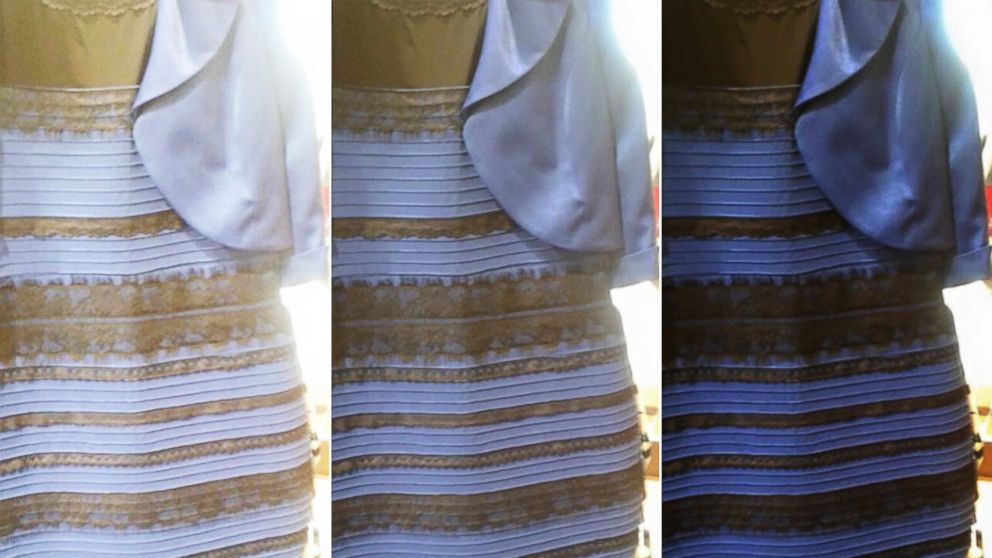

White And Gold Or Black And Blue: Why People See the Dress Differently

— -- Everybody, chill.

There's a scientific explanation for why #TheDress looks black and blue to some people and white and gold to the others.

(But seriously, it looks white and gold, amIRight?)

Although your eyes perceive colors differently based on color perceptors in them called cones, experts say your brain is doing the legwork to determine what you're seeing -- and it gets most of the blame for your heated debates about #TheDress.

"Our brain basically biases certain colors depending on what time of day it is, what the surrounding light conditions are," said optometrist Thomas Stokkermans, who directs the optometry division at UH Case Medical Center in Cleveland, Ohio. "So this is a filtering process by the brain."

Objects appear reddish at dawn and dusk, but they appear blueish in the middle of the day, Stokkermans said.

So we can recognize the same objects in different light conditions, our brains tweak the way we see things, he added.

"The brain is very good at adjusting and calibrating so you perceive light conditions as constant even though they vary widely," he said.

Colors can appear different depending on what they're near and the memory and past experiences of the beholder, Dr. Lisa Lystad, a neuro-opthalmologist at Cleveland Clinic’s Cole Eye Institute.

For instance, people who live in snow all year round above the Arctic Circle have several names for different colors of snow, but to most of us, snow is just snow. She said she has a turquoise purse that some of her friends swear is green and others are sure is blue.

Cataracts, colorblindness and eye disease can also alter colors for the beholder. Monet's famous water lily pond painting is thought to have been painted when he was developing cataracts, Lystad said.

But your perception of the dress doesn't mean you have an eye problem, she said.

"Vision just barely starts in the eye," Lystad said. "Your brain is what gives names to the colors."

David Calkins, a professor at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine and director of research at the Vanderbilt Eye Institute, said setting international color standards for everything from wires to fruits to paint pigments was a huge challenge before the digital age.

"There's no way for me to verify the color that your brain perceives versus the color that my brain perceives," he said. "What I call magenta, you might call violet. What I call burgundy, you might call purple."

And now that the digital age is here, there are subtle differences between how something can appear to you on a television screen versus a computer monitor versus a cell phone, Calkins said.