Where are all the women in kids' history books?

March is Women's History Month, which means for the past few weeks, education-focused websites have been full of lessons plans and ideas for teaching children about women in history.

What happens in kids' history books the other 11 months of the year, when women are not a focus, is another story, data shows.

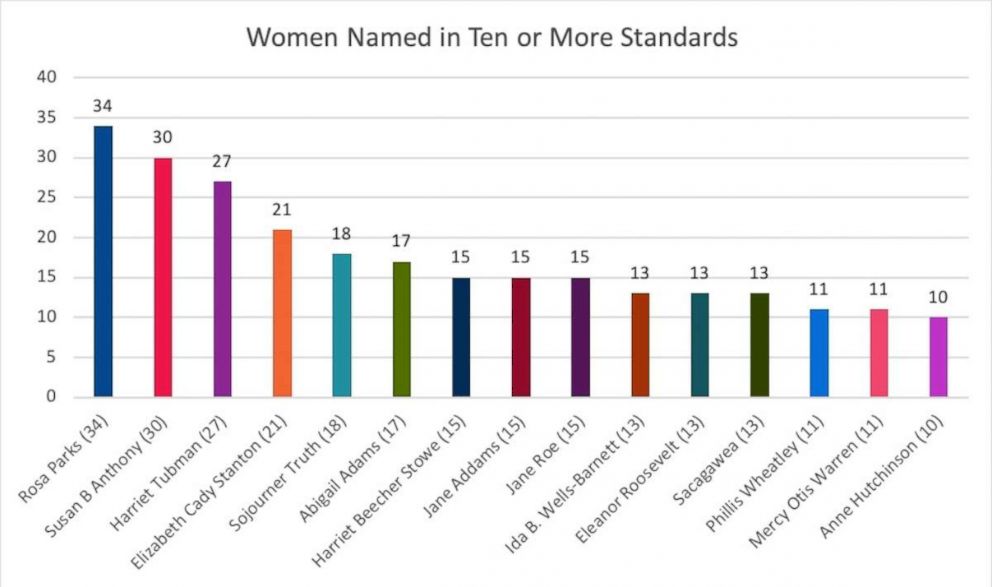

Approximately one woman for every three men is mentioned in states' social studies or history standards in place as of 2017, according to an analysis by Smithsonian magazine.

Keep in mind that Women's History Month, declared each March by a presidential proclamation, began as an effort by five women, most of them teachers, to "broadcast women’s historical achievements."

The leader of the five women, Molly MacGregor, was a 24-year-old high school history teacher in Santa Rosa, California, in 1972 when she couldn't find an answer in textbooks to answer a student's question about the women's movement.

"We were trying to tell the stories that at that point very few people knew or remembered," MacGregor told the Los Angeles Times about the effort she and her colleagues undertook to "write women back into history.”

How woman are portrayed -- and not portrayed -- in history books

Smithsonian magazine's analysis of women in history built on a 2017 report by the National Women's History Museum (NWHM) that looked at school social studies standards for each state and Washington, D.C.

The report's authors entered every standard that referred to a woman or a topic associated with women into a database. The researchers looked at the state standards, made by each state's education department, because the U.S. does not have shared social studies or history standards, according to the museum.

(MORE: 4 female entrepreneurs describe how they learned to embrace their ambition)

The purpose of the report was not to look at how women's history was covered, but at how women are included in the history being taught to kids.

In one example, women's topics are often included as an "addendum to the main storyline" and addressed as a group, the report found.

"This method overlooks that all groups, whether the powerful elite or those marginalized by economics, race, or culture, also include women," the authors wrote. "Factors other than gender often are more important to an individual woman's perspective or basis for her actions. Women have never acted as a unified group."

In another example, the curriculum standards use a timeline of wars and economic and political decisions that were mostly made by men because women were sidelined due to laws and the culture at the time.

"As long as history curriculum follows the traditional timeline, the study of women's experiences is subject to marginalization," the authors concluded.

Sarah Drake Brown, Ph.D., chair of the board of directors for the National Council for History Education, who was not involved in the report, echoes the belief that women's history has "never meant only one thing" in any historical period in the U.S. or the world.

"We have to help students think about how race, ethnicity, religion, and class might intersect in the lives of women at different points in time and in different places," said Drake Brown, also an associate professor of history at Ball State University. "It’s not about 'fitting women in' traditional narratives; it’s about expanding students’ understandings to help them think about the diverse experiences and various perspectives of women."

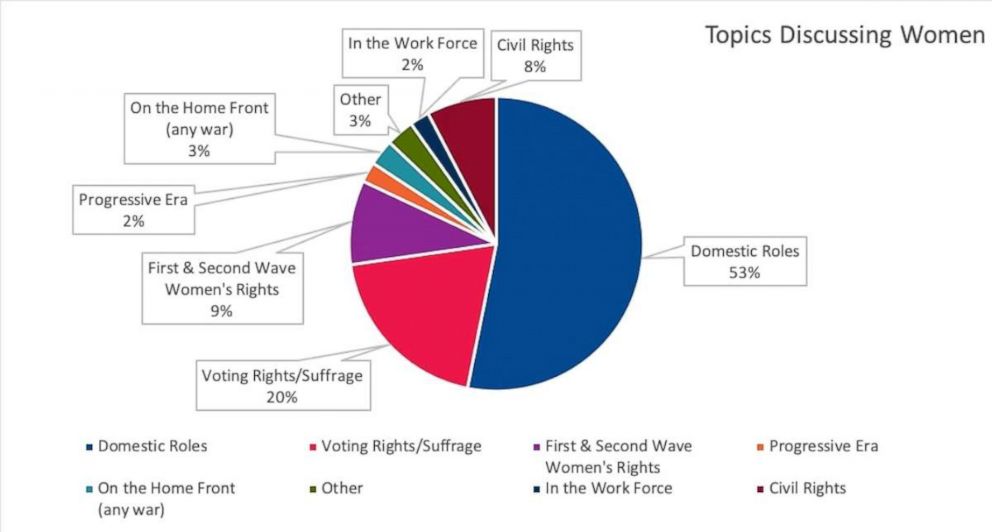

The NWHM's report found women's domestic roles are often "overemphasized" in history standards.

