Breakthrough COVID-19 infections and deaths rose during delta, but far outpaced by the unvaccinated

As Americans brace for the possibility of another difficult winter ahead in the nation’s fight against coronavirus, there is a renewed sense of urgency to get as many people inoculated and boosted as quickly as possible, given the emergence of the highly contagious omicron variant -- now dominant in the U.S.

An ABC News analysis of federal and state data found that since July, there has been an acceleration of the number of breakthrough coronavirus cases, thus, of individuals who test positive after being fully vaccinated.

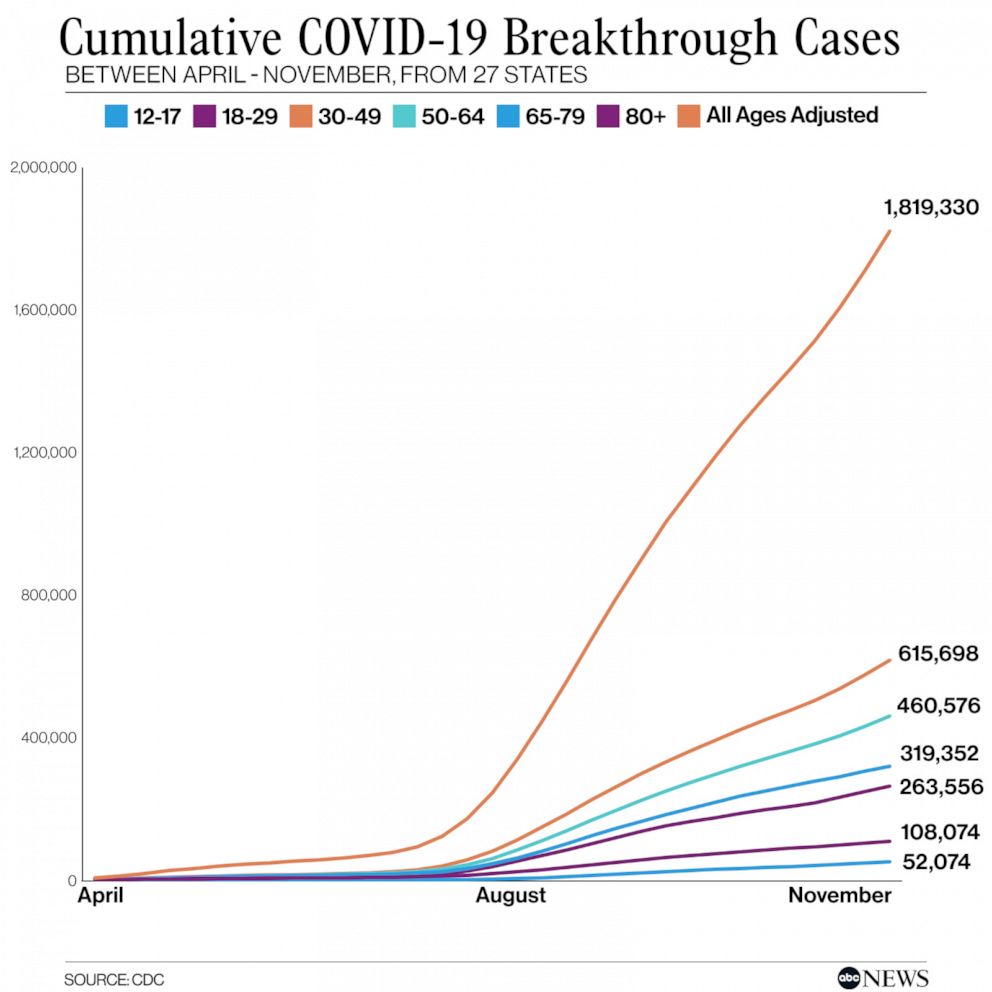

While federal data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is incomplete, only accounting for a subset of states, the analysis found that between April and November, more than 16,700 vaccinated people had died -- the vast majority since the start of the delta variant's surge, earlier this summer. Similarly, nearly all – approximately 96% -- of the 1.8 million breakthrough cases – have come during the same time period.

Comparatively, in those select states, at least 5.8 million unvaccinated Americans had tested positive, and just under 64,000 unvaccinated Americans had died, during the same time period.

Despite the increase in coronavirus infections among vaccinated people, experts say vaccines are holding strong in their ability to dramatically reduce the risk of severe illness.

"Just because you have a breakthrough infection doesn't mean the vaccine does not work and isn't giving you huge benefit,” Dr. Justin Lessler, professor of epidemiology at University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, told ABC News.

