New cervical cancer screening guidelines impact young women

The American Cancer Society released new guidelines for cervical cancer screening Wednesday, calling for "less and more simplified screening."

The biggest change is a recommendation to start screening for cervical cancer at age 25 instead of 21. One of the reasons is because vaccination rates have improved. In the United States, a common viral infection called HPV (short for human papillomavirus) is one of the leading causes of cervical cancer. But today, thanks to an effective vaccine that protects against the worst strains of HPV, fewer women are experiencing precancerous changes in their cervix in their early 20s.

"We definitely know the HPV vaccine is a great way to prevent getting HPV, which is the leading cause of cervical cancer, so it's almost like we're seeing the effect of the first domino not dropping," said Dr. Jessica Shepherd, an OBGYN at Baylor University Medical Center in Dallas.

The vaccine is available for men and women. Since HPV is a sexually transmitted infection, the vaccine is recommended for both sexes.

If left undiagnosed, HPV can cause more problems for women, leading to precancerous changes in the cervix.

As of 2018, 39.9% of adults ages 18 to 26 (53.6% of whom were women) reported having received at least one dose of the three-dose HPV vaccine schedule. 51.1% of men and 68.1% of women ages 13 to 17 had at least one dose of the vaccine. The authors of the guidelines wrote that they expect the HPV vaccine "to have a substantial impact on cervical cancer screening strategies and outcomes in coming years."

There are other reasons to support moving the age of the virus screenings up to 25. Cases of invasive cervical cancer in women between 20 and 24 years of age are rare. In addition, most HPV infections in this age range become undetectable in one or two years.

All told, doctors at the American Cancer Society concluded that the possible harms associated with screening women ages 21 to 25 outweighed the possible benefits.

The authors of the guidelines explained that "there are also potential harms related to the treatment of precancerous cells identified by screening -- including premature birth. And screening has not been shown to lower the rate of cancer in women in this age group."

Dr. Jennifer Ashton, an OBGYN and ABC News chief medical correspondent, said, "We have a good understanding of the natural history of HPV as it relates to causing cervical cancer: It is generally a very slow process that occurs over 10 or more years. We also have learned that performing unnecessary surgery on the cervix to remove a lesion that often resolves on its own, has significant risks, especially when performed on women of childbearing age."

The guidelines also recommend doctors start testing for HPV infection at age 25, and every five years thereafter. This is a big change, as the guidelines previously stated testing should start at age 30.

The new guidelines explain that an estimated "13% more cervical cancers and 7% more cervical cancer deaths" could be prevented by moving the age of HPV testing from 30 years to 25 years.

There are three ways to screen for cervical cancer: Doctors can use an HPV test, a Pap test or a combination of the two, referred to as "cotesting."

