Boosters are the best defense against omicron. But that message isn't getting through.

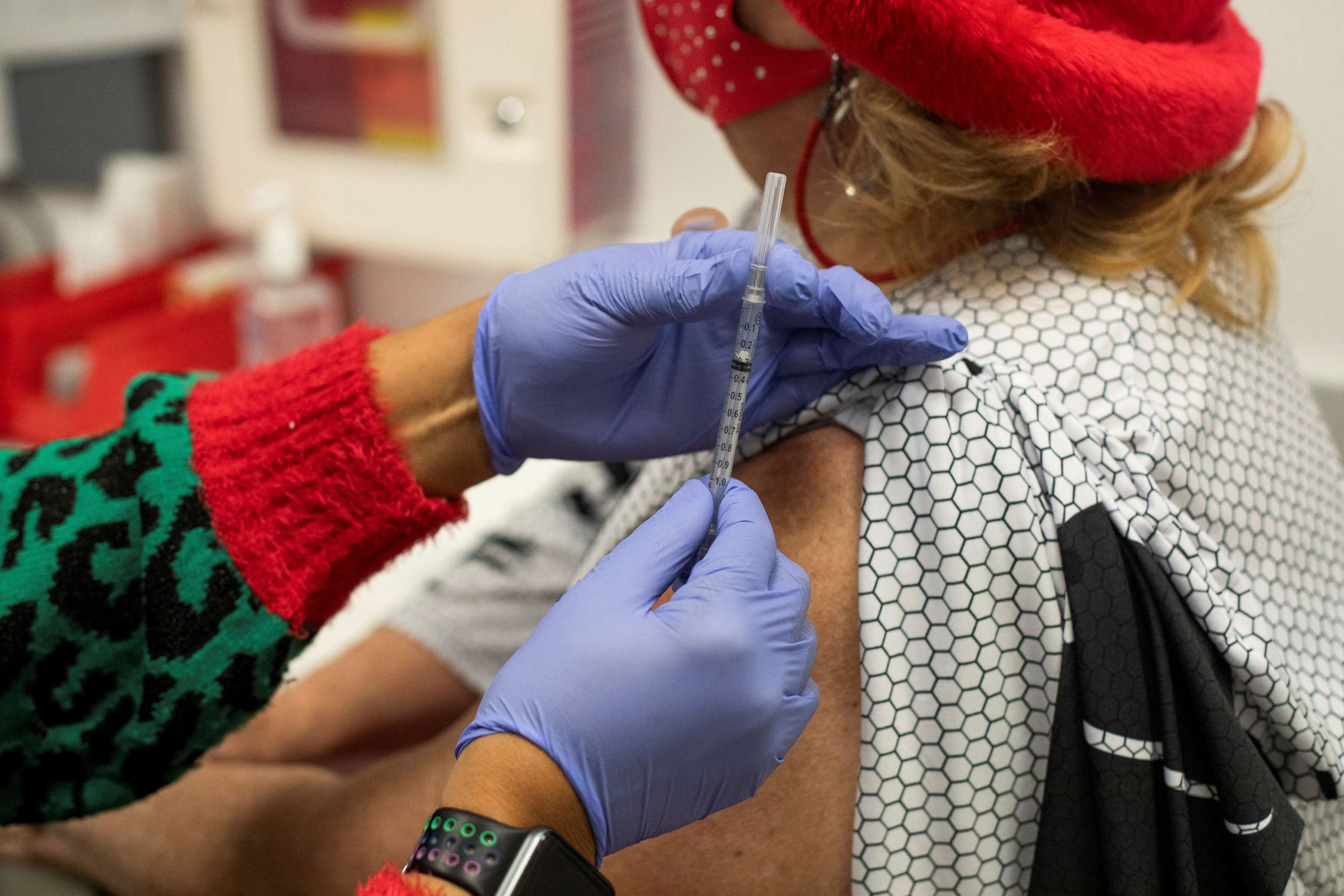

For weeks now, as public health experts have warned about the COVID-19 omicron variant and its incredible ability to infect people, they've followed the bad news with good: booster shots available to every adult in the U.S. drive protection against omicron back up.

One of a few glimmers of scientific optimism in the omicron era is that the variant can be held at bay or kept to a very mild infection when people get a boost. And yet, just 4 in 10 eligible Americans have gotten a booster shot.

