With all eyes on coronavirus testing, some researchers say 'group testing' could make up the shortage

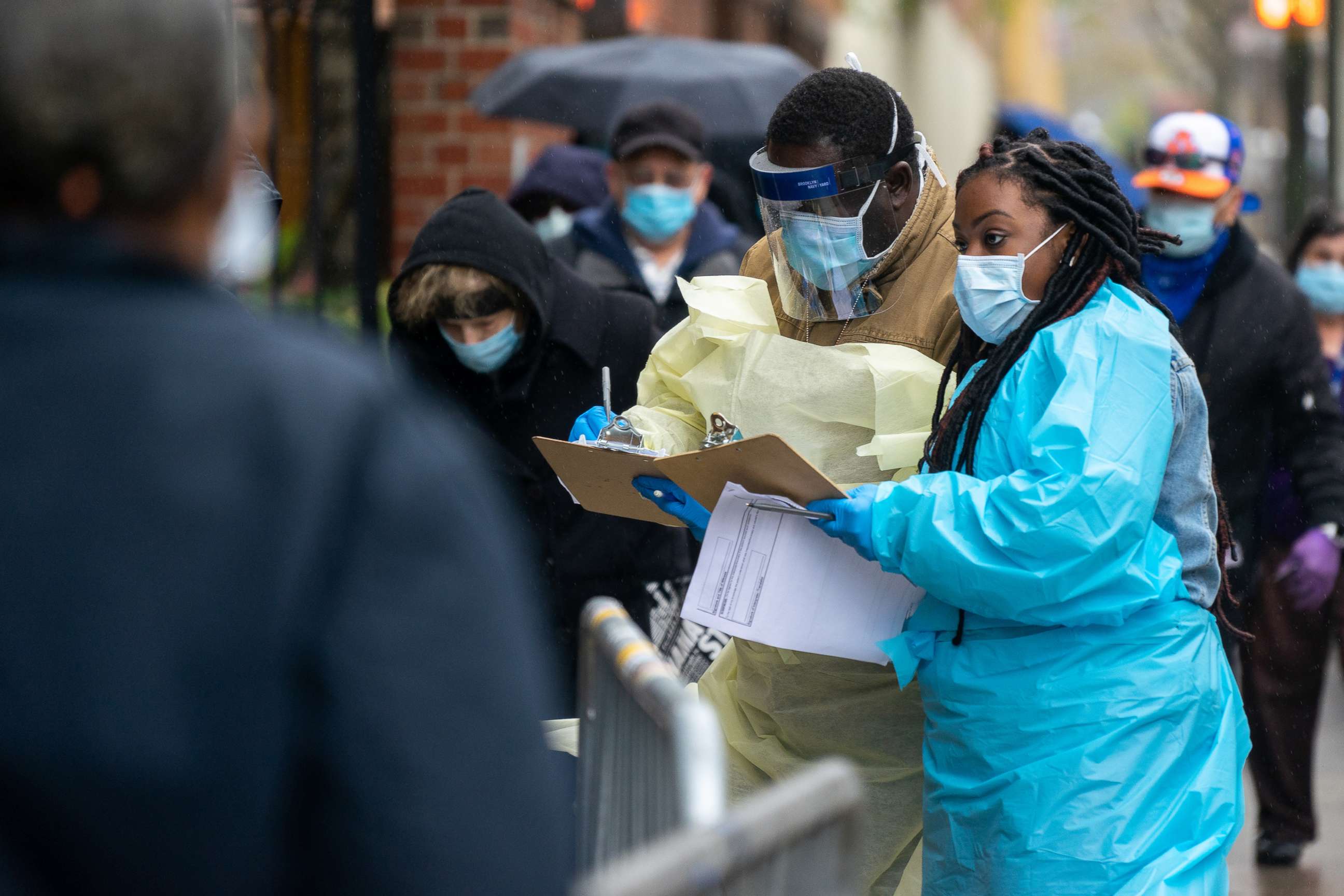

When the nation's top health officials testified virtually before lawmakers Tuesday, a major focus on getting a handle on the coronavirus was the ability to test more Americans, long seen as one of the keys to safely re-opening the country.