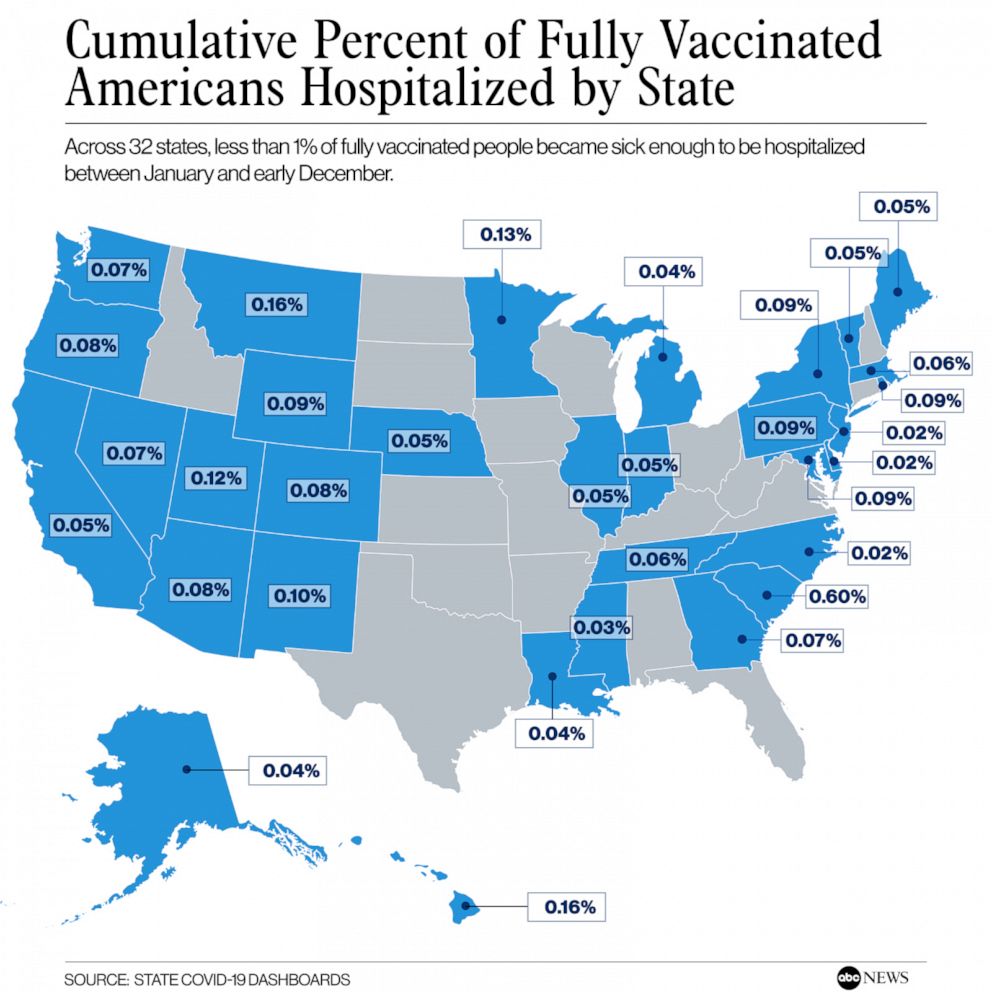

The analysis of state data reveals that the percentages of fully vaccinated individuals testing positive, requiring hospitalization, or dying of coronavirus remain quite low when compared to the percentage of unvaccinated Americans experiencing severe illness because of the virus. Since the rollout began last winter, only a small fraction of fully vaccinated people in the United States have experienced a breakthrough infection, and an even smaller percentage have been hospitalized or died.

"I think if you look at the data, it's clear the vaccine is working," Lessler said.

Breakthrough infections captured by the available data have been predominantly still associated with the delta variant. However, as concerns grow over the potential impact of the omicron variant, preliminary data suggests the new variant may be more likely to cause infections among vaccinated people.

Breakthrough cases becoming more common, data shows

Many vaccines lose their power over time and are not nearly as effective even initially as the COVID-19 vaccines. The tetanus vaccine, for example, requires a booster shot every 10 years. Other vaccines, like the flu shot -- which, according to the CDC, reduces the risk of flu illness by between 40% and 60% among the overall population -- are needed on a yearly basis.

When the COVID-19 vaccines were first launched last December, experts did not know how long their protection would last and how the evolution of the virus might impact vaccine efficacy. At the time, Pfizer and Moderna both estimated that their vaccines were more than 90% effective.

By late May, several weeks after the vaccine program became open to the general adult population in mid-April, about half of Americans had been fully vaccinated against COVID-19. But in the summer and fall, as the highly-transmissible delta variant became dominant, the nation began experiencing a marked increase in infections, including among vaccinated people, as the efficacy of the vaccines began to wane.

“We do have some evidence of vaccine effectiveness waning a bit,” Ellie Murray, an assistant professor of epidemiology at Boston University School of Public Health, told ABC News. “Vaccinated people start to have a higher chance of being infected than they did closer to the date of their vaccine.”

However, reporting from health officials and data revealed that infections in inoculated individuals tended not to be severe, thanks to underlying protection from the vaccines against acute illness.

CDC data, sourced from more than two dozen states, shows that between April and June, a total of 77,000 breakthrough cases and 1,500 breakthrough deaths were recorded, compared to more than 1.74 million breakthrough cases and 15,000 deaths recorded between July and the first week of November. It is unclear exactly how many of these people had also been boosted.

