Here's what to know about fall COVID boosters

This is a MedPage Today story.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) will weigh in on newly authorized fall COVID boosters this week, in a manner unprecedented during the pandemic -- without data from human clinical trials.

While most experts agree that there are no safety concerns, and many support the FDA's attempt to keep up with viral variants, others have pointed out gray areas and open questions when it comes to omicron-targeting bivalent vaccines.

That includes whether boosters with components targeting omicron would offer a significant advantage in terms of efficacy -- particularly, protection against infection -- over boosting against the ancestral strain of the virus alone.

Regulatory recap

To recap, the regulatory process for fall boosters started earlier this summer.

On June 28, the Food and Drug Administration's Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) voted 19-2 to recommend the use of an omicron-specific component in future boosters. Their review was based on human clinical trial data from a bivalent booster containing the ancestral strain and the BA.1 variant, showing sufficient levels of neutralizing antibodies after the fourth dose.

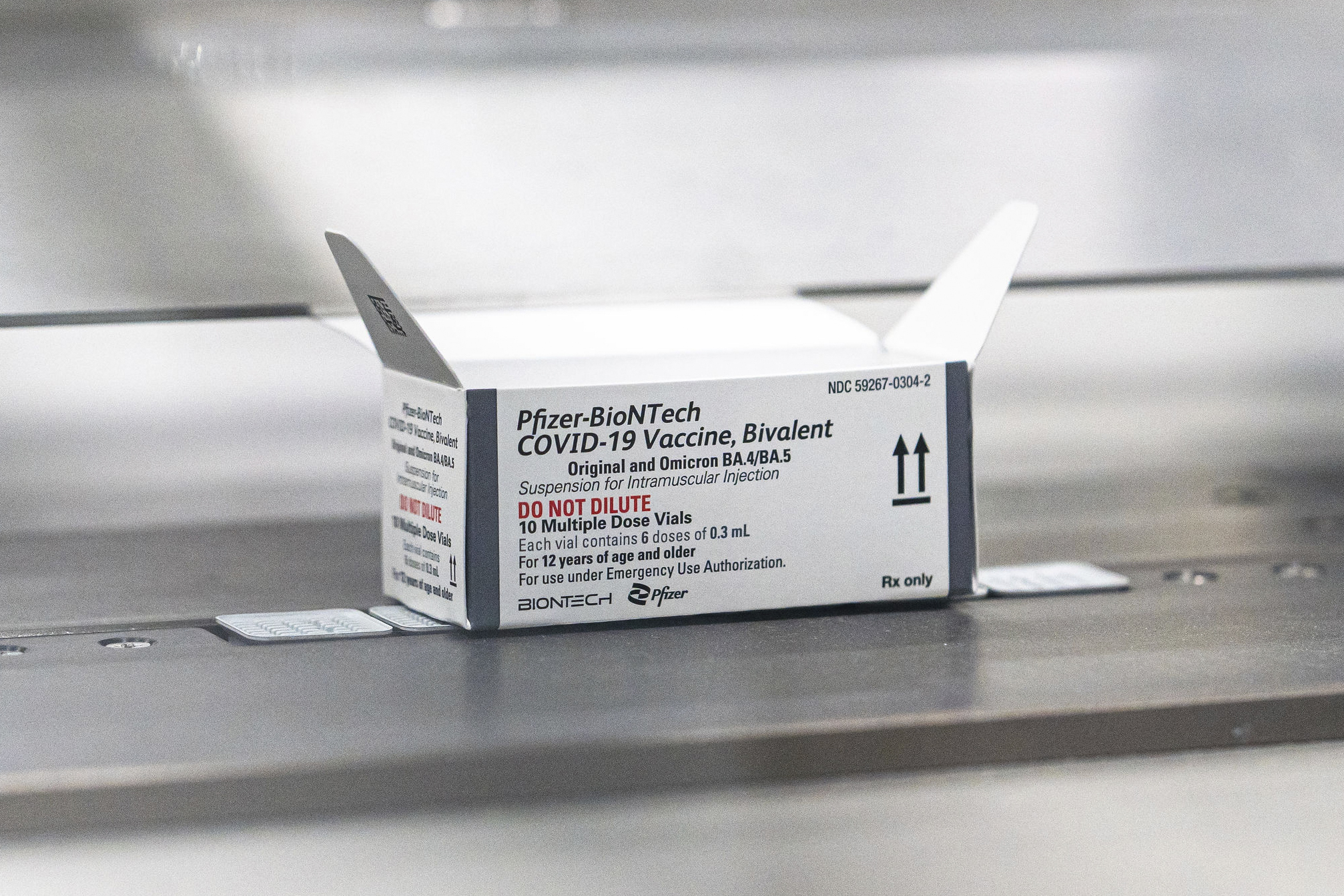

But most committee members voiced support for a bivalent vaccine that included the ancestral strain plus the BA.4/5 variants, even though data from a human clinical trial wouldn't be available before fall.

