Ashley Judd shines light on coping with mental health after death of mom Naomi Judd

As Ashley Judd copes with the loss of her mom, country music legend Naomi Judd, she is shining a spotlight on how to support loved ones with mental health struggles.

In an interview with ABC News' Diane Sawyer that aired Thursday, the actress confirmed Naomi Judd had died by suicide, and said she was sharing her story to help others who are struggling with mental illness.

"'I wish I could've, why didn't I,' the 'if only,' that is the bargaining stage of grief, and, for me, it is my least favorite stage of grief because it is such a mind game," Judd said in her first interview since her mother's death last month. "And that's another part of the lie, you know, that if I had done something differently, there would have been a different outcome."

In her grief, Judd said she kept going back to what she called the "three C's": "I didn't cause it, I can't control it, and I can't cure it."

"Don't compare your grief with others," she said of what she's learned so far. "Don't be too hard on yourself."

Judd also revealed to Sawyer that her mother -- part of the country music duo The Judds, which includes Ashley's sister, Wynonna -- died by suicide on April 30, just one day before her induction into the Country Music Hall of Fame.

"Our mother couldn't hang on until she was inducted into the Hall of Fame by her peers. I mean, that is the level of catastrophe of what was going on inside of her," Judd said. "Because the barrier between the regard in which they held her couldn't penetrate into her heart, and the lie that the disease told her was so convincing."

Naomi Judd, who was 76 when she died, was vocal about her mental health struggles during her life, writing about her journey in her 2016 book, "River of Time: My Descent into Depression and How I Emerged With Hope."

Ashley Judd told Sawyer that she wants to highlight the difference between a person who suffers from mental illness and the disease of mental illness itself, which affects as many as 50% of Americans at some point in their lives, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

"When we're talking about mental illness, it's very important to be clear and to make the distinction between our loved one and the disease," she said. "It's very real. It lies. It's savage."

For those who may be suffering from mental illness themselves, Judd encouraged them "to talk to someone, to share, to be open, to be vulnerable."

"There is a national suicide hotline," she said.

The National Alliance for Mental Illness (NAMI), a U.S.-based advocacy group, also has a hotline and a full online support guide with free resources to support both people living with mental illness and their loved ones.

The NAMI HelpLine, staffed by trained volunteers, can be reached Monday through Friday, 10 a.m. – 10 p.m., ET at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), info@nami.org or online chat.

While mental illness looks different for every person, common warning signs of mental health struggles include changes in sleeping habits and decreased energy levels, extreme changes in mood, excessive worrying, fear and sadness, changes in eating habits, and avoiding friends and social activities, according to NAMI.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741 for free, 24/7 support.

How to cope with the loss of a loved one by suicide

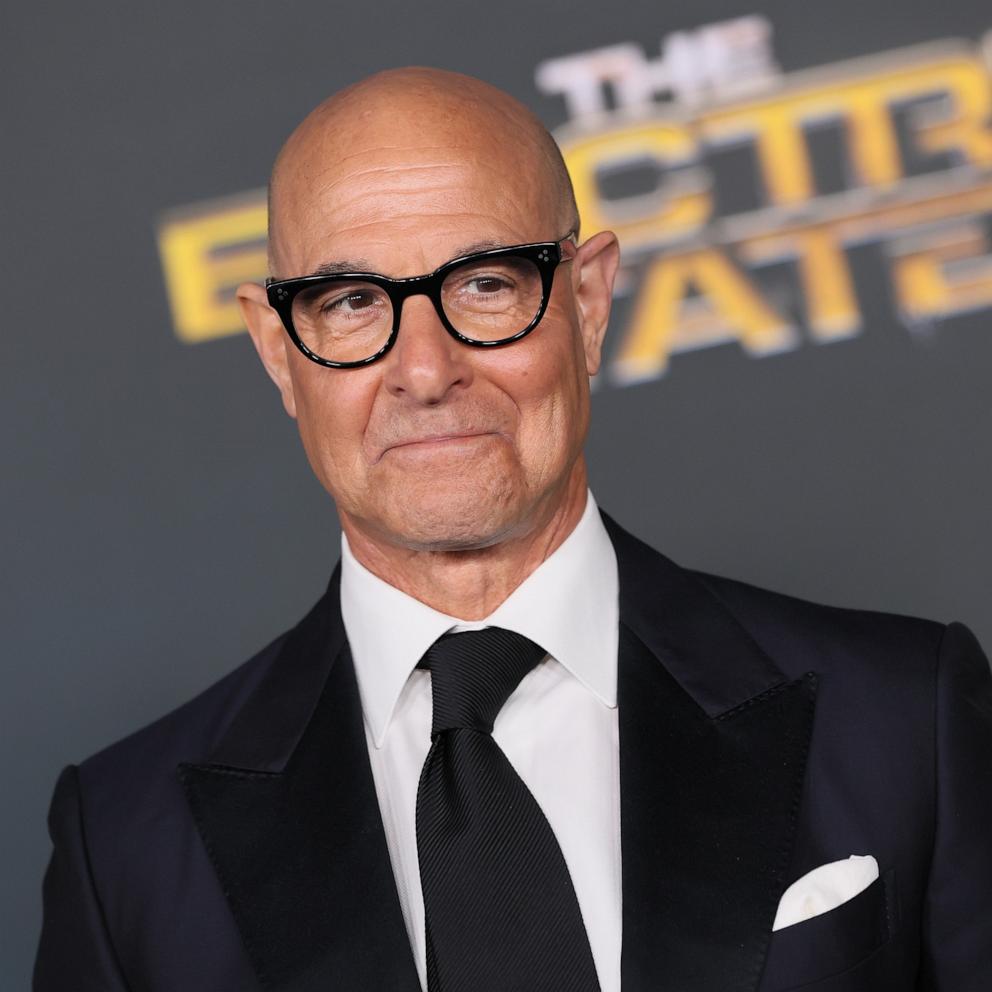

In 2019, Dr. Jennifer Ashton, ABC News' chief medical correspondent, released a bestselling book, "Life After Suicide," about her personal journey following her ex-husband Rob's death by suicide.

