lead levels.

Experts, including those at the CDC, say there is “no safe blood lead level” for children and that lead in water accounts for 50 percent of lead ingested by children. While lead poisoning can affect anyone, children are particularly vulnerable because of their underdeveloped neurological system.

Dr. Donna Seger, professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine at Vanderbilt University in Tennessee, said the lead will stay in the body until it is excreted or removed with medication. The lead can also “hide” in tissues or bone during a long exposure so that it can remain in the body even after treatment is given.

“The more vulnerable the nervous system, the greater potential lead has to cause problems,” Seger said, explaining that the metal can act as a neurotoxin in children. “The main concern is the cognitive issue that it causes.”

Symptoms of long-term lead exposure can include anemia, brain swelling or behavioral issues like anxiety or ADHD. Cognitive impairment has been known to occur in children with more than 10 micrograms of lead per deciliter.