Family speaks out after man receives pig heart in 1st of kind transplant

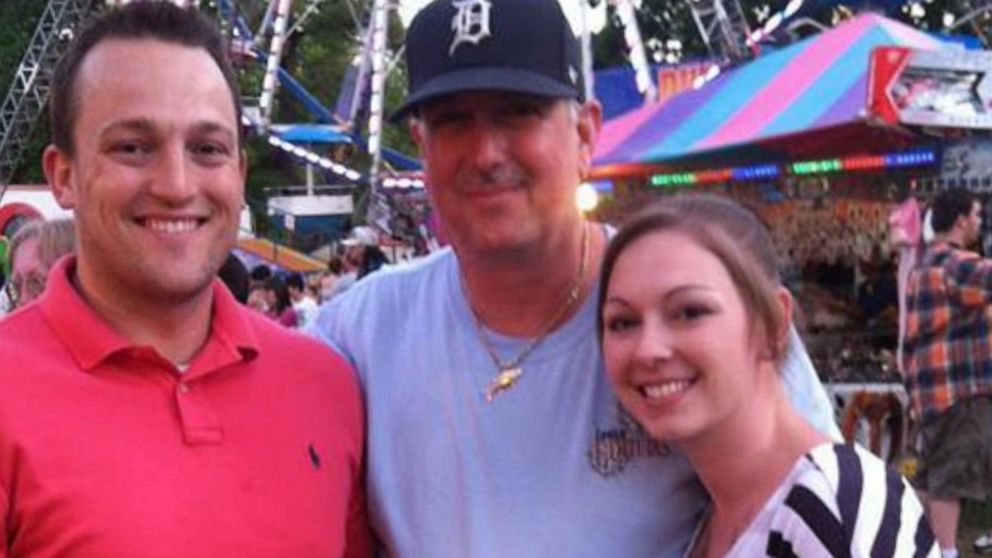

A 57-year-old man who underwent a first-of-its-kind heart transplant involving a genetically-modified pig heart is in a "much happier place" after the transplant, according to his son.

David Bennett Sr., of Maryland, suffered from terminal heart disease and was deemed ineligible for a conventional heart transplant because of his severe condition, according to University of Maryland Medicine, where Bennett underwent the transplant.

On New Year's Eve, University of Maryland Medicine doctors were granted emergency authorization by the Food and Drug Administration to try the pig heart transplantation with Bennett, who had been hospitalized and bedridden for several months.

Bennett said he saw the risky surgery as his last option.

"It was either die or do this transplant. I want to live. I know it's a shot in the dark, but it's my last choice," he said the day before the surgery, according to University of Maryland Medicine. "I look forward to getting out of bed after I recover."

Bennett was so sick before the transplant that he was on an extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) machine -- which pumps and oxygenates a patient's blood outside the body -- and had also been deemed ineligible for an artificial heart pump, according to University of Maryland Medicine.

"His level of illness probably exceeded our standards for what would be safe for human heart transplantation," said Dr. Bartley P. Griffith, a professor in transplant surgery at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

