An explainer of a new marijuana-based pharmaceutical drug approved by FDA

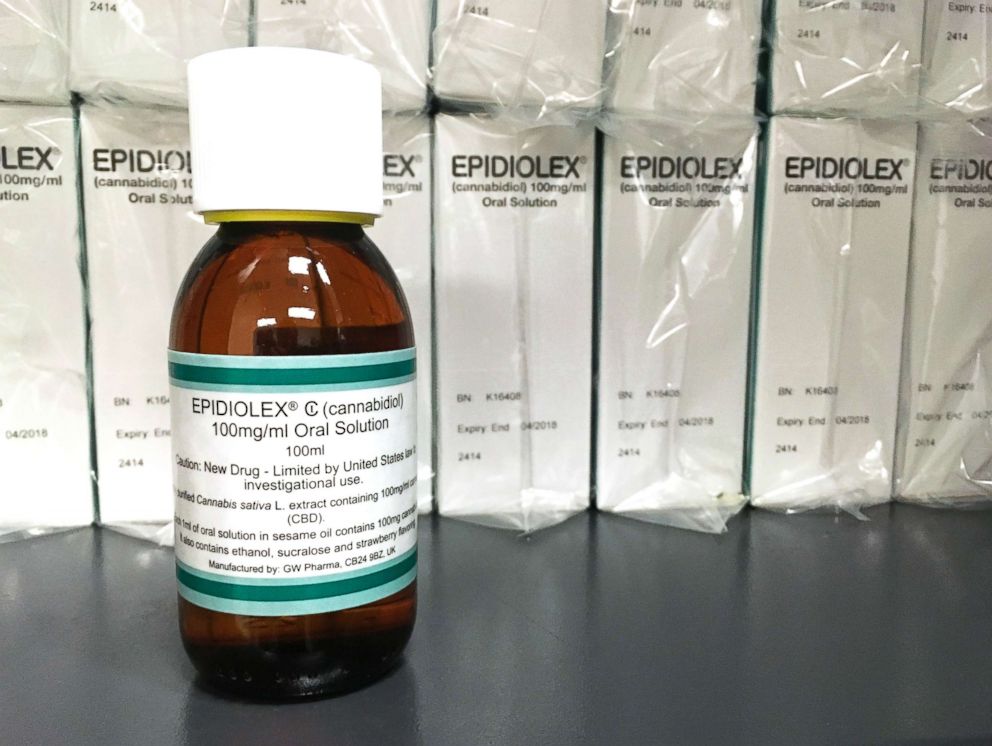

Epidiolex, a medication formulated from a cannabidiol (CBD) substance derived from the marijuana plant was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for children and adults over the age of 2. It treats Dravet syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome (LGS), two rare epilepsy disorders that primarily affect children.

What is Epidiolex?

Epidiolex is an oral liquid-based drug made from the cannabidiol (CBD) portion of cannabis. Compared to the tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) portion, CBD is not psychoactive, so taking this drug would not result in a high for the user.

CBD acts on different parts of the nervous system compared with THC. According to the Centers for Disease and Control (CDC), THC and CBD both may be useful for nausea caused by cancer treatments. Neither marijuana-derived substances, however, have been medically approved since they both fall under the Schedule 1 drug classification, which refers to substances that are usually illegal, often abused and have no proven medical benefit, according to the Drug Enforcement Administration.

Why was it approved?

The drug was approved by the FDA on Monday after a review of four large studies that looked at Epidiolex for the treatment of Lennox-Gastaut syndrome and Dravet syndrome in both adults and children.

The first major study looked at the effect of Epidiolex for Lennox-Gastaut syndrome was also published in The New England Journal of Medicine in May. In the study, the researchers enrolled 225 patients, ages 2 to 55 (all of whom had two or more seizures per day) to two different doses of Epidiolex or a placebo that contained no medicine. The trial lasted 14 weeks. The average seizure frequency dropped by 41.9 percent in the higher dose group and by 37.2 percent in the lower dose group and was down 17.2 percent in the placebo group (an inactive placebo often has a medicinal effect).

