In April, this educator lost her mother to COVID. Now NYC wants her to go back to work.

After her mother's death in April from COVID-19, Odalis Santana changed her voicemail message.

"Thank you all for the outpouring of love that you have given my family during this difficult time. I know that my mother would appreciate it," Santana's voice says on the tape. It's now August, but her fresh grief from the spring, captured on the recording, cuts through. "Thank you all for your texts, your messages, your emails. We really appreciate it. Our family really appreciates it."

Santana, 46, works as a universal literacy coach at an elementary school in the Bronx, where she supports teachers with young students who are struggling with reading.

She recalled her last days in the classroom in mid-March. Santana had asked her mother, Ana, to stay with her because of the pandemic. It wasn't an unusual request. Her mother often helped Santana, a single mother, with childcare, and Santana didn't want to leave her mother, who lived in public housing for seniors, alone. Besides, in addition to being mother and daughter, the pair were close friends -- "twins," Santana said.

On April 1, they got tested together for COVID-19. The tests came back positive. Santana's two children and her brother tested positive, as well. Santana was asymptomatic, but within days, Ana, who was struggling to breathe, was hospitalized. In the early hours of the morning of April 10, Santana received a phone call. Her mother's heart had stopped.

"The last time I saw her was when I sent her to the hospital by herself," said Santana, who used to talk to her mother on the phone multiple times each day. "I never got to say goodbye."

While Santana will never know whether she picked up the virus at school, she thinks back on the days when New York City restaurants and bars were shuttered, but teachers were still going into the classroom, regretfully.

"I’m just angry that we were told to go back to work without knowing what was happening," she said.