Though Health and Human Services Secretary Adm. Brett Giroir lauded a testing effort that was expanding weekly, Republican Sen. Mitt Romney, R-Utah, said he found America's "testing record nothing to celebrate whatsoever" and described a nation that was racing to catch up.

In recent weeks the U.S. has ramped up testing significantly to the point where officials said more than 9 million coronavirus tests have been conducted nationwide.

Experts have said the U.S. capacity has to be far greater to fully re-open the country -- though the total number of tests needed and the amount of re-testing necessary is a matter of debate.

But some researchers say there could be a way to help solve the testing riddle, not strictly by producing more tests, but by getting much more out of each individual test through a method known as "group testing."

Put simply, the method involves the mixing of several samples for a single test, which could theoretically reveal if the group as a whole is coronavirus positive or negative. There are some significant drawbacks and open questions about the method, but its proponents say that if it works, it would stretch the current one-to-one test-to-individual ratio to reach many more Americans.

And some academics, led by an economist and a data scientist at two U.S. universities, want to take the idea even farther by turning each household into a single group and adding some statistical algorithms to the equation to spread the tests thin enough to cover the entire nation, household by household.

"If you could test everybody, you can capture and kill the virus," said Laurence Kotlikoff, professor of economics at Boston University, who proposed the mass group testing strategy in Forbes late last month. "We need to go on the offensive. We are playing defense."

While there are many unknowns, including basic concerns about whether group testing would be accurate enough and the acknowledgement that an effort has never been attempted on a large scale, Dr. John Brownstein, an epidemiologist at Boston's Children's Hospital, said the concept is worth exploring.

"This creates efficiency and enables scale of testing which is what we desperately need right now," said Brownstein, an ABC News contributor.

He said that mid-pandemic is never the best time to attempt new scientific methods, but said "as long as we can work out the metrics of false positives and false negatives, this makes sense."

Dr. Ashish Jha, Director of the Harvard Global Health Institute, is unaffiliated with the research group behind the nationwide proposal, but he said in general on a smaller scale he's been "pushing a lot of states and talking to the White House about pooling because pooling really works as a screener."

Even if nationwide group testing isn't the solution to America's testing problem, Jha suggested pooling could be used as an early warning system for high-risk areas of infection, by testing groups of people in places like nursing homes, food processing plants and jails, all of which have shown to be transit hubs for the virus, as ABC News recently reported.

Kotlikoff, a former 2016 write-in presidential candidate, said he has conveyed the national group testing plan to some members of the White House coronavirus task force, but so far he has not received any word back from the administration.

The Food and Drug Administration, which regulates testing equipment and procedures, said it was aware of the strategy, but was non-committal in response to questions about how seriously the option is being considered by the federal government.

"FDA is open to a variety of novel testing ideas, such as specimen pooling, and encourages all test developers to reach out to us to discuss possible validation approaches," a spokesperson for the agency told ABC News Tuesday.

For questions about any potential nationwide effort, the FDA referred ABC News to Health and Human Services. There, a spokesperson told ABC News Wednesday the department is "working with innovators and companies to establish the evidence for pooled testing."

"This technique could be helpful in areas of low infection prevalence and needs to be validated," the spokesperson said. "The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) has taken a multifaceted approach on COVID-19 testing to control and ultimately end this outbreak."

How 'group testing' would work

On a much smaller scale, a version of group testing for coronavirus has already been attempted in the U.S., for a study in Nebraska that was published in the American Journal of Clinical Pathology last month.

The study used a few dozen specimens in total and mixed several samples together in groups. It then used a single test to see if any group as a whole was positive. If it was, then additional testing was done to individual samples to try and identify the singular offending sample.

But if the result was negative, it would indicate that every sample in the bunch is virus-free -- after just one test.

