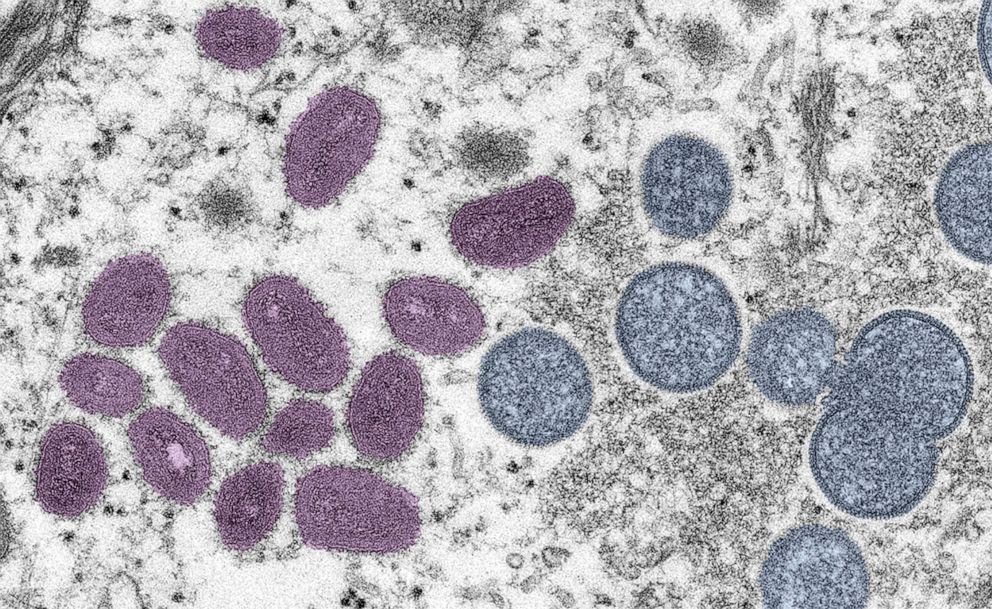

FDA's move to stretch monkeypox vaccine supplies could pay off, experts say

The Food and Drug Administration announced an emergency use authorization to move forward with their plan to stretch out the current monkeypox vaccine supply with a new injection method that will try to stretch one dose into five. Vaccine experts say that the scientific rationale behind this decision is sound, but technical challenges with the rollout technique may still be ahead.

"In recent weeks, the monkeypox virus has continued to spread at a rate that has made it clear our current vaccine supply will not meet the current demand," FDA Commissioner Bob Califf said Tuesday during a press briefing.

But this swift decision has some asking if this way of giving a vaccine that is still experimental.

Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, deputy coordinator for the White House Monkeypox Response, sought to reassure gay, bisexual and men who have sex with men -- the group most affected by the outbreak right now -- that the new strategy is evidence-based.

"I think that the due diligence done by the FDA, looking into the data, should assure them that the vaccine is immunologically equivalent and safe," Daskalakis, a leading expert on LGBTQ health, said during a Tuesday briefing.

Experts say the scientific rationale is sound, but the data isn't robust

The data Daskalakis is referring to comes from a 2015 study that evaluated both ways of administering the vaccine, that found "a similar immune response," according to the FDA. Other data comes from smallpox and influenza vaccines.

"We look at the totality of the available scientific evidence and we bring that together to try to do the best by public health," Dr. Peter Marks, FDA's vaccine chief, said on Tuesday.

Vaccine scientists interviewed by ABC News agreed that the scientific rationale supporting the new injection technique is strong, but note prior studies have been small.

"The data supports this based on the original clinical trial data and their approval from FDA," Dr. Richard Kuhn, Krenicki Family Director of Inflammation, Immunology, and Infectious Disease at Purdue University, told ABC News.

Dr. Dan Barouch, Director, Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center says it's crucial to continue collecting data to better understand if the new injection technique will be equally effective in this outbreak.

"There is some data, but it's a small amount of data — and it needs to be studied in larger numbers with more sophisticated assays that we have today with the actual vaccine that's being used right now," Barouch told ABC News.

The National Coalition of STD Directors, a nonprofit representing sexual health clinics that have been on the frontlines of the current outbreak - questioned the decision. Without clear data on efficacy, giving smaller, shallower injections could give people a false sense of security, they argued on Twitter.

Trickier injection method can be taught

Healthcare providers will need to be trained in how to give shots between layers of the skin, instead of the more typical deeper injections below the skin. The technique is not overly complex and has been done in the past with other vaccines. But because it is slightly more difficult, the shallower injection into the skin is not commonly used.

"There is a lot of history of getting vaccines by the intradermal route, but not recently," Barouch said. "Most people are not trained or experienced in administering vaccines by the intradermal route."

Despite challenges, vaccine scientists say dose sparing technique could still pay off

"Currently we have a larger demand for monkeypox vaccine than we have doses of the vaccine. I am confident this is why a dose sparing strategy was authorized," Dr. Robert Frenck, director of the Vaccine Research Center at Cincinnati Children's Hospital Medical Center, told ABC News.

Kuhn also agrees with FDA's decision to allow shallower injections to stretch limited vaccine supply.

"The guidance on the intradermal is supported by earlier trials and is meant to increase availability of the current vaccine stocks," Kuhn said, but warned that we need to be thinking about opening vaccine eligibility.

"I would prefer that we move now with this attenuated non-replicating vaccine," he continued. "This is not a gay disease, and my concern is that we should be open to larger segments of the population, independent of sexual orientation, for the application of diagnostics and therapeutics."

"Now is the time to try to get in front of this outbreak since we have a reasonable history of smallpox vaccination and some data on monkeypox," he added.

But no one can perfectly predict the future of this outbreak.

"Only time will tell if this was the right decision or not," Barouch said.

Dr. Jade A Cobern, board-eligible in pediatrics, is a member of the ABC News Medical Unit and a general preventive medicine resident at Johns Hopkins.

ABC News' Cheyenne Haslett and Sony Salzman contributed to this report.