Breast cancer disparities: Black women more likely than white women to die from breast cancer in the US

To mark Breast Cancer Awareness Month, we’re sharing stories of breast cancer journeys.

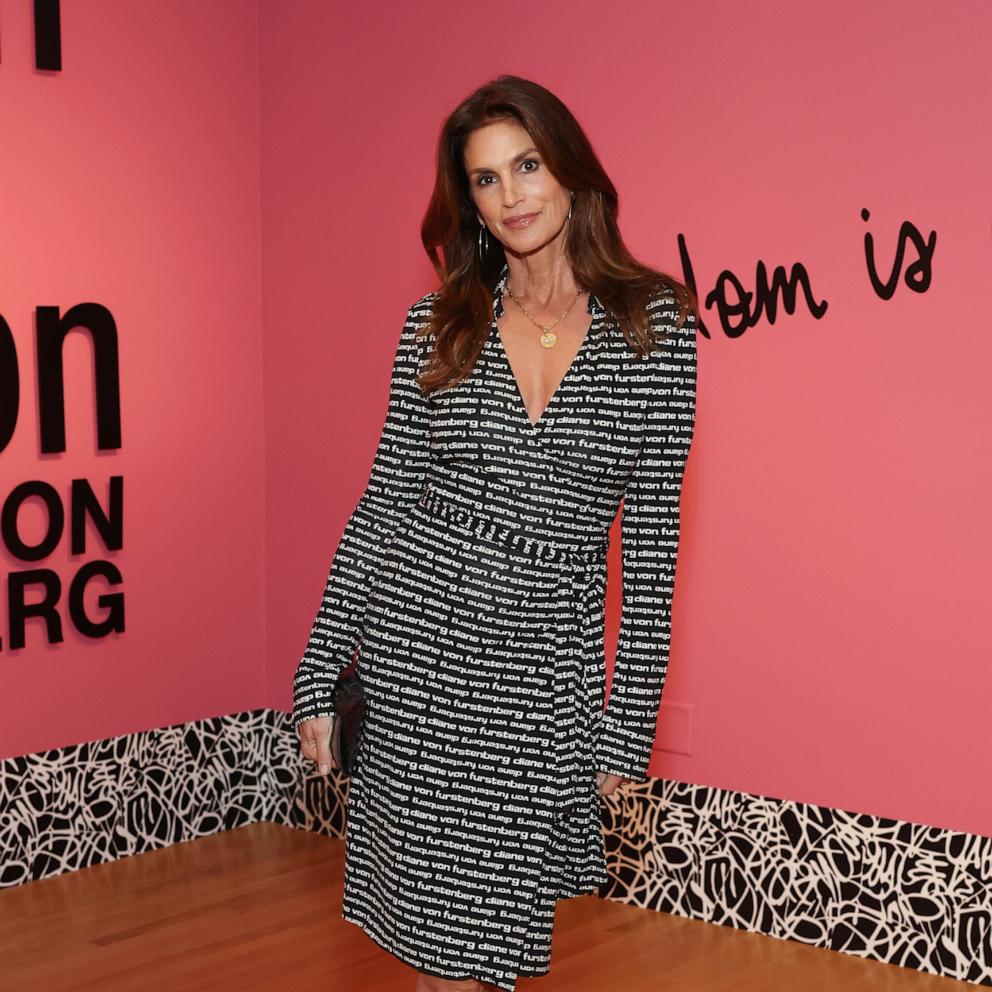

For Breast Cancer Awareness Month last year, tennis star Serena Williams went topless in a music video, singing the song "I Touch Myself" while covering her breasts with her hands. It was all to remind women about the importance of regular self-check breast examinations and being aware of any changes.

"Yes, this put me out of my comfort zone," Williams, 37, wrote on Instagram. "But I wanted to do it because it's an issue that affects all women of all colors, all around the world."

In reality, breast cancer disproportionately affects some groups in the U.S. more than others. The death for black women of breast cancer from 2012-2016 was about 40% higher when compared to white women, according to the American Cancer Society, which cites more advanced stages at diagnosis, higher prevalence of obesity, chronic illness and other unfavorable tumor characteristics.