In the Nebraska study, researchers determined that the five samples mixed together was the right number, and said that using such a method would result in using 57% fewer tests on average to reach the same number of individuals.

“Group testing will reduce the number of tests needed to determine who is positive or negative. It increases the overall testing capacity because with a fixed number of resources it will allow you to use those resources to test more people,” Chris Bilder, professor in the department of statistics at University of Nebraska-Lincoln and an author of the Nebraska study, said in an interview with ABC News.

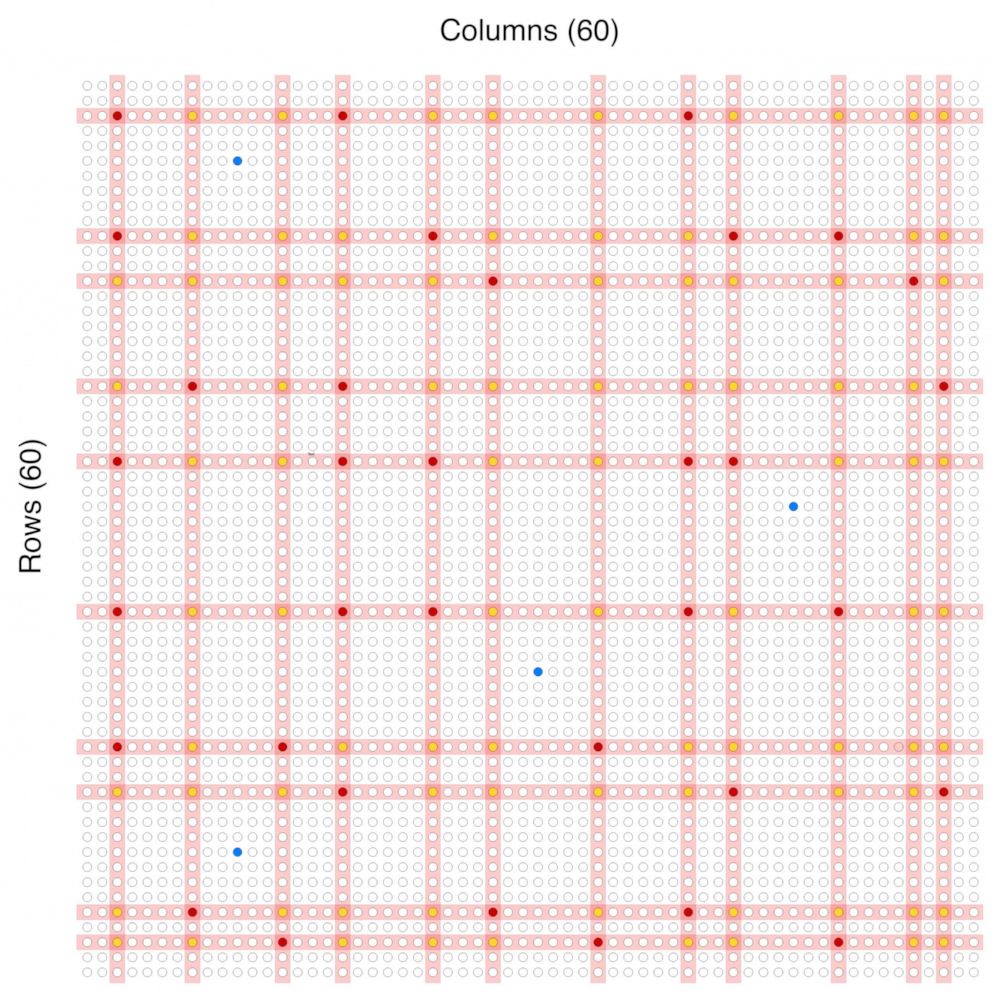

For the much larger, nationwide scale proposed by Kotlikoff, and described in more detail in an as-yet unpublished white paper from Cornell data scientist Peter Frazier, whole households would mail-in their own mixed sample to a lab.

The sample would then be mixed in with about 60 other households to form a larger group. A total of about 4000 households, in groups of 60, would be tested all at once using about 120 test kits.

