ADHD rates in kids have increased over the past 20 years, new study says

Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder, or ADHD, has become more common in children over the past twenty years, according to a new study.

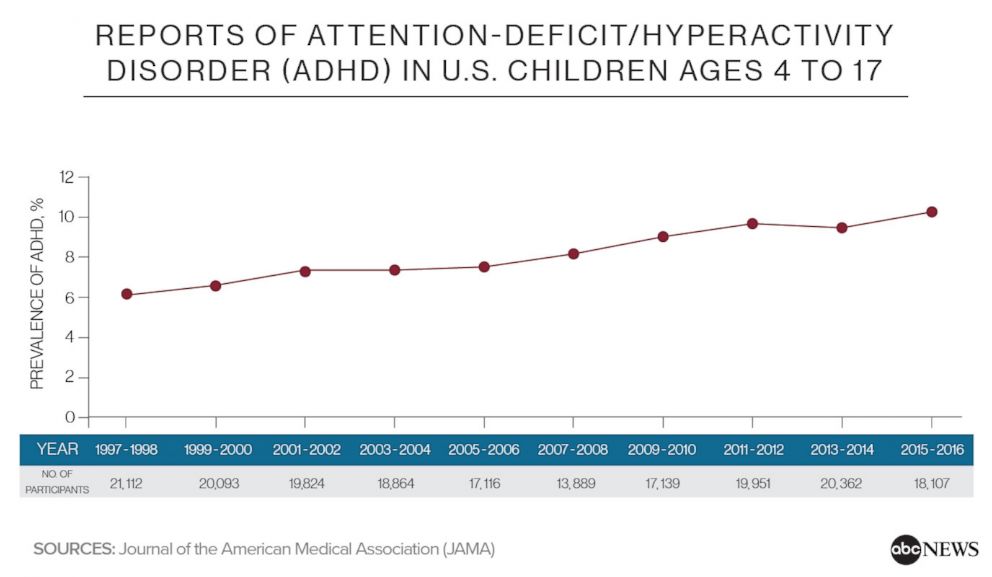

The prevalence of ADHD in U.S. children and adolescents has increased from 6.1 percent in 1997 to 10.2 percent in 2016, the study published Friday in the Journal of the American Medical Association, or JAMA, said. The way the disorder is evaluated likely plays a part.

"The diagnosis and assessment for ADHD has evolved over the past few decades. The diagnostic criteria that we use is now a little more liberal and captures cases that the older criteria would have left out," said Dr. Neha Chaudhary, a child psychiatrist at the Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School and co-founder of Stanford Brainstorm, in an interview with ABC news.

The newest criteria allow for the diagnosis to be made if a child has symptoms of either inattention or hyperactivity that interfere with his or her quality of life — as opposed to previous criteria which required the symptoms to be present in multiple environments.

"This is especially important in young girls who often fly under the radar as they don't always have the same, obvious symptoms of hyperactivity as do their male peers," Chaudhary, who was not involved in the study, said.

In the 20-year study, boys were diagnosed with ADHD at higher rates, an average of 14 percent, compared to girls at 6.3 percent. There were also racial differences in the prevalence of the disorder: African American children had the highest prevalence at 12.8 percent, followed by white children at 12 percent and Hispanic children at 6.1 percent.

The team calculated the rates by using yearly surveys contained within the National Health Interview Survey, a large nationwide study conducted by a branch of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC. Researchers followed 186,000 children ages 4 to 17 every year from 1997 to 2016.

The reasons for the increase in ADHD rates were not directly studied. But the researchers suggested that efforts to train physicians in the disorder, improved awareness in the public, improved access to mental health services and changes in the diagnostic criteria may have all led to an increased number of children being diagnosed with ADHD.

The symptoms of ADHD include inattention, as well as hyperactive and impulsive behavior, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM 5, which psychologists and psychiatrists generally follow.

An ADHD diagnosis is often made based on a child or teen having a number of inattentive and/or hyperactive symptoms for at least six months in social, academic or occupational environments.

Recent evidence also suggests that frequent use of digital media may be linked to an increase in symptoms that are typically associated with ADHD. But long-term study has not yet been possible.

"I think it's too early to tell what the link is between digital media use and ADHD," Chaudhary said.

"We live in a new age full of many more distractions," she added. "Even a healthy brain might be able to develop habits of overusing technology or becoming easily distractible. Some of it might end up looking like the criteria for ADHD without really being the same disease process in the brain."

The American Academy of Pediatrics noted some of the benefits of digital and social media use, including early learning, exposure to new ideas and knowledge and opportunities for social contact and support. However, the AAP also warned that the risks can include negative effects on sleep, attention and learning and higher incidence of obesity and depression, among others. The group recommends creating a Family Media Use Plan.

Dr. Edith Bracho-Sanchez is a pediatrician and a consultant for ABC news.