“We knew about the potential for CBD in seizure treatment for years, so we expected a response. Yet we were surprised at how robust the response was in this study,” Dr. Anup Patel, a pediatric neurologist at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Ohio and one of the lead authors of the study, told ABC News.

The second major study was published in The New England Journal of Medicine in May, and it looked at the effect of Epidiolex for Dravet syndrome. Researchers enrolled 120 children and young adults to compare Epidiolex to standard anti-epileptic treatment. After 14 weeks, the average seizure frequency dropped by at least half in 43 percent of people who took Epidiolex and 5 percent of the people taking the medication became seizure-free.

Both Dravet Syndrome and Lennox-Gastaut syndrome are diagnosed by a clinical exam and EEG by a doctor, ideally a doctor who specializes in brain conditions for children, known as a pediatric neurologist. Dravet Syndrome is confirmed with a genetic test.

What are the side effects of this medication?

In the trial, the main side effect was liver toxicity, which appeared as increased liver enzymes.

“Others may have felt more sedated, nauseous or experienced diarrhea or vomiting, but these were not life-limiting symptoms,” Patel told ABC News.

Dr. Nicholas Chadi, a pediatrician completing his fellowship at Boston Children's Hospital in pediatric and adolescent addictions, points to the limited research on CBD side effects in general.

“Only recently have we been able to separate CBD from THC, and to create substances with very high CBD content,” Chadi told ABC news. “So we don’t really know much about the effect of CBD on the developing brain or whether it could be addictive in the long run.”

Chadi noted there's significant research on the negative implications of THC, which is what produces the high in “weed” and affects the developing brain.

“There is some research that indicates that CBD specifically could interact with other medications such as statins, and increases the amount of those medications in the blood,” Chadi said.

When can parents of children with LGS or Dravet syndrome access Epidiolex?

The medication needs to go through several more steps before it's available as a prescription. First, the DEA will be moving towards de-listing CBD as a Schedule 1 drug. The pharmaceutical manufacturer behind the drug, GW Pharmaceuticals, is negotiating prices with health insurance companies. The process is expected to take 90 days, according to the FDA media briefing on Monday. ABC News also confirmed this expected timeline with GW Pharmaceuticals.

“We don’t expect to know the price until the fall, but over the coming weeks, we’ll work with setting a price with the insurance providers. We expect it to be covered by most insurers,” Justin Gover, the chief executive officer of GW Pharmaceuticals, told ABC News.

Can it be used for other epilepsy conditions in children and adults?

Not currently.

“The [pharmaceutical company] is also looking for other disease states for which the drug can help, but we don’t yet know what these are,” Patel told ABC News, adding that FDA approval means that it will be easier for the drug to be studied by other groups.

What should parents be aware of now?

All parents should be aware of unregulated CBD products on the market, an issue raised by both the FDA and Patel.

“We get at least one inquiry a day from patients either using, or considering using, CBD that they ordered online. The problem is these substances are not regulated, so it’s hard to know how to dose them. They may also be contaminated with other things, so the safety, particularly for children, is concerning,” Patel told ABC News.

“Patients should be having conversations with their physicians about these products,” FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb, M.D., cautioned. “As to whether this product provides them with the treatment they are looking for. These products haven’t been tested for safety and effectiveness.”

Overall, the approval is great news for parents of children suffering from Dravet syndrome or LGS, even if it will take at least three months before the medication hits pharmacy shelves.

“We are encouraging our patients to wait and explain to them why it’s a better way to go instead of using things that aren’t studied or tested," Patel said. "There is light at the end of our tunnel and soon we hope physicians can prescribe the medication for all patients in need."

Amitha Kalaichandran is a pediatrics resident at the University of Ottawa working in the ABC News Medical Unit in New York.