How one young activist is standing up for her Navajo community's COVID-19 relief

Shandiin Herrera was sheltering-in-place at her home in the Navajo Nation in March as the coronavirus swept through the country, when she got a call from her mentor, asking for help.

Her mentor, former Navajo Nation Attorney General Ethel Branch, asked the 23-year-old activist to join her in a COVID-19 relief effort for Navajo citizens so that they could safely quarantine at home during the pandemic.

Herrera, who lives in Monument Valley, Utah, a small rural community of less than 1,000 people, jumped at the chance to pitch in. She said outreach programming from the Navajo Nation government can miss smaller populations of Navajo citizens, like those in Monument Valley, and she wanted to help bridge those gaps.

“The reason why I immediately stepped out to be a part of the COVID relief effort [was] because I knew that if I didn't do it, my community would not be included,” said Herrera.

Herrera joined her mentor in working for the Navajo and Hopi Families COVID-19 Relief Fund. The effort was first launched as a crowdfunding campaign to raise money for two weeks of food and supply care packages so that Navajo citizens could safely quarantine.

By the end of its first day in March, the fund had raised $5,000.

Over the ensuing months, Herrera helped Branch with community work, like food supply distribution.

“I definitely have learned so much about community work and organizing, and especially working with different, really diverse groups of people,” said Herrera.

The organization provides relief to roughly 30,000 households by delivering food, potable water, cleaning supplies and personal protective equipment. Since March, the organization has raised nearly $5 million, according to its website.

Hererra says that the pandemic has brought national attention to the many of the longstanding systemic issues her community has faced over the years.

“A huge issue is figuring out how we can continue to elevate information … but also knowing what we need to do more of and making sure we’re reaching [all] families,” said Herrera. “Half of our community is still dirt roads... We don't have addresses. So even if we know someone is in need, we have no idea how to get to them.”

She said part of her work at the relief fund has been to help bridge the digital and information divide by implementing a Google+ program that helps to locate residents who don’t have addresses and therefore can’t be found on a map. To do this, she has been using the technology companies' "Plus Codes," which indicate a person's latitude and longitude on Google Maps in lieu of an address.