Among the most vulnerable Americans -- those over 65 years old -- it's slightly higher, but still low: Just over 60% have gotten their booster shots, according to White House data presented last week.

Despite the demand for other pandemic tools, like at-home rapid tests or new treatment pills from Pfizer and Merck, many experts point to booster shots as the best method to actually prevent sickness -- and they've been there, widely available, for weeks.

"The booster is exponential. It's not just a little bit different. It's a lot different," said Janet Hamilton, an epidemiologist and the executive director at Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists, a group that works closely with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

"I don't know that we have really communicated that effectively enough for people to say, 'I really need to get this, this is a big deal,'" she said.

Why are the rates so low?

Public health directives can take a long time to circulate and have historically reached marginalized populations even slower.

But when it comes to boosters, that message was particularly muddled.

"The recommendation for the booster has come out in bits and pieces, and the most recent recommendation for everyone to get a booster is pretty new still," Hamilton said.

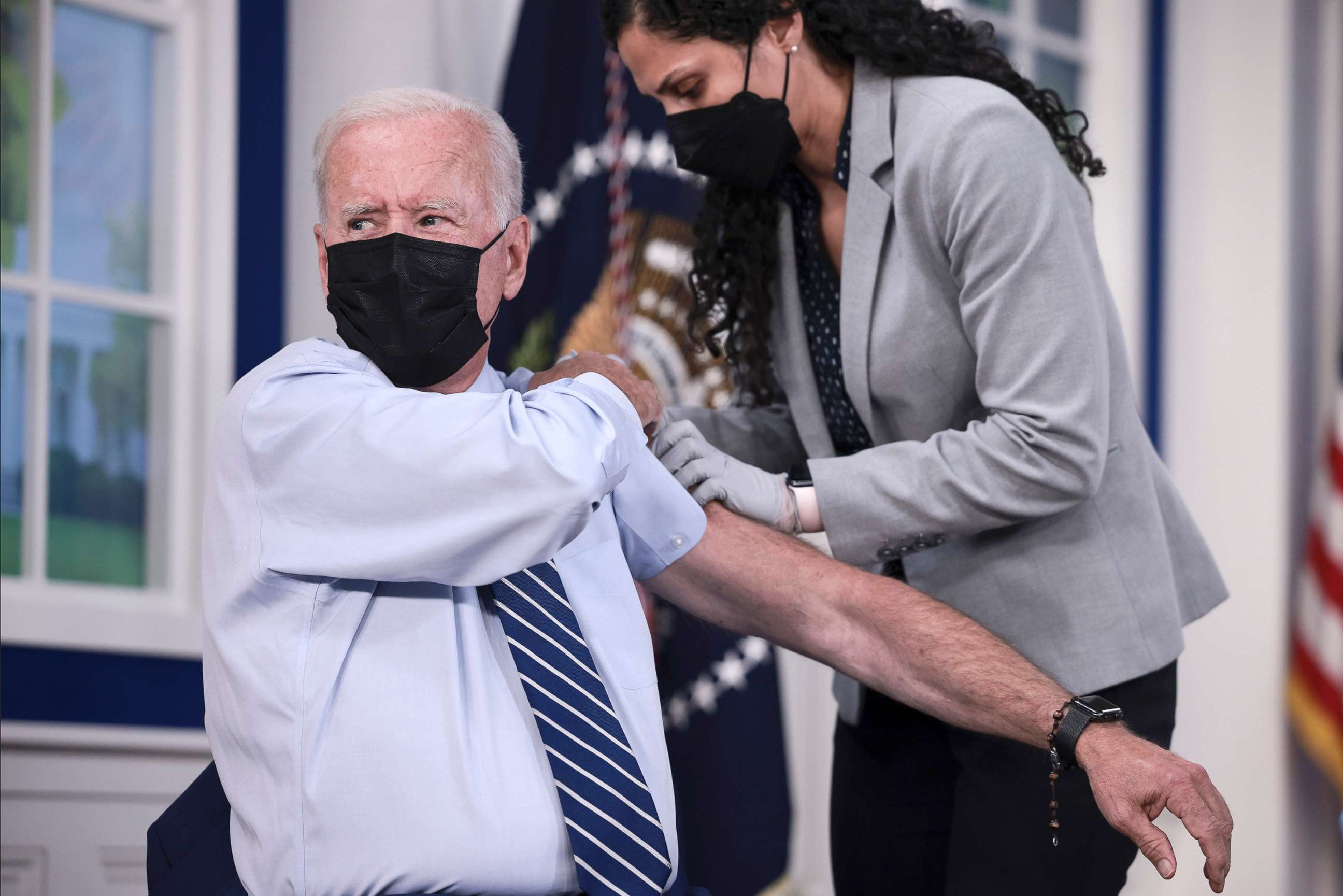

The confusion began after President Joe Biden and his administration called for boosters for everyone eight months after their second dose. But experts at the CDC and Food and Drug Administration didn't jump onboard, instead spending the summer months debating if there was a need for boosters for the whole population or only the most vulnerable.

By the time boosters were recommended in November -- a recommendation that applied to all adults who'd been fully vaccinated for six months -- the data was strongly backed by most in public health.

But, as Hamilton noted, "it takes time for people to hear the information."

Unfortunately, the country didn't have the luxury of time. It took just a few weeks for omicron to gather steam in the U.S. By Dec. 18, it was nearly 75% of all cases in the U.S., and nearing 90% along the East Coast and Midwest, the CDC found.

And because the variant evades vaccine immunity -- whittling down protection from the first shot to somewhere between 30-40%, according to a study out of the U.K. -- the booster shot, which brings protection up to nearly 70-80%, became an urgent public health missive.

Among nursing home residents

In nursing home patients, the CDC released data last week that showed the highest COVID cases were among the unvaccinated, but cases were also increasing among fully vaccinated patients without a booster.

Meanwhile, fully vaccinated and boosted nursing home patients had a 10 times lower rate of getting COVID, the CDC found.

"We're sitting on an enormous vulnerability right now," said Dr. Ali Khan, a primary care physician in Chicago and executive medical director at Oak Street Health, a primary care network.

