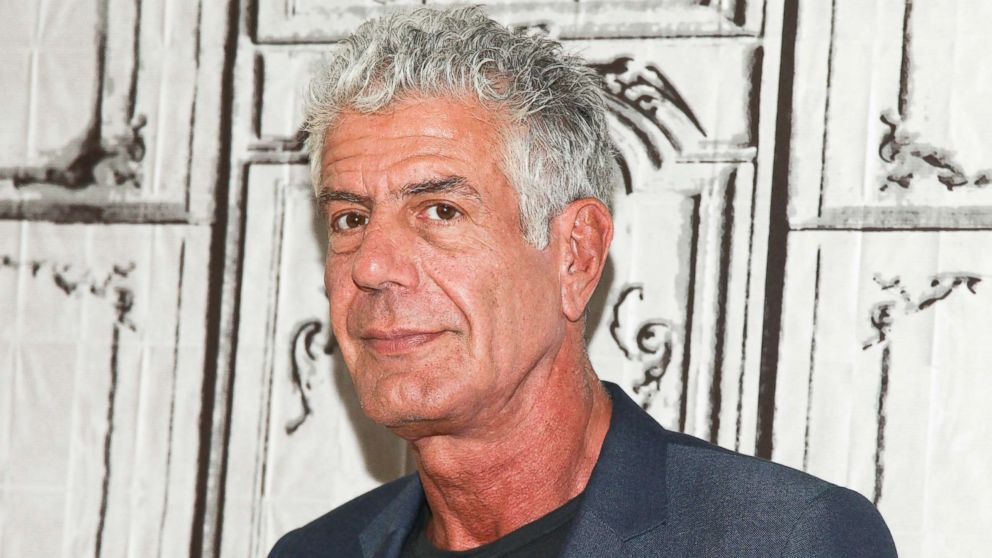

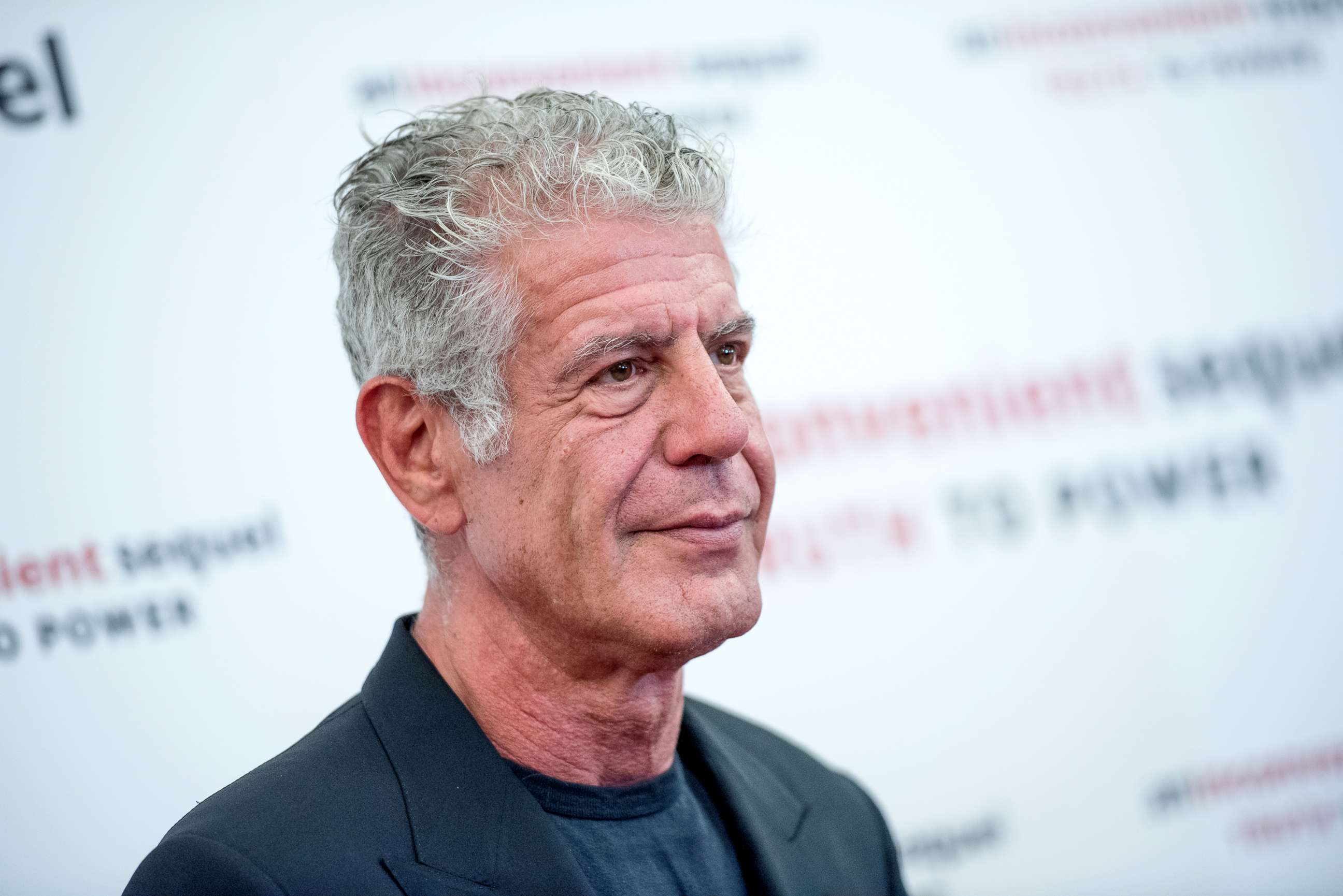

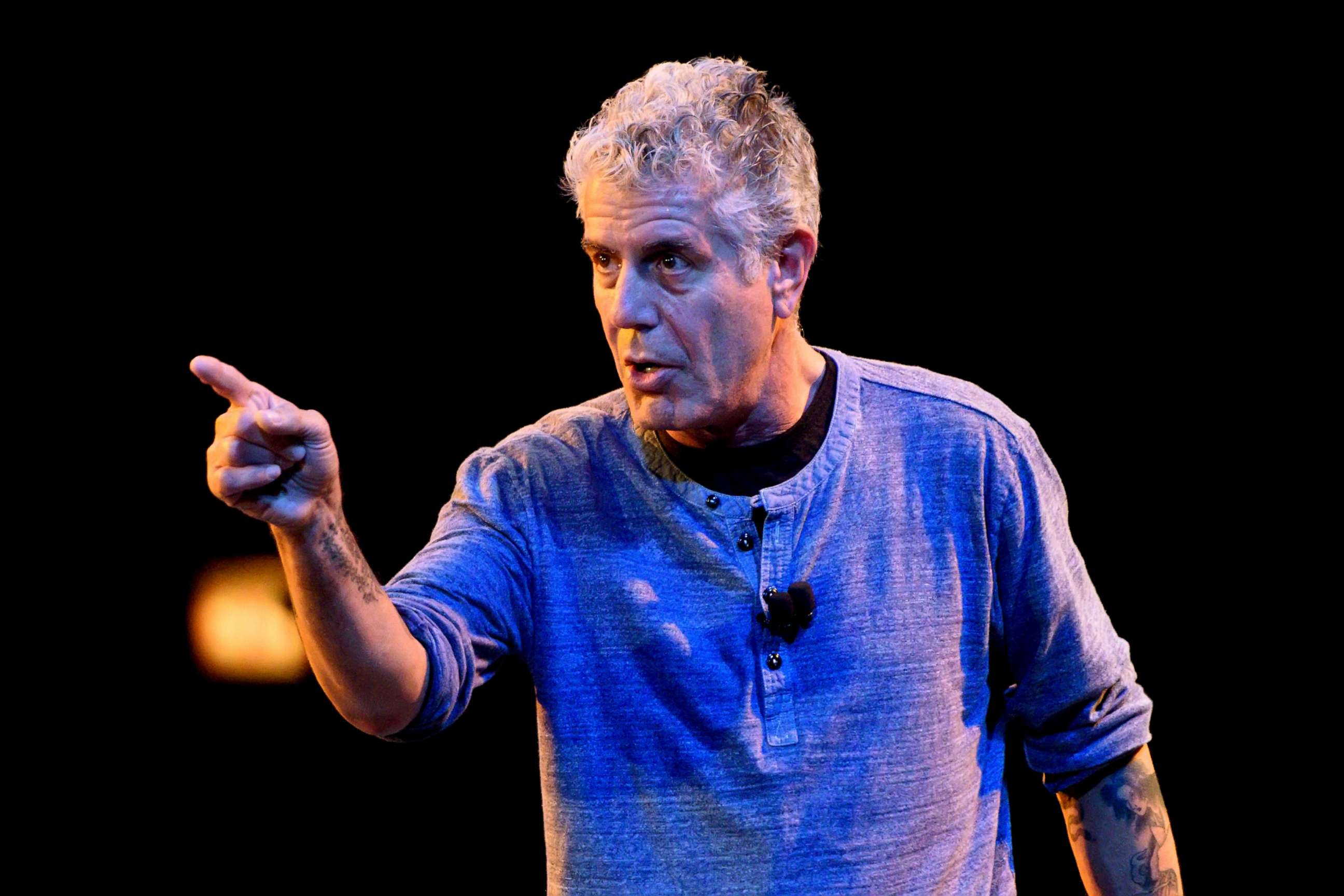

Anthony Bourdain dies in apparent suicide: What to know about the alarming rise in suicides and how you can help

The shocking death of chef Anthony Bourdain in an apparent suicide has once again placed a spotlight on what new data shows is a rising trend.

Suicide rates increased in nearly every state in the United States in 2016, with rates rising more than 30 percent in half of states, according to data released Thursday by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Bourdain, 61, was in France working on an upcoming episode of his CNN series, the network confirmed in a statement Friday.

The chef, who most recently was dating Italian actress Asia Argento, leaves behind a young daughter.

