What to know about E. coli after the romaine lettuce-related outbreak

Just before Thanksgiving, a multistate E. Coli outbreak in the U.S. linked to romaine lettuce was reported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration. Because the government agencies had no idea where the dangerous food was being produced or sold, there was little they could report. The only recommendation was to cease all sales and consumption of romaine lettuce, and to dispose of leaves and heads of romaine immediately.

Now, the CDC and the FDA are advising that U.S. consumers not eat, and retailers and restaurants not serve or sell any romaine lettuce from central and Northern California. This updated recommendation comes as the CDC, FDA, and health officials in several U.S. states as well as Canada continue to investigate the multistate outbreak of Shiga toxin-producing E. coli illnesses linked to romaine lettuce.

The advice from the CDC remains: “If you do not know where your romaine lettuce is from, do not eat it.”

But the FDA is also rapidly changing their policy, and announced that it is taking steps to institute voluntary labeling of where romaine is grown.

“Romaine lettuce will be labeled with location information by region,” said the CDC in a statement. “It may take some time before these labels are available. When the labels are available, check labels or store signs for growing region before buying or eating romaine lettuce.”

Romaine lettuce harvested from regions outside of California’s northern and central growing regions, including lettuce grown in greenhouses or hydroponically, is not linked to this particular E. coli outbreak.

During this current outbreak, 43 people across 12 states have been reported ill. Sixteen were hospitalized, including one person who developed kidney failure from hemolytic uremic syndrome. No deaths had been reported. There are also reports that infections from this same E. coli outbreak have reached Canada, according to the CDC.