That would make the authorization process for this and possibly future COVID boosters similar to that for annual influenza vaccines, which relies on immunogenicity data from mouse studies.

Indeed, Pfizer has presented data from a mouse study, showing that BA.4/5 monovalent and bivalent boosters sufficiently raised neutralizing antibody levels against all omicron variants.

Pfizer and Moderna are both starting human clinical trials of BA.4/5 boosters this month -- a 30-mcg dose for Pfizer and a 50-mcg dose for Moderna -- but those won't be concluded before shots likely start going into arms in the coming weeks.

The unknowns

While proponents tout the positives of moving quickly, others have raised several concerns, including not knowing whether a BA.4/5 boost will offer better protection against infection than another boost with the ancestral strain alone.

Dr. Paul Offit of Children's Hospital Philadelphia, who participated in the June 28 VRBPAC meeting, told MedPage Today that the human data on BA.1 boosters were "underwhelming."

Depending on the company, he said, there was a 1.5-fold to 1.75-fold increase in neutralizing antibody titers in the group that got the bivalent vaccines, and that's "not likely to be a clinically significant difference."

That could be related to "imprinting," Offit said, which is also referred to as "original antigenic sin." The concept is that the immune system response is bolstered against the strain that a person was initially exposed to.

"You largely are hooked into that ancestral strain, so it's hard to boost in a big way with BA.4/5 vaccines," Offit said. "If I gave a monovalent BA.4/5 vaccine to a 10-year-old with no previous vaccination or natural infection, you'd see a dramatic increase in neutralizing antibodies."

Dr. John Moore, professor of microbiology and immunology at Columbia University in New York City, noted that the Pfizer mouse study data actually suggested better results with a monovalent BA.4/5 booster. Thus, it's not clear why a monovalent booster isn't moving forward at this time, he said.

Moore added that recent modeling data -- albeit, a preprint, and not clinical data -- suggest there wouldn't be much of a difference in outcomes if people received a booster of the ancestral strain alone versus the Omicron-targeted booster.

"A great deal of time, effort, and money have now gone into making new boosters that will be little better than what we already had available in large quantities," Moore told MedPage Today in an email.

He added it would be a "mistake if the public was persuaded that the new boosters are a super strong shield against infection, and hence increased their risk and exposed themselves to more virus."

Several experts also expressed concerns that if the public perceived that the bivalent boosters were problematic because they only have animal data behind them, hesitancy could increase. That's troubling given that only about 30% of the U.S. population has taken a booster dose, they said.

Still others think FDA is on the right track. Dr. Robert "Chip" Schooley, an infectious diseases expert at the University of California San Diego, told MedPage Today in an email, "I think the call was the right one."

"Coronavirus-induced immunity (whether vaccine- or infection-driven) wanes quickly and we have a large number of unboosted and under-boosted people in the population and are poised for a recrudescence of infection as people go indoors for the winter," Schooley said. "Thus, there is not time for a comparative trial with clinical efficacy endpoints before the need to roll vaccination out in anticipation of the winter surge."

He said he would have liked to see a clinical trial "embedded in the fall rollout in which people were randomized to a 'legacy' vaccine or a new one with a subset of patients being studied for immunogenicity versus a range of variants and clinical outcomes in the full cohort" -- but that he wouldn't advocate "continuing with the legacy vaccine for the next six months, which is what would be required to do a properly controlled clinical trial."

He concluded that COVID vaccines are "likely headed toward where flu vaccines have gone."

That certainly seems to be a foregone conclusion, as Biden administration officials have already touted the value of omicron-targeted bivalent boosters. White House COVID-19 Response Coordinator Dr. Ashish Jha called it the "first major upgrade of the vaccines...in the last two and a half years."

CDC Director Dr. Rochelle Walensky told the podcast "Conversations on Health Care" that bivalent boosters "shouldn't impact safety at all."

If the country waits for human data, she said, "we would be using what I would consider to be a potentially outdated vaccine...It's best to use a vaccine that's tailored to the variant we have right now."