Despite similar incidences of breast cancer between white and black women in the U.S., black women often suffer from the disease at younger ages and are more likely to die from their disease at all ages. This disparity was first recognized thirty years ago in statistics from the National Cancer Institute, and it's one that persists today.

In September, the American Association for Cancer Research released their Cancer Progress Report highlighting the ongoing challenge of disparities faced in cancer care. Despite new advancements in earlier detection and therapy, and with an overall decline in cancer deaths by 39 percent in the 26-year lead up to 2015, it’s perplexing that some American women don’t fare as well as others in breast cancer outcomes. What exactly accounts for these differences?

Like many big questions in medicine, the answer is complex. Some of these factors may be genetically driven, and many of them may be related to larger social and structural institutions. Here we break down the major factors.

Possible differences in cancer biology

As Williams points out and as is generally true for all cancers, the earlier breast cancer is caught the better. This is based on the understanding that catching a cancer when it is localized (just in the breast), before it has had the chance to spread, leads to much better outcomes. For example, localized disease treatment boasts a 99 percent survival rate five years after diagnosis, versus only 27 percent in distant, metastatic forms of the disease.

This idea itself may come as no surprise, but what is astounding is that black women have more incidences of breast cancers that have spread than white women, even though black women have comparable rates of breast cancer screening via mammography. Although some believe that the data overestimates mammography rates in minorities and especially the elderly, people are looking at other explanations for these differences beyond screening.

One thought on why black women may have worse breast cancer outcomes is rooted in a difference in genes. Although breast cancer is seen as one disease, there are so many subtypes. Scientists are getting better at recognizing through genetic detection, which cancer type a woman has, and each of these subtypes likely has different risks and different outcomes. They also respond differently to therapy.

Scientists are trying to look closely at the different genetic make-up of cancer cells to understand whether biology is at play in determining the different outcomes in American communities. While the genetic evaluation of cancers is only in its infancy, there are some things we already know. It is well-documented that black women are much more likely than white women to have triple negative breast cancer. This is a type of cancer that is not responsive to three of the most common hormones that usually cause breast cells to grow – estrogen, progesterone, and human epidermal growth factor – and is notoriously more aggressive and difficult to treat.

Yet, the link between genes, the environment, and disease is complicated and often a game of chicken or the egg. It’s been shown that a number of risk factors—-such as diet, socioeconomic status, body mass index and pregnancy history–-also affect breast cancer incidences and outcomes, leading some to wonder whether these factors in turn play into genetics.

But the fact that racial disparities can be geographically mapped in communities known to be poorer and more segregated has clued many to the fact that the differences in cancer outcomes can’t be attributed to molecules alone.

Structural systems at play

Understanding breast cancer disparities in America requires an appreciation for the larger structural inequalities that exist and their wide-ranging effects, from varying health care behaviors to health care access to disease burden.

Racial inequalities at a social level have shaped systems in huge ways. Access to safe housing, transportation, quality education and jobs, as well as the availability of fresh fruits and vegetables are all elements of daily life that run along racial and economic lines in the U.S.

Poverty can bring with it a host of bad health outcomes and diseases, including obesity, which can negatively influence a woman’s breast cancer landscape. Studies have shown that economic status explains much of breast cancer outcome disparities. Black women suffering from breast cancer are more likely to have other medical conditions, which can complicate their disease.

Lowered socioeconomic status has also been associated with a lowered rate of receiving recommended chemotherapy and radiation. This may be due to a lack of access to care, for example either because of health insurance or no transportation. States and cities that have made improvements in insurance coverage have seen a narrowing of breast cancer disparities between black and white women.

Over the last several decades, there have been fewer studies in breast cancer research looking at black women. Even now, minority communities are less likely to be involved in cancer trials that will be shaping future approaches to treatment.

Where to go from here

The first step in addressing the problem is recognizing that disparate outcomes between races is an issue in the U.S. Doctors, scientists, and national agencies are now committed to discussing and eliminating disparities in breast cancer outcomes.

The reasons why breast cancer disproportionately affects black women in the U.S. rest in a complicated intersection between genetic and social factors. Further research and attention should bring nuanced interventions from multiple angles, including ongoing investigation into genetic therapies and research into the way that social forces continue to shape health outcomes.

Amisha Ahuja is an internal medicine resident at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital and a contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit.

This report was originally published on October 16, 2018.