Khan, who also treats patients at nursing homes, said he thinks omicron has shed new light on booster urgency — but only in certain areas.

"I think it's leading to increases in booster enthusiasm around relatively privileged populations," he said.

"But we have a lot of work to do in people receiving those messages like nursing home residents, like minority communities that may have had more complex reactions to vaccines in the first place, to really say, 'Hey, this is super crucial'," he said.

Disparities in messaging

Dr. Jay Bhatt, an internist also practicing in Chicago and an ABC News contributor, said among his patients on the city's Southside, largely low-income people of color, the reasons about half have rejected a booster shot is because of "changing messages."

Patients say they "lost trust in government," and the different timelines on when to get a booster led to feelings that it was optional.

"They feel like they can wait longer before they get it," Bhatt said.

But the doctors noted that the same investments the country made in the initial vaccine rollout can be made on boosters, with positive results.

"I'd say most of my patients, if they've already been vaccinated and we can reach them, they're often very willing to do what's right to protect themselves and get boosted," said Dr. Atul Nakhasi, a physician and policy advisor with the Los Angeles County Department of Health Services.

Only a handful of vaccinated patients are hesitant to get a booster, Nakhasi said, and through discussions, he's able to walk through their concerns — particularly if they're logistical, like taking off work.

If that effort is not made, Nakhasi warned that disparities that have already manifested will only continue to grow, erasing much of the progress that has been made to close the racial gaps on vaccine uptake.

Outreach is needed

In Los Angeles County, Black and Hispanic people account for 60% of the population, but only 30% of people who have gotten a booster -- a much smaller proportion.

"Disparities are again appearing within the data on who is getting the boosters," Nakhasi said.

And the omicron variant has made it clear that the outreach, especially among communities that already have a shortage of health care, will need to be a long-lasting effort, not a one-and-done.

"I think that goes to the core. We want that closure but unfortunately COVID is not giving it to us," he said. "So we need to make sure we build long lasting bonds to our communities, because it's become evident that there's a need for more than just the initial series."

Khan, the physician in Chicago, also said outreach has been effective. While more patients have reached out to doctors asking for a booster in light of surging omicron cases, far and away it's the doctors who are initiating the conversation.

"If we're prompting them, they're saying yeah I'll take it. But only now is that message starting to turn," Khan said.

"I'm just hoping we're not too late," he added.