What Americans need to know about the government's VAERS database: ANALYSIS

Nearly 20 years ago, the federal government launched a massive crowdsourcing project: A database filled by doctors and patients that could give an early warning if problems arose with any of the millions of vaccines Americans take every year.

The system, called VAERS, the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, has now been credited with identifying an extremely rare chance of a blood clot after the Johnson & Johnson vaccine.

But with newfound attention on VAERS, this crucial public health system -- which anyone can access -- is ripe for abuse, misuse and plain misunderstanding.

Key figures in the anti-vaccine movement have latched onto the public database, incorrectly saying the vaccines directly caused numerous injuries listed in VAERS. Meanwhile, concerned citizens are increasingly stumbling upon the database and finding themselves alarmed by the reports.

Although VAERS contains millions of reports of injuries following vaccinations, the vast majority of those injuries are coincidental. The system accepts any report of an adverse event following vaccination, even if it's not clear the vaccine caused the problem.

For example, in the United States, someone has a heart attack every 40 seconds. Some may have received a COVID-19 vaccine shortly prior to their heart attack and that report may have been filed to VAERS. But it does not mean the vaccine caused the problem.

"VAERS has been in place almost 20 years. It has been used as a radar system to detect signals on vaccine safety issues ... and has been ramped up in response to the COVID vaccine," said Dr. William Schaffner, a professor of preventative medicine and infectious diseases at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

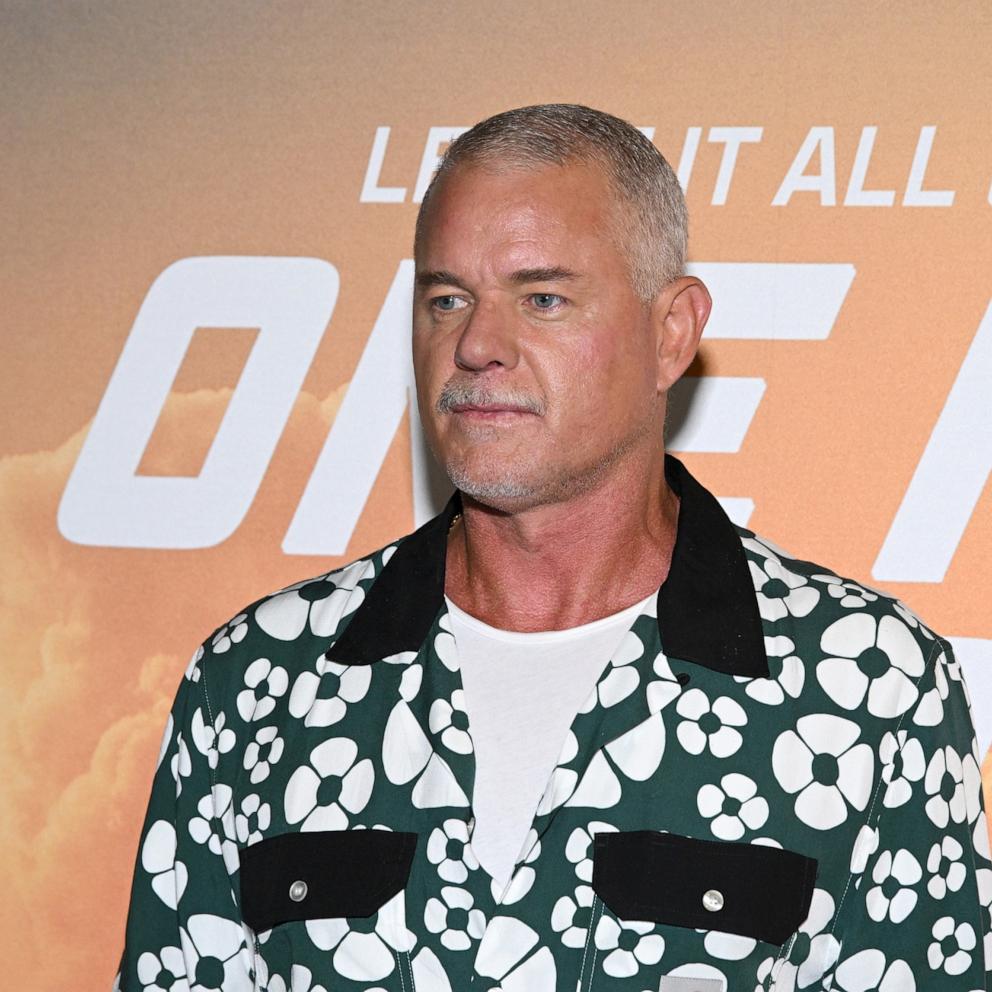

Added Dr. John Brownstein, an epidemiologist at Boston Children's Hospital and an ABC News contributor: "This is a frontline system which can quickly capture data about what's happening in the population through self-report."

Anyone can use VAERS. All you need to do is download the app V-safe or enter "vaccine reporting" in Google. It is very user-friendly and anyone can access the data reported on VAERS.

"This is truly a model of transparency," Schaffner said.

While abuse and misunderstanding are possible, a fully transparent system builds confidence that the pharmaceutical industry and government can't hide cases of adverse events during mass immunization campaigns.

And because it's a crowdsourced system, VAERS is the best way to detect extremely rare side effects that may not otherwise have been identified.

"Think of how useful it has been. VAERS found a needle in a haystack," Schaffner said. "These clotting events with [low platelets] occurred at a rate of 1 in over 1 million doses of vaccine. It found a signal, which was investigated, and health officials immediately convened an emergency meeting."

Federal and pharmaceutical authorities are alerted when the frequency of a side effect is higher than would be expected in a large unvaccinated population, explained Dr. Nabarun Dasgupta, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina.

For public health experts, the expected frequency of health problems -- such as one heart attack every 40 seconds -- is called the expected "background rate." The VAERS system helps identify problems that exceed the expected background rate.

One, however, must be cautious of misinformation entered on the site, including false reports.

Government agencies look systemically for patterns related to the vaccine, and when someone gets sick or dies shortly after the vaccine, this is investigated in a very serious fashion to ensure there is no link or inaccurate reporting.

"It's funny because when you click submit, there is actually a big warning sign ... if misinformation is entered, it can actually result in legal action," said Brownstein. "There is sort of a history for those who may want to perpetuate misinformation about vaccines to use fear as a tool to do so."

Despite its limitations, VAERS has proven to be a valuable tool. Patients receiving the vaccine are strongly encouraged to use the system so future adverse events can be identified.

Karine Tawagi, M.D., is a hematology and oncology fellow at Ochsner Medical Center in New Orleans and a contributor to the ABC News Medical Unit.