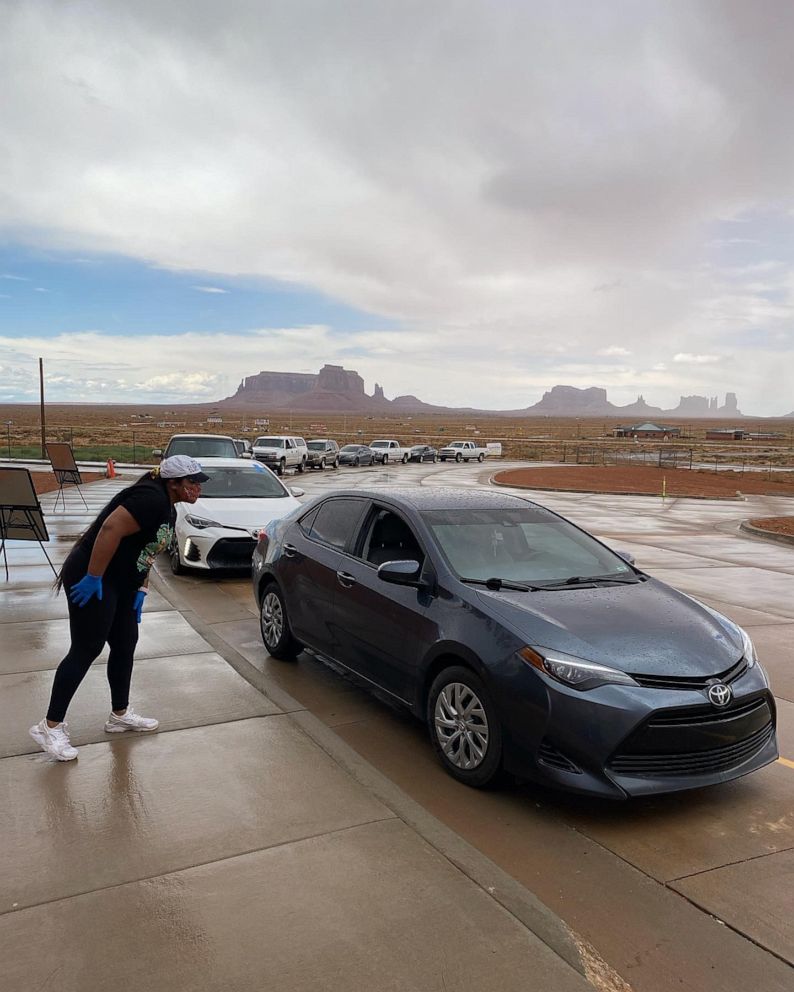

Herrera said they recently hosted a free drive-thru Google+ registration event.

“We had about 70 vehicles who came out, and in addition to that, we had contacted a local vendor and she was able to provide free lunch... So that was another thing I was able to do without funding,” said Herrera.

The fund has turned into a nonprofit organization called Yee Ha’ólníi Doo, which means “may the people have fortitude” in the Navajo language of Diné. She says the organization is led entirely by Navajo women.

“I've learned the family aspect of the work we're doing from all these amazing Navajo women, who come from very different professional backgrounds,” said Herrera. “[They’re] all able to weave together our experiences and our expertise to create such a well-functioning program and so I got to look up to all of them.”

Herrera graduated from Duke University in North Carolina in 2019 with a bachelor’s degree in public policy.

She said the decision to continue her education past high school was not an easy one. Many young Native people don’t see the benefit in going to college or, if they go, they find better opportunities outside of the Navajo reservation, she said.

“There are not a lot of young people in my community because most people who do go to college don't come back,” said Herrera. “For a lot of young Native people, we experience a lot of the same things and so I think that by sharing my experience ... it helps others feel seen as well, and helps motivate and encourage them [to make a difference].”

She chose to leave North Carolina because she obtained a Hometown Fellowship with the public service program Lead for America, which was established to incentivize young people to do community-centered work in their hometown.

Herrera went on to work for her reservation’s local government, which is called a Chapter House.

“One of the things I take a lot of pride in is not forgetting where I come from and figuring out a way to come back and give back to my community,” said Herrera.

Upon starting the new job, she quickly realized the overwhelming amount of work that needed to get done. The issues at hand range from a lack of broadband access and potable water to food insecurity. The office closed when the pandemic hit, but her experience there gave her the skills she needed to make a difference with the COVID-19 relief fund.

“There are only 13 grocery stores in the entire Navajo Nation -- that is the size of West Virginia,” she said.

A 2014 study published in the journal Public Health Nutrition found that of 276 members of the Navajo Nation selected randomly at food stores and other community locations, 76.7% had some level of food insecurity.

“Reducing food insecurity on the Navajo Nation will require increasing the availability of affordable healthy foods, addressing poverty and unemployment, and providing nutrition programmes to increase demand,” the study said.

Native Americans are governed by multiple legal structures, including tribal laws that each tribe may create and enforce. The Navajo Nation is the largest community of Native Americans within the United States, with its own bureaucratic administration that organizes everything from tourism on the reservation to social services for Navajo citizens.

Herrera said she hopes to become a lawyer one day and study Federal Indian Law.

Currently, only 0.2% of all lawyers are Native, according to American Bar Association.

“[Law school] is super expensive and I didn’t know anyone who went to law school,” said Herrera, who applied to seven schools, mainly on the West Coast.

As she continues her education, Herrera said she wants to be a Westernized resource for Navajo people while also maintaining her identity as a Navajo woman.

“I'm going to be educated and have a degree and create a name for myself in this Western society,” said Herrera. “But also, I need to maintain my own identity and culture and continue to be an active member of my tribal community.”