The federal data was pulled from 27 states, which regularly link their case surveillance and immunization information.

State-level data for breakthrough COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations and deaths is not publicly available in every state. But data obtained by ABC News from 41 states -- which extends to December -- echoes findings from federal data that even though the acceleration trend in breakthrough infections has continued over the last two months, the percent of fully vaccinated Americans who have experienced a breakthrough case remains low.

“An important thing to think about with breakthrough infections is not simply the number of [breakthrough cases], but what percentage of people who are vaccinated are having breakthrough infections and whether that percentage is changing in a meaningful way,” Murray explained.

Like the federally compiled data, state-level data from January to December also shows that infections among vaccinated people were still relatively uncommon. Meanwhile, it remains exceedingly rare for a vaccinated person to die of COVID-19.

Data for breakthrough infections, cases, and hospitalizations varies greatly by state. Some states provide data for all three variables, while others only offer statistics for one or two variables.

Data from 36 of the states showed that approximately 1.37% of those fully vaccinated have experienced a breakthrough infection between January and December. Similarly, data from 34 of the states showed that about 0.05% of those fully vaccinated Americans have experienced a breakthrough case that required hospitalization, and data from 36 states showed only 0.01% of those fully vaccinated have died of COVID-19.

In October, unvaccinated individuals had a 5 times greater risk of testing positive for COVID-19 and a 14 times greater risk of dying from it, as compared to fully vaccinated individuals, according to data compiled by the CDC. Additionally, unvaccinated individuals had a 10 times greater risk of testing positive for COVID-19 and a 20 times greater risk of dying from it, as compared to fully vaccinated individuals with a booster.

Breakthroughs do not mean vaccines are not working, experts say

With more people getting vaccinated, and protection declining over time since the initial vaccination series, breakthrough cases are to be expected, experts concurred.

“With waning immunity, new variants and increased population mobility, it’s no surprise that we are seeing a surge in breakthrough cases. While breakthrough cases will be for the most part mild or even asymptomatic, any new case only furthers community transmission and prolongs the pandemics,” said John Brownstein, Ph.D., an epidemiologist at Boston Children's Hospital and an ABC News contributor.

Although vaccines remain overall, “very, very effective,” and “extremely effective” against hospitalization and death, there does indeed appear to be a decline in protection against infection, over time, Lessler explained.

“Even if we're seeing a lot of breakthrough infections, those people are going to be less likely to end up in the hospital clinic compared to somebody who is [unvaccinated],” Lessler added.

Murray and Lessler both likened the COVID-19 vaccine to a seatbelt, explaining that even if an individual were to get into a car accident, the seatbelt can often, but not always, help prevent significant injury or death.

“Breakthrough infections are not evidence that vaccines don’t work anymore than the fact that car crashes [that] are still sometimes fatal is evidence that seatbelts don’t work. We use prevention tools because they help reduce our risk of serious disease or death, not because they are guaranteed to 100% always keep us safe,” Murray said. “If we held to that latter standard, we’d never use any preventive measures because nothing is perfect, and the result would be much more death and disease and disability.”

According to data from Peterson-Kaiser Family Foundation's Health System Tracker, from June to September, the large majority of breakthrough hospitalizations affected older Americans, as well as those with comorbidities. Further, their average stay at the hospital was shorter than those who were unvaccinated.

The unknown of omicron

Over the last three weeks, concerns over omicron have rapidly traversed the globe. Data from the CDC shows that in the U.S., the presence of the omicron variant, now the dominant variant domestically, has increased by 70% over the last two weeks.

“With omicron displaying increased transmissibility, breakthrough cases will unfortunately become even more normalized,” Brownstein said.

Experts concurred that although much is still unknown about the omicron variant, it could also potentially cause more breakthroughs than past variants.

“Omicron is going to be more than a major player. It is going to be the main story,” Lessler said, adding that the U.S. may see a significant wave of infections, which could cause significant systemic challenges for hospitals.

Preliminary data suggests that omicron not only spreads at a rate two to three times faster than the delta variant, but also, may be more likely to cause infections among vaccinated people. Despite this, vaccines and additional booster shot protection still appears to dramatically reduce the risk of severe illness.

Ultimately, personal responsibility will play a major role in preventing additional spread, experts agreed.

Boosters and vaccines remain the key to slowing the spread of the infections, and ultimately to turning the pandemic around, particularly when combined with social distancing, masking and other preventative measures, according to the CDC.

“We have the right tools to limit breakthrough cases. Testing before traveling or attending a gathering can help prevent risk to both vaccinated and unvaccinated people. Similarly, boosters when eligible can dramatically reduce the risk of transmission,” Brownstein said.

The CDC currently recommends that everyone ages 16 and older receive a booster shot six months after their Pfizer or Moderna vaccines or two months after the Johnson & Johnson shot.