Father aims to improve CDC reporting of illnesses with 'polio-like' symptoms among children as AFM cases grow

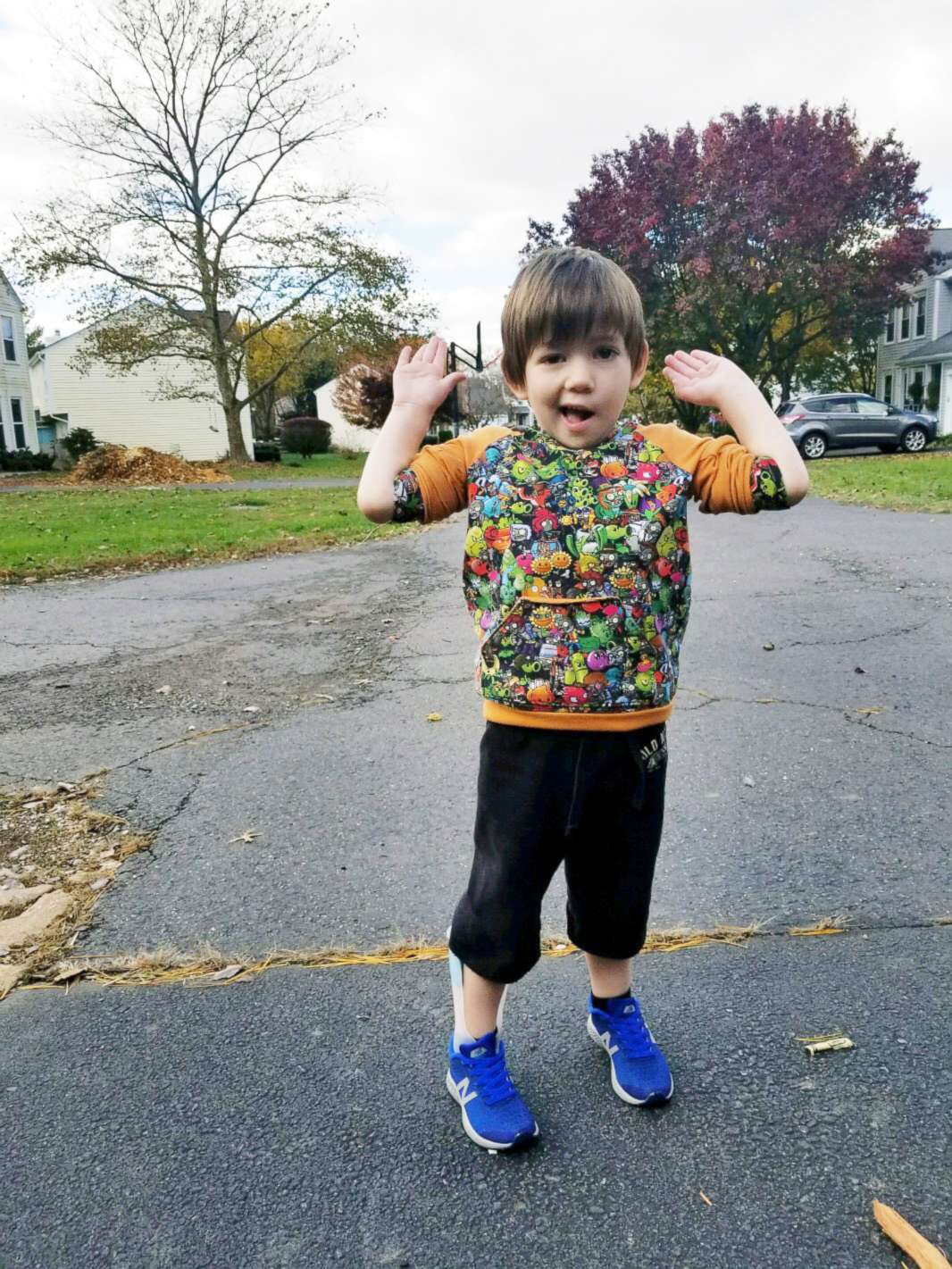

For the last two months, Jeremy Wilcox has been fighting for a diagnosis of acute flaccid myelitis, or AFM, for his son.