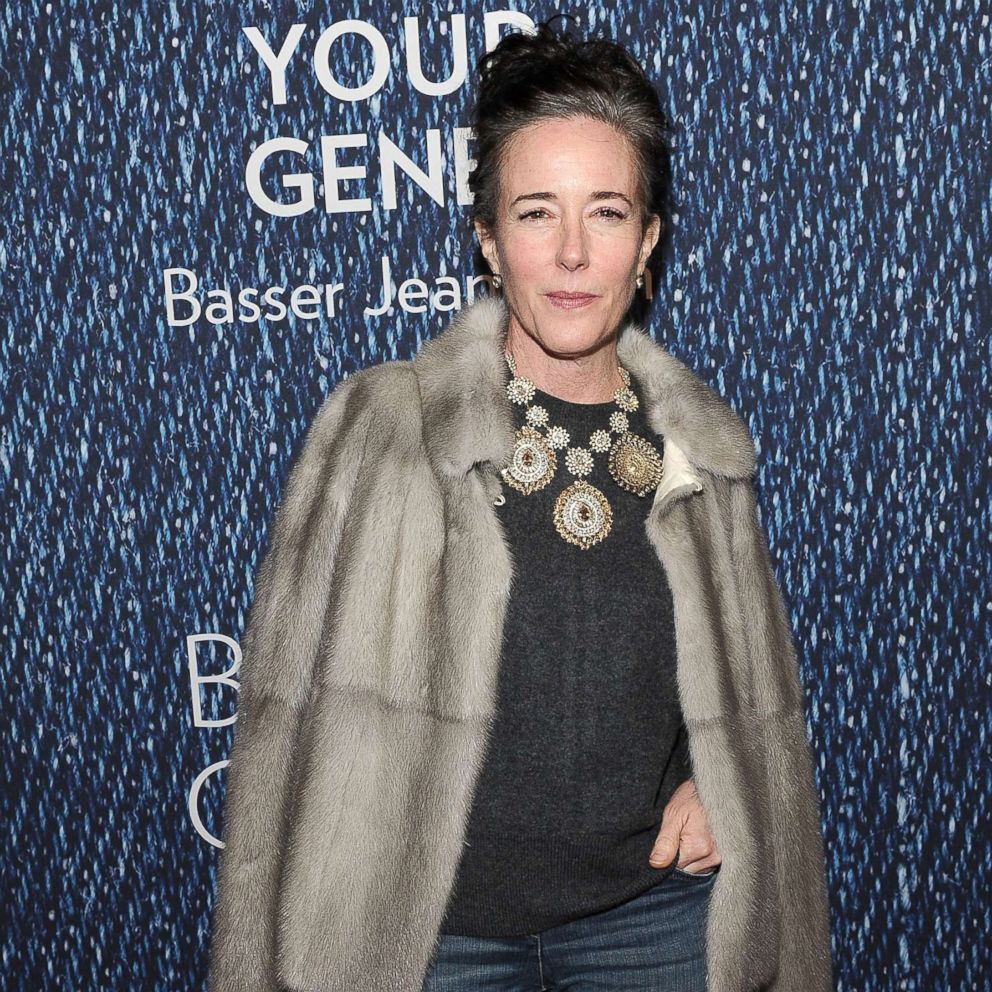

His death comes just days after fashion designer Kate Spade hanged herself in her New York City apartment.

Spade, 55, left behind her husband, Andy Spade, and their 13-year-old daughter. Andy Spade said in a statement to ABC News that his wife had been suffering from anxiety and depression for more than five years.

While Spade suffered from depression, a mental health condition is not always a predictor for suicide.

More than half of the Americans studied by the CDC who died by suicide did not have a mental health condition. Substance abuse, financial stress and relationship problems or loss are all factors that contribute to suicide risk, data shows.

Suicide remains the 10th leading cause of death in the U.S., according to the CDC.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, a 24/7, free and confidential resource, has seen a 25 percent increase in calls since Spade's death, a figure the lifeline's director called "highly significant."

"When people do call the lifeline, evidence clearly shows that suicidality is reduced and distress is reduced," Dr. John Draper, director of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, told "GMA." "The more we get the number out, the more we help save lives."

Where is help available?

Questioning suicide? Call someone, anyone: A friend, neighbor, family member, religious figure, hospital, doctor, mental health specialist, the police department or the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255).

It is important to remember you are not alone and people do want to help you, regardless of what you think.

Someone who calls the lifeline will reach a trained counselor, according to Draper.

"The counselor [will] listen to the person non-judgmentally and assess the nature and severity of their problem and, based on that assessment, can help get them care."

What should family and friends look for?

Significant changes in behavior are major warning signs that a person, especially one with depression, may be slipping into suicide, according to Dr. Dan Reidenberg, executive director of Suicide Awareness Voices of Education (SAVE).