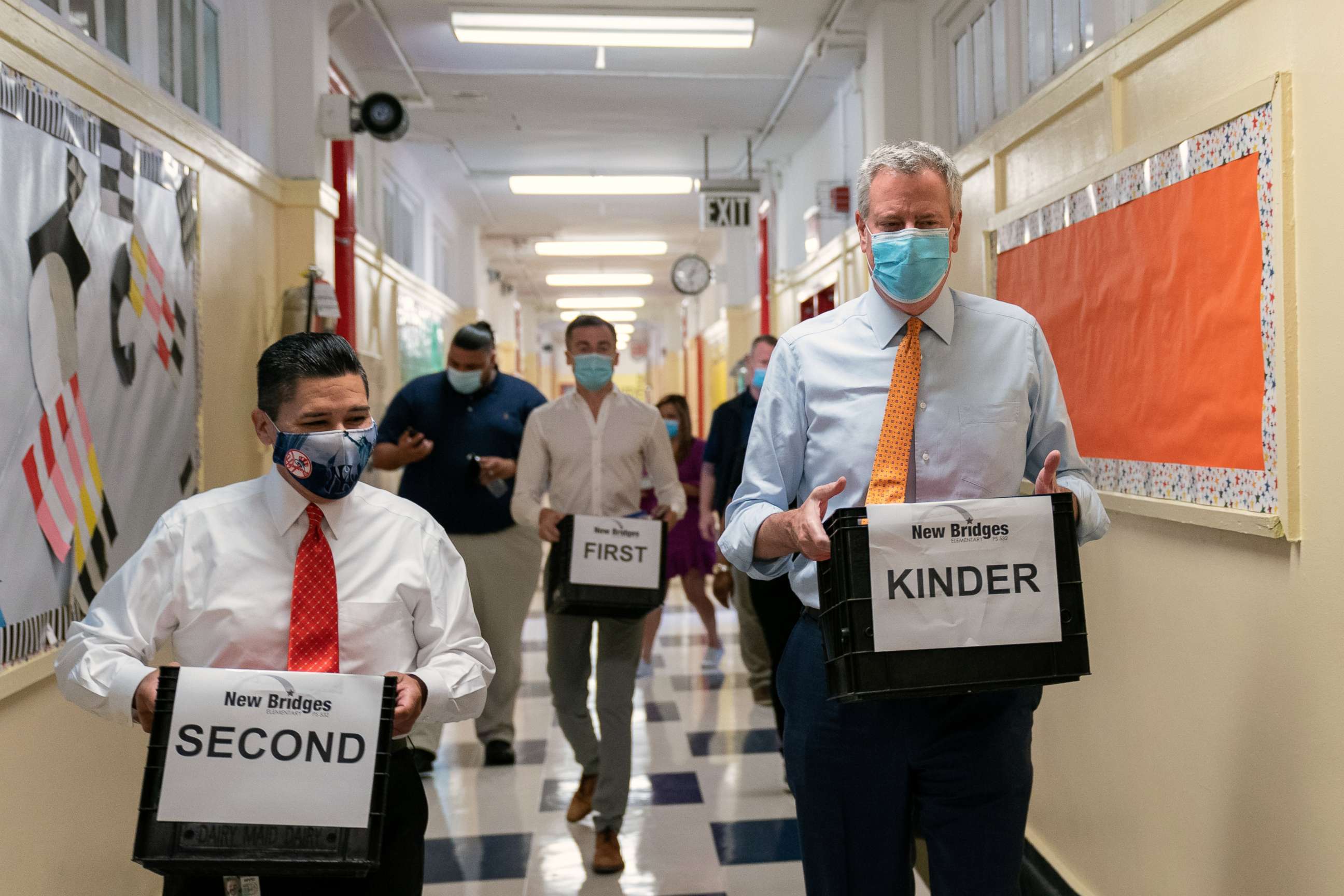

She doesn't blame the principal at her school, who she says, was "clueless, just like we were," about the pandemic back in March. But she's frustrated that Mayor Bill de Blasio and New York City Schools Chancellor Richard Carranza are pushing to reopen schools in person in September.

As the fall approaches, the issue of whether to reopen New York City schools, which were closed on March 16, to in-person learning has been hotly contested.

President Donald Trump and Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos and many other elected officials have repeatedly pushed schools across the country to reopen. And while nine of the country's 10 largest school districts have said that they will start the year remotely, New York City insists that it will make in-person learning an option come Sept. 10.

Reopening schools in-person would allow parents to go back to work and help ensure that vulnerable students in Black and Latino neighborhoods don't fall behind, the mayor has said.

New York's case positivity rate (the rate of positive cases to total tests) has been consistently below 1% in recent weeks, an indication that the virus is currently under control.

But those statistics belie the horror witnessed by educators and students last spring, particularly in black and Latino neighborhoods, when more than 20,000 residents died of the virus. New York City schools weren't spared the devastation. As of June, 79 department of education employees, 31 of them teachers, had died of COVID-19, according to the department.

In the meantime, educators have pushed back on the mayor's decision. Earlier this month, parents, teachers and students marched in lower Manhattan to protest the department of education's plan for reopening. On Aug. 12, the principals' union sent a letter to the mayor, urging de Blasio to "heed dire warnings" about his reopening plan and to delay in-person learning for 1.1 million public school students in New York City until later in September.

"We are now less than one month away from the first day of school and still without sufficient answers to many of the important safety and instructional questions we’ve raised on behalf of school leaders and those they serve," Mark Cannizzaro, president of the Council of School Supervisors and Administrators wrote in the letter.

"We know how overwhelming and uncertain this may still feel, and any student can opt into full-time remote learning and staff can request a medical accommodation if they need," Nathaniel Styer, a spokesperson for the Education Department, told ABC News in a statement.

"No matter what setting, the caring educators, counselors, and social workers across this city will continue to provide young people who are in crisis with support this fall."

If in-person schooling in New York City moves forward, Santana and her children won't be participating, she said. Santana let her kids' schools know they would be learning remotely this fall and put in a medical request to allow her to teach remotely, because she has asthma, an underlying condition that can trigger COVID-19 complications.

"As much as I love my job and my coworkers, I have to think about the safety of my family," she said.

Then there's the mental health toll that losing her mother and living in the Bronx, where a disproportionate number of people have died of COVID-19, has taken on Santana. In addition to her mom, friends' and coworkers' parents, as well as educators in neighboring districts, have all died of COVID-19, she explained.

"I went from being a social butterfly to a recluse," Santana said. "I’m scared. I'm suffering from PTSD. My children see a therapist every week. It's trauma all over the place."

Last month, Santana traveled to Puerto Rico, where her mother lived until she was 15 years old, to spread some of her ashes. Her mother loved the beach and singing salsa songs. During the holidays, Ana would cook traditional Puerto Rican dishes, like arroz con gandules, and gather her family around her.

Santana brought the remainder of her mother's ashes home in an urn, which she keeps in her room. Next week she plans to get a tattoo in her mother's memory, an elephant with two flamingos at its feet and butterflies flitting around them, all creatures her mother loved.

"I try to cope the best way I can, but it’s hard," Santana said. "I’m just hoping that the mayor and the chancellor come to their senses. I really don’t want my mother’s death to be in vain."

As of late August, with just weeks until the school year is supposed to begin, Santana is still waiting to hear whether her request to teach remotely will be approved.

What to know about the coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.