"I've seen the good and bad of the health care system," the Herndon, Virginia, father told ABC News.

During the second week of September, Joey Wilcox, 4, came down with a common cold. He was running a fever and had upper respiratory problems.

On Sept. 25, he woke up with paralysis on the left side of his face. The next day, as Joey's fever continued, his parents rushed him to the hospital. Joey was unable to walk so Wilcox’s wife carried him into the emergency room. After examining Joey, Wilcox said, doctors told the couple that their son could have a virus and then discharged him.

Less than 48 hours later, Wilcox told ABC News, his son had paralysis from his neck down. They took him to Fairfax Inova Children's Hospital in Virginia. After doctors ordered a CT scan and spinal tap, they uncovered swelling in Joey's spinal cord from the brain stem down.

Joey, who'd lost all bodily control, was in the hospital for 36 days. Doctors continued to aggressively test for viruses but the results came back negative.

In October, doctors diagnosed Joey with multifocal encephalomyelitis because of the damage in the gray matter of his spinal cord. Upon transfer to Kennedy Krieger Institute in Baltimore, however, he was sent for treatment of AFM at the request of a neurologist.

Despite his symptoms mirroring those of the mysterious symptoms, Joey has yet to be officially diagnosed with AFM, his father said.

Over the years, ABC News has reported on hundreds of children left paralyzed by AFM, a disease that appears to spike every two years in the U.S.

AFM is a condition that has polio-like symptoms such as partial paralysis. The virus mostly affects children and young adults. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said it does not know why the condition is affecting these individuals, but many believe it is caused by viruses.

As of Monday, according to the CDC, there were 106 confirmed cases of AFM this year, and 167 more under investigation in 29 states. The organization is still trying to find a definitive cause.

Dr. Nancy Messonnier, the director of the CDC's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told reporters during a telebriefing on Nov. 13 that there had been "no deaths among AFM patients reported to CDC in 2018.”

That statement, however, drew harsh criticism from Wilcox and other parents of children with AFM who feel as though the CDC isn’t doing enough to properly report cases and deaths from whatever is causing these polio-like symptoms.

Wilcox said he'd reached out to Dr. Anne Schuchat, the CDC's deputy director, who then arranged a meeting between herself, officials from the National Institutes of Health and parents to take place in Washington, D.C. He said 18 parents attended the meeting, including parents who said their two children had died of AFM this year.

Wilcox said he and other parents had come to the meeting to ask that the deputy director make AFM a nationally notifiable disease and reporting of all cases of AFM mandatory.

Currently each state's health department has its own list of patients reported with AFM but many medical professionals are not immediately reporting suspected cases, Wilcox said.

Parents also called for increased transparency, better communication, effective protocols and an update on the potential causes of AFM. They pointed to a most recent CDC report that still uses 2014/2016 data.

“The challenge facing the CDC and the issue of misdiagnosing children is the complexities of symptoms,” Wilcox said.

Many of the parents who met with Schuchat and the NIH are continuing their work in Washington D.C., meeting with other health officials, as well as speaking with their prospective lawmakers.

“We have become parent advocates for AFM and we want to make it easier for others. Parents really want to know, why our children are susceptible to this,” Wilcox said.

On Monday, the CDC announced that it had established an AFM Task Force to aid in the ongoing investigation to define the cause of the illness and improve treatment. Schuchat also informed parents that the task force would develop a comprehensive research agenda and bring on additional neurologists to look at MRIs.

“I appreciated the opportunity to listen to the families and share information about CDC efforts in responding to AFM,” Schuchat told ABC News after the meeting with parents.

Wilcox called the task force "a positive development."

"I am encouraged to hear additional resources are being assigned at the CDC and experts will be collaborating with the CDC to discuss better ways to diagnose and treat patients,” Wilcox told ABC News on Tuesday.

Currently, the CDC states there is no effective treatment for children with AFM but Wilcox said that his son is making tremendous progress with intravenous immunoglobulin therapy (IVIG), a therapy that can help people with weakened immune systems.

Along with a regimen of steroids and constant therapy, Joey has a long journey ahead until he can potentially reach full mobility.

"I’ve learned that you have to be your child’s advocate," said Wilcox, who now plans to work with other parents to set up a nonprofit to further advocate for families.