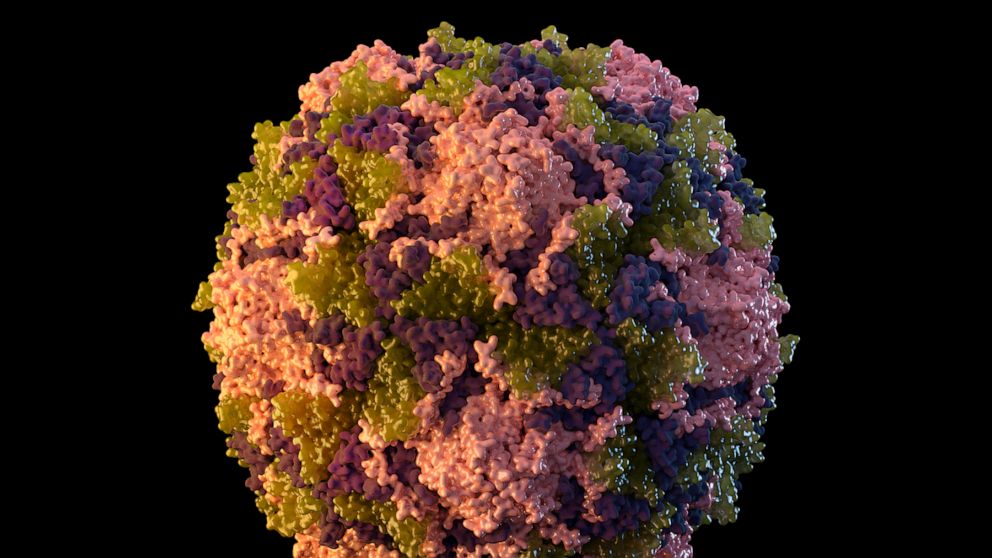

How a case of polio appeared in the US and who may be at risk

This is a MedPage Today story.

It had been nearly 10 years since a case of polio was detected in the United States. Now, infectious disease experts are breaking down what could have led to the new case in a Rockland County, New York, resident and what may be the level of threat to others moving forward.

The case in Rockland County has been reported to be in an unvaccinated adult man from the Orthodox Jewish community. An outbreak of measles in New York in 2018 and 2019 primarily affected the same community.

While posing essentially no risk to the broader population at this point, there is public health concern for Rockland County because the individual appears to be part of a religiously conservative community that often avoids vaccination, Dr. William Schaffner, a professor in the division of infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, told MedPage Today.

The concern is that there could be other cases that occur there. Though measles is a respiratory virus and polio lives in the intestinal tract, "both of them are spread rather readily," Schaffner noted.

There is the potential for secondary spread of the polio virus beyond Rockland County, such as if an infected individual traveled to another unvaccinated community, Schaffner acknowledged. "But we're not there yet," he said.

How it happened

The last case of polio detected in the U.S. was in 2013 in a person who contracted it abroad. The last case to originate in the U.S. was in 1979.

So, how did the disease reappear?

The New York State Department of Health announced regarding the Rockland County case that sequencing performed by the state's public health laboratory and confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed revertant polio Sabin type 2 virus, indicative of a chain of transmission involving the oral polio vaccine, which is no longer used in the U.S.

Schaffner explained to MedPage Today how such a chain of transmission could occur.

For the oral vaccine, the polio virus is altered in the laboratory, so that it is "tamed." The immune system reacts to that weakened virus to generate protection in case of future exposure to polio, he said.

"However, on every sunny day a little rain may fall," Schaffner said. "Somewhere during this process, the polio virus that was tame, mutated and reverted back to a virus that could actually create the illness polio. This was a limitation, albeit a very rare one of the oral polio vaccine. It occurs about once every 3 million doses."

What likely happened in the case of the individual from Rockland County, who had not traveled to another part of the world, is that someone visited their community and brought with them in their intestinal track this polio vaccine virus, Schaffner said.

"Somewhere along that chain it mutated back to a bad virus," he said.

What's the risk level?

Dr. Jan Patterson, an infectious disease physician with UT Health San Antonio in Texas, told MedPage Today that the virus is primarily transmitted via the fecal-oral route, although it can possibly be transmitted by respiratory droplets as well. Washing of the hands after using the restroom can help address microscopic fecal material left on the hands.

The Rockland County patient has been noted to have some form of paralysis. "Depending on where the virus localizes in the spinal cord, it can be life threatening," Schaffner said.

Schaffner explained that, in such a case, the mutated polio virus would have moved out of his intestinal tract, traveled to his spinal cord and infected certain cells, resulting in some paralysis that is likely to create a degree of long-term disability.

"This is an extraordinarily rare event," Schaffner said, also noting that other countries around the world are gradually transitioning from oral to injectable polio vaccines.

"The really sad thing about this is, this gentleman's infection...could have been completely prevented if he had been vaccinated," Schaffner said.

As far as containment measures, Patterson said that New York is doing the right thing with a vaccination drive, attempting to get those who are unvaccinated in the affected community vaccinated.

It's also important for people who are unvaccinated to get vaccinated as soon as possible, Patterson said, because a first dose can "take a while for the immune system to get revved up."

Though cases of polio in the U.S. are rare, one concern is that "there are many children who are not getting vaccinated these days because of this anti-vaccine movement," Patterson noted. "They are really at risk if this does take off."

Children are also especially susceptible, she said, due to poorer hygiene practices that can result in fecal-oral spread.

In Rockland County, public health experts undoubtedly "are trying to be persuasive, helpful, offering vaccination in that community," Schaffner said, "because there will be other people in that community who are not vaccinated against polio."

Encouraging vaccination may not be an easy task, he conceded, especially if individuals have a firm belief tied to a religious faith.

In the case of the recent measles outbreak, children who were unvaccinated were excluded from school, he noted. That measure can be persuasive, though not entirely so.

"There is the potential for this now-reverted virus to spread in that community," Schaffner said. "If it can do that, there could indeed be more cases."

Local providers are urged to be alert to polio as a potential cause for any patients presenting with difficulty in movement but also for the minor symptoms the virus can present with -- diarrhea, abdominal pain, fever -- which can mimic any number of intestinal viruses common in the summer months, he said.

"This is a matter of great interest, even though it is one case," Schaffner said. However, "the general population," he said, "is extremely well protected through our routine polio vaccination campaign."