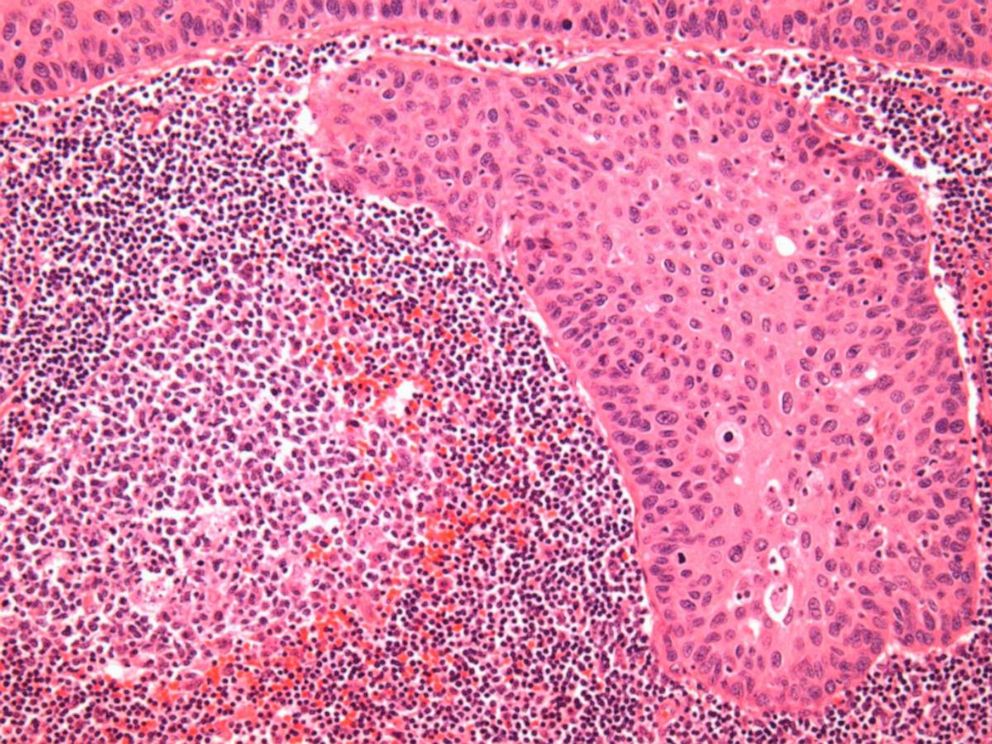

HPV and Pap tests are often performed together because they both entail a pelvic exam. With a Pap test, cells are observed under a microscope to detect abnormal changes, but an HPV test looks for the presence of the virus itself.

There has been a debate in the medical community about which of the three ways is best for screening. Many believe that cotesting is better at catching cancer than HPV testing alone. The new guidelines by the American Cancer Society recommend only testing for HPV, and conducting no Pap tests at all.

"I still believe [the] Pap and HPV [tests] are both necessary," said Dr. Shepherd.

A study published earlier this month found cotesting was more effective than HPV or Pap tests alone, and the Pap test caught more cases of cancer than the HPV test. The National Cancer Institute at the NIH said that both HPV testing and cotesting are more efficient than Pap testing alone.

Regardless of which test is used, experts say young women shouldn't take the new guidelines to mean they get a free pass to avoid going to the gynecologist for a few more years.

"If you don't have women coming in until they're 25, is there going to be a four-year gap to when patients actually see their gynecologist? Really there are so many other things to talk about at the well-woman visit, which include contraception, sex education, STD testing, family planning and many times people assume, 'If I don't need my pap, I don't necessary need to go to the gynecologist,'" said Dr. Shepherd.

Ashton added, "It is critical to realize that not getting cervical cancer screening every year does not mean a woman should not see her OBGYN for well-woman care. As primary care physicians for women, we address hormonal issues, screen for depression and heart disease risk factors, address bone health, sexual function, breast conditions and abnormalities of the ovaries and uterus as well. We treat the whole woman, not just a body part."

There are multiple organizations that review research and put out guidelines for cervical screening, which differ from these new guidelines. One well known organization is the United States Preventive Services Task Force, which last updated their guidelines in 2018.

Ultimately, it's up to each patient's doctor to suggest when the best time is to screen said patient for cervical cancer.

"It's the responsibility of the practitioner to discuss the latest guideline updates to help patients understand why that's changed and then let the patient decide for themselves, with autonomy, how they would like to proceed," Dr. Shepherd said.

If you have been diagnosed with cervical cancer or pre-cancer, these guidelines do not apply. The American Cancer Society recommends "these women should have follow-up testing and cervical cancer screening as recommended by their health care team."

"Cervical cancer could be eradicated within our lifetime in the United States if we do it right," said Dr. Alexi Wright, the director of gynecologic oncology outcomes research at Dana-Farber. "It requires increasing HPV vaccination rates, regular screening, early diagnosis and new therapeutics. But the most critical steps are boosting vaccine rates and screening. The American Cancer Society's screening guidelines are an important step in defining who should be screened -- and how -- to improve outcomes."

"We need to make sure that we're taking an approach to women's health that is inclusive of the entire patient-doctor relationship and experience, rather than just the testing." said Dr. Shepherd.

Sabina Bera, M.D., M.S., a psychiatrist in New York, and Molly Stout, M.D., a dermatology resident at Northwestern in Chicago, are contributors to the ABC News Medical Unit.