If someone with depression is acting out of character, it is time to ask more questions, get others involved and take action, he explained.

Other changes in behavior that may be red flags are withdrawal from family, friends, work and social activities, a change in activity level, increased anxiety, which can be restlessness or agitation, and a lack of sleep.

"Look and listen for warning signs because it is not as if just one morning someone wakes up and says, 'Today is the day I’m going to do this,'" Reidenberg said. "It happens over time and falls on a continuum."

How can you help a suicidal person?

The most important thing loved ones can do is to be available, experts say.

Being available can mean being there to listen, without judgment, and to check-in continually to say something as simple as, "'Hi, how are you doing? I'm available and around,'" explained Reidenberg.

"Reassure them that they are important to you, you want them to be around and want them to be well," he said. "The reassurance that people care by statements and words mean a lot to someone who emotionally is drained from the depression."

Keeping a schedule of eating three times a day and waking and sleeping at the same time each day for structure can be important for people with depression, according to Reidenberg.

Finally, be willing to move past the stigma of speaking about depression and ask the person direct questions.

"If you care about someone, it’s really important to ask, ‘What are you doing about this? Are you talking to someone? Have you tried medication?'" Reidenberg said, adding that checking in on those three questions later is also important.

The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline offers five steps to help someone who may be considering suicide.

Step One: Ask. There is a common misconception that asking someone if they have/ are considering killing themselves puts the idea in their head — it does not. Do not be afraid to ask!

Step Two: Keep them safe. If someone admits to considering suicide, it is important to seek immediate medical attention, especially if they shared their plan with you or have access to firearms, the number one cause of suicide (50 percent).