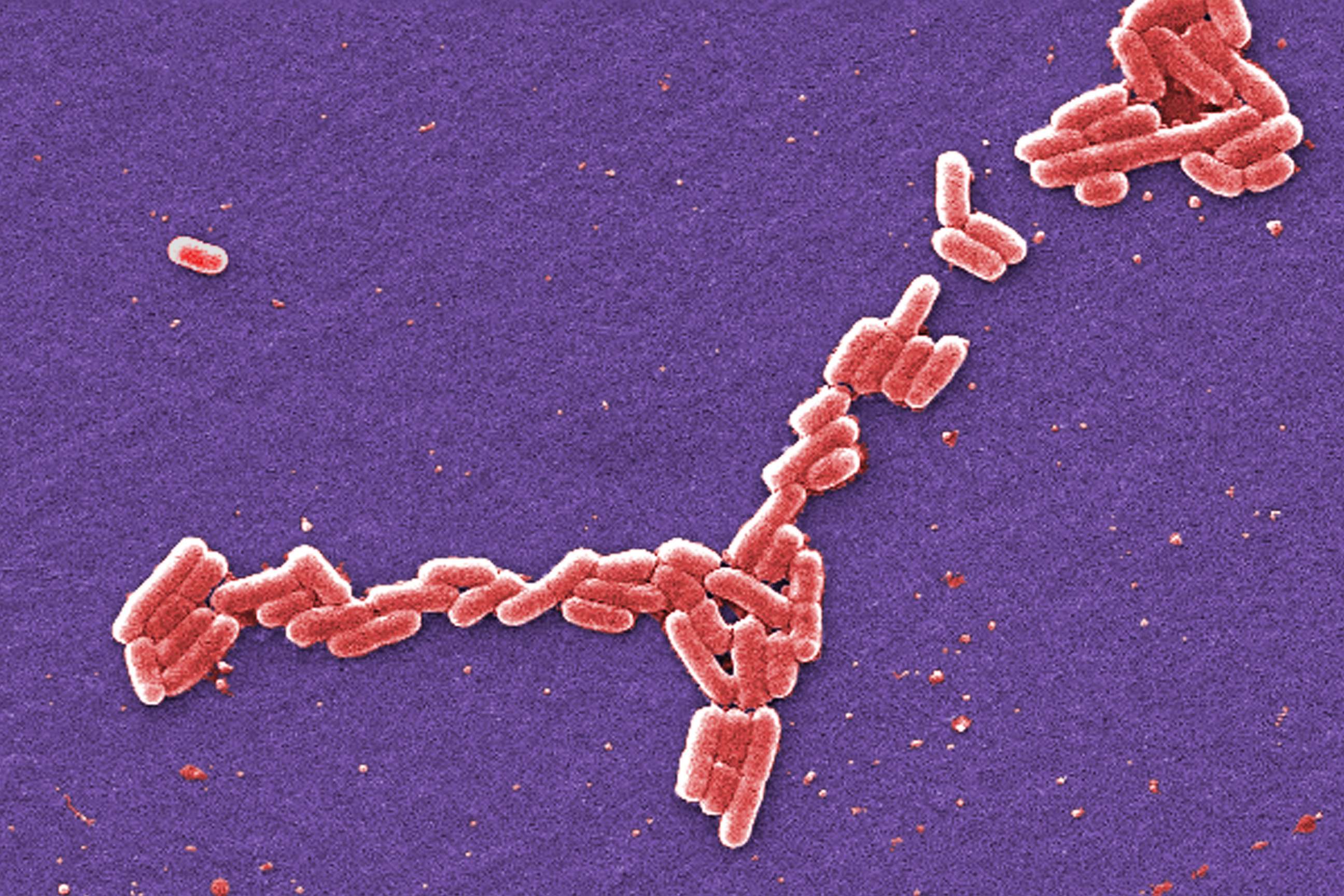

The bacteria on the lettuce is E. coli O157:H7, which is similar to a strain connected to an outbreak in the U.S. this past May. E. coli bacteria produces Shiga toxin, which can be deadly to humans.

What is E. coli O157:H7?

Escherichia coli, or E. coli, is a large group of bacteria that includes multiple strains, most of which are harmless and part of the normal flora of bacteria in the digestive tract.

Harmful strains of E. coli produce something called a Shiga toxin, which is harmful to humans. The most common strain of deadly E. coli in the U.S. -- the one linked to multiple outbreaks and fatalities over the past few years -- is E. coli O157:H7, which is often found in cattle. This strain has previously infected people through consumption of undercooked ground beef, and is best known for a deadly outbreak in 1992.

During the outbreaks in October and May of this year, however, the toxic strain of E. coli has been traced to romaine lettuce. No one knows how it was contaminated, and there is an ongoing CDC investigation.

Who is at risk?

People at any age are susceptible to E. coli infection, but very young children and the elderly are more likely to develop severe illness and complications.How does it affect people?

Symptoms of this kind of E. coli infection usually begin an average of 3 - 4 days after consuming the bacteria. The bacteria attach to the walls of the intestines and multiply, releasing the Shiga toxin. The symptoms include fever, stomach cramps, vomiting and diarrhea.

The good news is that most people recover in five to seven days as their immune systems kill off the troublesome bacteria. But between 5 and 10 percent of people develop a potentially life-threatening complication known as hemolytic uremic syndrome. This syndrome is associated with decreased urinary frequency, fatigue, and kidney damage. This has already occurred in one case associated with the October outbreak.

How to treat it

Since the illness is mainly due to the body’s reaction to the toxin produced by E. coli, antibiotics are not helpful for treatment. Some studies have even shown that taking antibiotics may actually increase the risk of developing hemolytic uremic syndrome. So the best advice is to treat it like any other diarrheal illness: drink lots of fluids (intravenous fluids for hospitalized cases), eat what you can, and get plenty of rest.

How to prevent infection

The first step is to avoid the source of the outbreak. The CDC recommends throwing out all romaine lettuce at home, even if you’ve eaten some of it and no one has gotten sick. This includes whole heads of romaine lettuce, baby romaine, and bags or boxes of pre-cut lettuce and salad mixes that contain romaine, including Caesar salads. Any lettuce of unknown origin should be thrown out, just in case.

Restaurants and retailers should take care to not serve or sell any salads that contain romaine lettuce.

If E. coli O157:H7 has somehow entered your kitchen, thoroughly wash and sanitize refrigerator drawers and shelves where the lettuce was stored. Wash your hands before you prepare food and again before you eat. Kitchens should be kept clean during food preparation as well. Though this outbreak is traced to lettuce, you can avoid other sources of E. coli by cooking meat thoroughly, avoiding unpasteurized dairy products and juices, and not swallowing water when swimming.

This article was written by Dr. Sunny Intwala on 5/3/18, and updated on 11/21/18 by Dr. Tiffany Yeh, an endocrinology fellow at New York-Presbyterian Weill Cornell Medical Center and a member of the ABC News Medical Unit.