Ashton also worked with Everyday Health to create a companion guide to her book, “Surviving the Suicide of a Loved One,” which offers information for survivors of suicide and their support system.

Here are six tips from the guide's contributing writer, Katie Hurley, a licensed clinical social worker, and a child and adolescent psychotherapist in Los Angeles.

1. Know that it’s not your fault.

Many who have lost a loved one to suicide experience survivor's guilt, a feeling that they are to blame.

“We don’t ever get to know why someone took their own life and that’s really hard,” Hurley says. “Even if a note is left, it doesn’t really give us closure.”

Everyday occurrences may trigger thoughts of “What if I made that phone call?” or “What if I didn’t start that fight?” But as Everyday Health’s guide points out, it’s important to remember these thoughts likely don’t paint an accurate or complete picture of the situation.

One recommendation is to remind you that “I am not responsible for my loved one’s suicide” is to make a list of the ways in which you did support them and to keep it handy whenever “what ifs?” arise.

“We can relieve ourselves of some of that blame by looking at something that reminds us, ‘Here’s what I did to help them along the way,’” Hurley says, adding that writing out a list can be a therapeutic practice.

2. Know that the shock will lessen over time.

Shock is inevitable upon learning of the loss of a loved one by suicide, but for some, it can be crippling to daily routines and health.

“When we go into shock, we almost walk through the world like a skeleton of who we are,” Hurley says. “We might still be doing some daily tasks, but when the shock subsides, the dishes are piling up, the fridge is empty, you can’t remember to go to [the] store...that’s when the overwhelming begins.”

Everyday Health’s guide states that those who receive traumatic information may also find activities such as eating, showering and sleeping tough to accomplish or maintain with regularity.

Shock can also lead to the weakening of natural defenses, putting one at risk for illnesses.

It’s important to be cognizant of these factors, but shock will likely affect you less over time as you progress in your grief. Recognizing that frame of time will vary for each individual.

As such, it’s important to call your doctor should the feelings persist and continue to affect your everyday schedule.

3. Rely on your support system.

Coping with any type of loss can be a challenge, but a loss by suicide may be more complex given the stigma attached.

As a result, survivors may feel more alone in their grief.

A strategy for coping with tragedy could include seeking help from your support system.

Everyday Health’s guide suggests thinking about family and close friends who may be willing and able to help you out, and then expanding to others who have been supportive of you in the past, such as work colleagues, your faith-based community, the parents of your children’s friends, etc.

In the long or the short term, they may offer you a listening ear, or they may be helpful with day-to-day tasks you find challenging to accomplish after trauma.

Though some people may feel they’re being a burden on their support system, survivors can feel less alone and more on track with daily tasks by asking for and being willing to receive the help they need.

4. Seek counseling.

While learning to cope with the loss of a loved one, Hurley recommends seeking counseling. Looking for solace at your house of worship is also an option.

“A good first step for those who are resistant to therapy is to go somewhere where they feel at home,” Hurley says of seeking counseling at your church, mosque, synagogue or other holy place.

She also notes that survivors may find comfort seeking counsel from a familiar face and with principles of faith integrated into their therapy.

Additionally, while it may be difficult to open up to a complete stranger, Hurley says that seeking counseling from groups or specialists who focus on specific demographics or circumstances can also help a survivor cope.

5. Tackle the stigma.

The topic of suicide is one that can immediately make people uncomfortable. Unfortunately, much of the stress of destigmatizing it falls to the loved ones who have lost someone.

“It never ends,” Hurley says. “When I say I had someone very close to me die by suicide, people stare at me like I ruined the party.”

Hurley recommends being prepared for people’s discomfort, and making a script that they can practice saying in the mirror over and over again so the word suicide becomes more normal, and they feel able to share their story with others.

Additionally, Hurley says that if people don’t know how to respond, survivors have the right to turn away from those situations and recognize they’re not obligated to deal with an added layer of stress. In fact, she says, simply saying “I’m so sorry” to a survivor can show support.

“It’s not our job as survivors to end stigma and [I] don’t want survivors of the world to feel it’s their job to take on that cause,” Hurley says.

6. Show support.

There are many ways to show support to a survivor, from simply listening to offering help such as providing them a ride, returning calls or helping them schedule appointments, even if they don’t ask for it.

And, Hurley says, it can be helpful to allow survivors to talk openly about suicide.

“Acknowledge it, say, ‘I don’t know what to say but how can I help?’” she says.

A survivor’s support system should also pay attention to what a survivor is saying. Are they communicating feelings of hopelessness or unbearable emotional pain that go beyond the depression, isolation, confusion and anger that come from the initial shock? If so, they should be encouraged to get them help from a professional mental health practitioner to help cope with their grief following a suicide.

If you or someone you know is in crisis, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741. You can reach Trans Lifeline at 877-565-8860 (U.S.) or 877-330-6366 (Canada) and The Trevor Project at 866-488-7386.

ABC News' Joel Lyons contributed to this report.