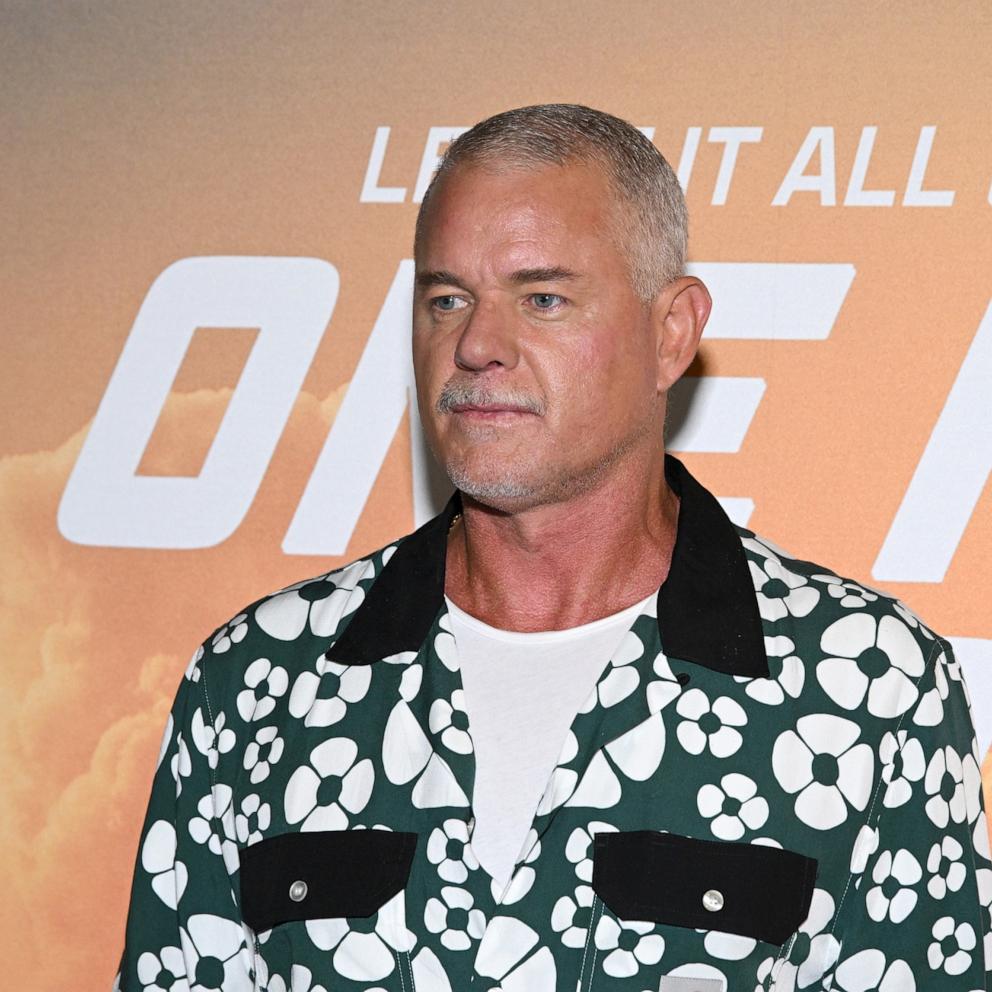

It was Griffith who surgically transplanted the pig heart into Bennett. He and a team of researchers have spent the past five years studying and perfecting the transplantation of pig hearts, according to University of Maryland Medicine.

Pig hearts are similar in size to human hearts and have an anatomy that is similar, but not identical.

So far, Bennett's body has not rejected the pig heart, which experts said is the biggest concern after a transplant.

Xenotransplantation, transplanting animal cells, tissues or organs into a human, carries the risk of triggering a dangerous immune response, which can cause a "potentially deadly outcome to the patient," according to University of Maryland Medicine.

"It is a game-changer," Dr. Muhammad Mohiuddin, professor of surgery at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, who oversaw the transplant procedure with Griffith, said. "We have modified 10 genes in this in this pig heart. Four genes were knocked out, three of them responsible for producing antibodies that causes rejection."

Mohiuddin and Griffith said they are now closely monitoring Bennett to make sure his body continues to accept the new heart.

"He's awake. He is recovering and speaking to his caregivers," said Griffith. "And we hope that the recovery that he is having now will continue."

Speaking of the possibility of rejection, Griffith added, "The pig heart will be attacked by different soldiers in our body, different immune players can take it out and we have designed a treatment plan, in addition to the humanized, genetically-edited heart, to try to account for that."

Bennett's son, David Bennett, Jr., told "Good Morning America" the transplant provided his father a "level of hope."

"Hope that he could go home and hope that he could have the quality of life that he's so much desired," Bennett, Jr said. "He's in a much better place and a much happier place right now following this transplant procedure. He is happy with where he is at. Happy with the potential to get out of the hospital."

While the type of transplant Bennett received is groundbreaking, experts said it does not minimize the ongoing need for human organ donations.

Around 110,000 people in the United States are on the organ transplant waiting list, and more than 6,000 patients die each year before getting a transplant, according to the Department of Health and Human Services.

"Whether it's 3-D printing or growing organs in a lab setting or donations, we desperately need more organs," said ABC News chief medical correspondent Dr. Jennifer Ashton, a board-certified OBGYN.