Step Three: Be there. Listen without judgment and with empathy. Let them know they have a shoulder to lean on when they need.

Step Four: Help them connect. Help them find a support system to reach out to. Support is very important for someone battling the idea of suicide. Those who have attempted to harm themselves are often at risk of another attempt at suicide.

Step Five: Follow up. Following up could mean preventing thoughts of suicide or another attempt.

Seeking a professional who can help and monitor a suicidal person can also make a big difference. You can also call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255, whether you yourself are suicidal or you are worried about someone you know.

How common is suicide?

In 2016, 9.8 million people had serious thoughts of suicide, 2.8 million made a suicide plan and 1.1 million attempted suicide, according to the Suicide Prevention Resource Center.

This translates to one suicide death every 11.9 minutes, and one suicide attempt every 29 seconds.

A 2008 Harvard study found that the lifetime chance of suicidal thoughts for adults across 17 different countries was 9 percent.

The CDC recommends that the government, health care system, employers, schools and community organizations treat suicide as a public health issue.

Who is at risk for suicide?

Suicide affects all ages.

The CDC report found that suicide rates among women have risen more than overall suicide rate.

Nearly 9 percent of youth in grades nine through 12 reported that they had made at least one suicide attempt in the past 12 months, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, based on the 2015 Youth Risk Behaviors Survey.

Suicide is linked, but not limited to, mental disorders, particularly depression and alcohol use disorders.

The strongest risk factor for suicide is a previous attempt at suicide, according to the American Psychiatric Association.

Certain events and circumstances may increase risk such as having a psychiatric illness including, but not limited to, depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and anxiety disorders.

While depression is a contributory factor for most suicides, it does not need to be present for a suicide to be attempted or completed, according to the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention.

Other risk factors for suicide include chronic physical illnesses, family history of suicide, history of exposure to trauma or abuse, recent losses or life stressors, military service, hopelessness and impulsivity, misuse of alcohol and drugs and access to lethal means such as firearms, experts say.

Suicide risk also increases with age.

How is depression diagnosed?

Every time you see your primary care provider you are likely being assessed for depression.

When you enter the exam room, you may complete an assessment you don’t even know you are completing. The exam, the PHQ2, includes the following question: “Over the past two weeks, how often have you been bothered by the following problems: Little interest or pleasure in doing things? Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless?”

If someone screens positive on this, they are asked another seven questions (the PHQ-9) to determine whether they meet the criteria for depression.

Calls for change

Bourdain's and Spade's deaths have reignited the call for a national conversation about suicide and mental illness.

"Depression has been called the 'invisible disease' because there's not an X-ray we can do," said Dr. Gail Saltz, a psychiatrist. "There's not a blood test we can do and so it it is so prevalent and yet so under recognized."

Adam Grant, a high-profile psychologist based at the University of Pennsylvania, shared a reminder on Twitter that "depression is a medical condition" and should be discussed and treated accordingly.

A Facebook message that has been shared more than 230,000 times points out that the public knows more about celebrities' battles with breast cancer and heart disease than their struggles with mental illness.

"I knew when Patrick Swayze was battling pancreatic cancer. I know that Cynthia Nixon is a breast cancer survivor. I know that Selena Gomez has lupus and recently had a kidney transplant," Claudia Herrera wrote on Facebook in the wake of Spade's death. "I know that Dave Letterman suffers from heart disease. I know that Lance Armstrong is a testicular cancer survivor."

"But I didn’t know that Kate Spade suffered from depression. Or that Robin Williams did," she wrote. "Because somehow society has made it more acceptable to talk about breasts and testicles than about the mind and the chemicals and hormones it releases and controls and the messages it relays."

Draper, of the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline, says the stories of suicide attempt survivors must also be told to create a "contagion of hope."

"For every one person dies, we don’t read about the other 280 who think seriously about suicide but do not kill themselves," he said. "Those are the stories that we must pay attention to."

Draper explained, "It helps people be reminded that they can, and typically do, get through this, and here’s how."

ABC News' Medical Unit residents Eric Ascher, Sima Patel and Karine Tawagi contributed to this report.

If you are in crisis, please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or contact the Crisis Text Line by texting TALK to 741-741.