If a group comes back negative, all 60 households in that group could be cleared.

By using some mathematical probability calculations and comparing which households were in groups that tested positive more than once, it should be possible to identify which particular household is most likely to be positive. Those households would then be encouraged to stay home in isolation for at least two weeks.

Using the system, the researchers claim that around 10,000 people could be tested at a time using around 120 tests, a small fraction of the number of test kits that would have been required if every person was tested individually.

To implement the idea nationwide, the researchers estimate the U.S. would need to conduct around 6 million tests per week for at least a month. It's a large number, but the U.S. conducted some 2 million tests in a week earlier this month, according to the COVID Tracking Project, so the researchers say it's an obstacle that can be overcome. After that initial span of mass testing, additional testing of trouble spots could take place on a smaller scale.

Frazier, an associate professor in the School of Operations Research and Information Engineering at Cornell who was the lead author of the white paper, said the method, along with effective contact tracing, could provide the "ability to send everybody back to work and return the economy more or less to normal with the testing capacity that we have instead of the testing capacity we wish we had."

Frazier said some of his Cornell colleagues whose academic focuses include population medicine, molecular biology as well as animal medicine were looking into how group testing could be used for universities as well.

While the idea of grouping samples may raise eyebrows, a version of pooled blood testing is being used today. The American Red Cross tests blood donations for hepatitis B “in mini-pools of 16 individual donation samples,” according to the American Red Cross website.

The very real drawbacks and open questions

The most immediate problem when it comes to group testing, researchers said, is the "dilution effect."

Mixing a bunch of samples together raises the possibility that each individual sample is diluted so much that virus levels are too low to be detected at all -- meaning the tests could result in false negatives, and give people a false sense of security that they are virus free.

Using group sizes of 60 households per group, researchers estimate they could see a 10% false negative rate and a false positive rate as high as 30%. Meaning if the method were to be implemented, there would be a significant percentage of households who would think they're in the clear, when they're not, and others who would be told to isolate, when it's unnecessary.

Bilder said that the nationwide proposal included some "good ideas" and the grouping of household members "seem[ed] like a reasonable approach" since it was likely that if one person in the home was positive, others could be as well.

But he said that it remains to be seen how much dilution would be a problem especially using such large second order groupings as Frazier and Kotlikoff propose, and there would have to be a "validation process" to combat the false negatives.

Frazier said the national protocol proposed could be a starting point for a discussion about how group testing could be done. Shrinking the pooled group size would logically reduce the inaccuracy rates, the researchers said, as would retesting any potential positive households, but both would also require much more testing.

For the group test plan to be effective, there also has to be an assumed limited base number of Americans who are thought to have the virus and who could be effectively identified by the mixing methodology.

Experts told ABC News group testing would only be efficient if fewer than around 20% of Americans are infected. Due to the believed prevalence of pre-symptomatic individuals with coronavirus, those with only mild symptoms, and asymptomatic people -- thought to be as many as 25% of all positive cases -- it's unclear how many people in the U.S. are currently infected.

Michael Kotlikoff, Laurence Kotikoff’s twin brother and Provost of Cornell University, acknowledged regulatory hurdles as well, since the available tests aren't designed or federally approved to be used by groups.

"This has not been approved by the FDA as a testing mechanism, despite the fact that it is a very well rounded scientific technique," Michael Kotlikoff said.

The FDA told ABC News it could not say if any test designers had approached the agency about gaining approval or authorization for group testing, other than the Nebraska study.

And finally, there's the matter of cost and the massive coordinated effort that would have to be undertaken to get test kits to and from every one of the 120 million American households and then run those tests in labs.

Laurence Kotlikoff said the investment still would be well worth it, considering the current economic crisis.

"The cost to all of this is trivial compared to what we're spending now with keeping the economy shut," he said. "People need to know that other people they go to work with or school with or restaurants with are virus-free and are safe to be around."

What to know about the coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

ABC News' Josh Margolin and Lee Ferran contributed to this report.