Period-tracking apps may help prosecute users, advocates fear

The Supreme Court's decision to overturn Roe v. Wade, leaving it up to individual states to decide whether to allow abortion procedures, has prompted abortion-rights advocates to urge women using period-trackers, and other digital apps that track reproductive health, to delete them.

“If you are using an online period tracker or tracking your cycles through your phone, get off it and delete your data. Now,” tweeted lawyer Elizabeth McLaughlin, founder of the female empowerment non-profit Gaia Project for Women's Leadership.

McLaughlin’s message, which was posted on the day Politico reported the leak of the Supreme Court’s draft opinion on Roe v. Wade in early May, has since been retweeted more than 59,000 times. The Supreme Court handed down its official decision on Roe v. Wade on June 24.

Abortion-rights advocates are ringing alarm bells not just about the use of menstruation-tracking apps, but the potentially incriminating digital trail of geo-location data, online transactions and web-search histories.

“It's not just that we're going back to a time before Roe v. Wade,” Leah Fowler, professor of health law and policy at the University of Houston, told ABC News’ “Start Here” podcast. "We're doing it with the surveillance apparatus in place that we couldn't have imagined even then,” she said.

Fears about criminal prosecution have grown among abortion-rights advocates as states with abortion bans institute penalties, which include possible fines and imprisonment, for abortion providers. For example, Arkansas has made performing or attempting to perform an abortion a felony punishable by up to 10 years in prison and a fine of up to $100,000. The only exception is if the mother's life is in danger.

Kentucky and Louisiana have had courts issue temporary blocks on their bans, which had stated anybody who performs or attempts to perform an abortion will be charged and face prison terms and/or fines.

According to Fowler, no matter their privacy policy, companies could still be forced to hand over consumers' data during the course of a criminal investigation.

And the data could also be at risk in civil litigation, Fowler said, through “discovery requests or other civil investigative demands,” that are not necessarily part of a criminal investigation.

“You don't only have to be in a place that has made [abortion] a crime or considers it homicide to be subject to potential legally valid requests for information,” said Fowler.

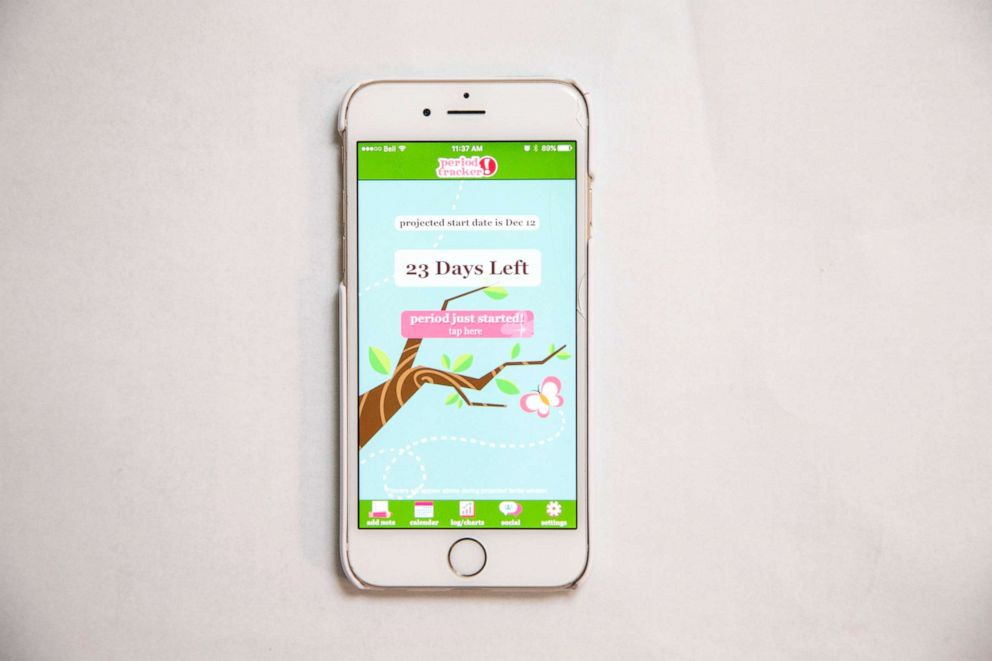

These period-tracking apps have millions of users every month who utilize the technology to better understand and help control their reproductive health. The apps can tell you when to expect your next period, if you might be pregnant and how far along you are, when you are the most fertile for conceiving and what sorts of symptoms you usually experience.

In June, politicians released a statement asking President Joe Biden to “clarif[y] protections for sensitive health and location data” as part of a larger call to protect abortion rights.

This week, Axios reported that Biden plans to ask the Federal Trade Commission to protect consumers’ data privacy specifically in the context of Roe v. Wade being overturned.

Last year, the period-tracking app Flo settled a complaint with the FTC which alleged that the company was selling users’ health data to Facebook and Google, as well as marketing and analytics firms, allegedly in violation of their own privacy policy.

As part of the settlement, the app agreed to an “independent review of its privacy practices” and committed to “get app users’ consent before sharing their health information.”

In the settlement, Flo "neither admit[ted] nor denie[d] any of the allegations."

On the day that Roe v. Wade was overturned, the company tweeted that it would soon be launching “Anonymous Mode,” which “removes your personal identity from your Flo account, so no one can identify you.”

A number of other period-tracking companies reacted to the decision.

The astrology-focused period-tracker app Stardust sent out a tweet two days after the Supreme Court decision that “we absolutely want to protect our users from bad actors, hackers and even our own government overreaching into our privacy.”

The company announced it had implemented an “encrypted wall” to protect users' data and that it was “working on an option for users to completely opt out of providing any personal identifiable information.”

The app Clue, which is based in Europe and beholden to more stringent privacy laws, said in a statement that “no data point can be traced back to any individual person.”

In response to the question of how companies’ privacy policies could protect consumers’ data in the face of a warrant, Fowler said, “you can’t turn over what you don’t have.”

“There are limits on the types of things that law enforcement can do when they're trying to get information from a company,” said Fowler. “That can inform how people might want to select period trackers.”