Women's history is studied the most at the elementary school level because that is when students are learning about "daily life and family life" in history, according to the report. Fifty-three percent of women’s history mentions fall within the context of family and domestic roles.

In contrast, women’s suffrage and women's rights account for 20 percent of the mentions.

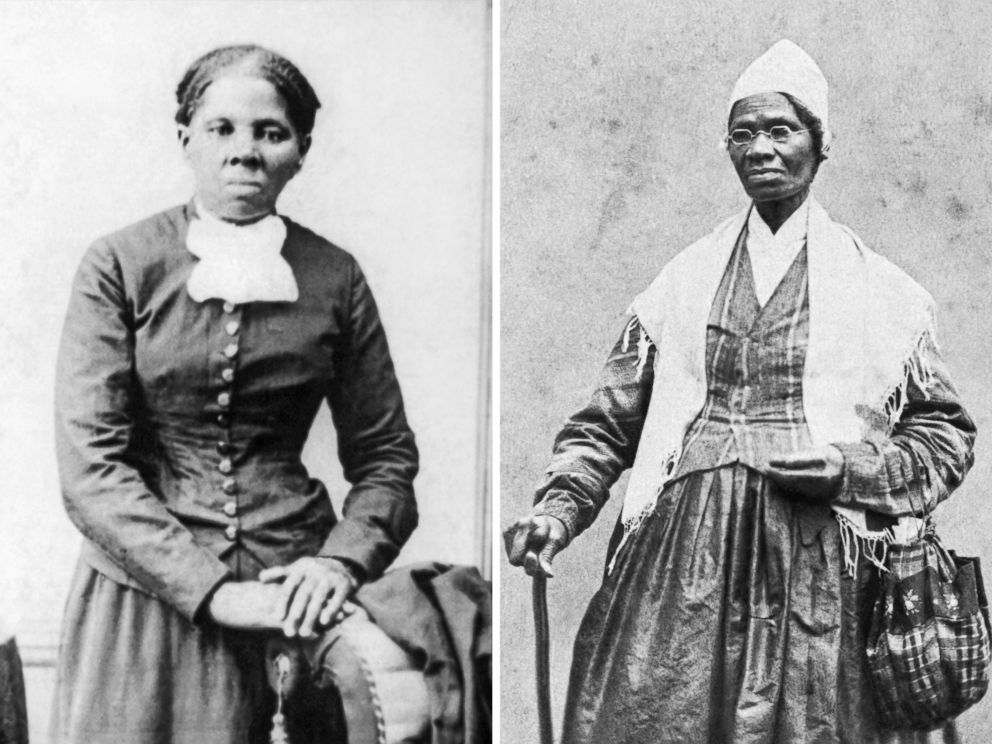

“When I was growing up, women were not that well represented, so I didn’t really know all my potential. I just didn’t see it," Sasha Bonner, who dressed her daughter up as powerful African-American women, told "GMA" in February. "I grew up thinking Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth were the same person because I learned about them at the same time on the same day during Black History Month."

Filling in the gaps of 'herstory'

When school standards don't call for women to be fully accounted for in history, it is left to teachers to make the effort and other organizations, like the National Women’s History Museum, to offer the resources.

"Educators want to be filling out the details when they’re teaching, not just peppering in recognizable names," said Colin Sharkey, executive director of the Association of American Educators, which bills itself as the largest national, non-union, professional educators' organization. "They want to actually help a student feel how women would have felt in that society."

"There’s a sense that how we teach history is incomplete, and women's history is a major example of what’s still lacking," he said.

The National Women's History Museum launched its 2017 study on social studies standards because it wanted to improve the "relevancy and usefulness" of the resources on women in history that it provides online to teachers and students.

Scholastic, which says it sells approximately one out of every two children’s books purchased in the U.S., also offers resources on its website that, again, teachers have to go to outside of their classroom time to utilize.

"It is always on the minds of our Scholastic Magazine editors to infuse diverse voices across all of our fiction and nonfiction content," Lauren Tarshis, senior vice president and editor-in-chief/publisher of Scholastic Magazines, told "GMA." "Throughout the entire publishing year our titles showcase inspiring women and girls to ensure our young readers see the powerful role women play both historically and in present day."

More advanced technology is also popping up to help women be remembered in the history books. An augmented reality app, "Lessons in Herstory," that debuted this year at South by Southwest unlocks a story of an important female historical figure when it is scanned over an image of a male historical figure in a popular textbook, "A History of US, Book 5: Liberty for All? 1820–1860."

Drake Brown of the National Council for History Education said the council and other organizations like it, along with public history sites, work together to "support teachers as they use materials that are more inclusive and that help broaden students’ understanding of what women’s history is."

What takes so long to fill out women's story?

Even with the online resources available, it is still left up to each teacher's desire, willingness and availability -- on top of their pre-existing workload -- to sort through it all and make an accurate portrayal of women in history part of their curriculum.

Textbook companies can take years, or, in the case of women in history, decades to redo what is taught in history books.

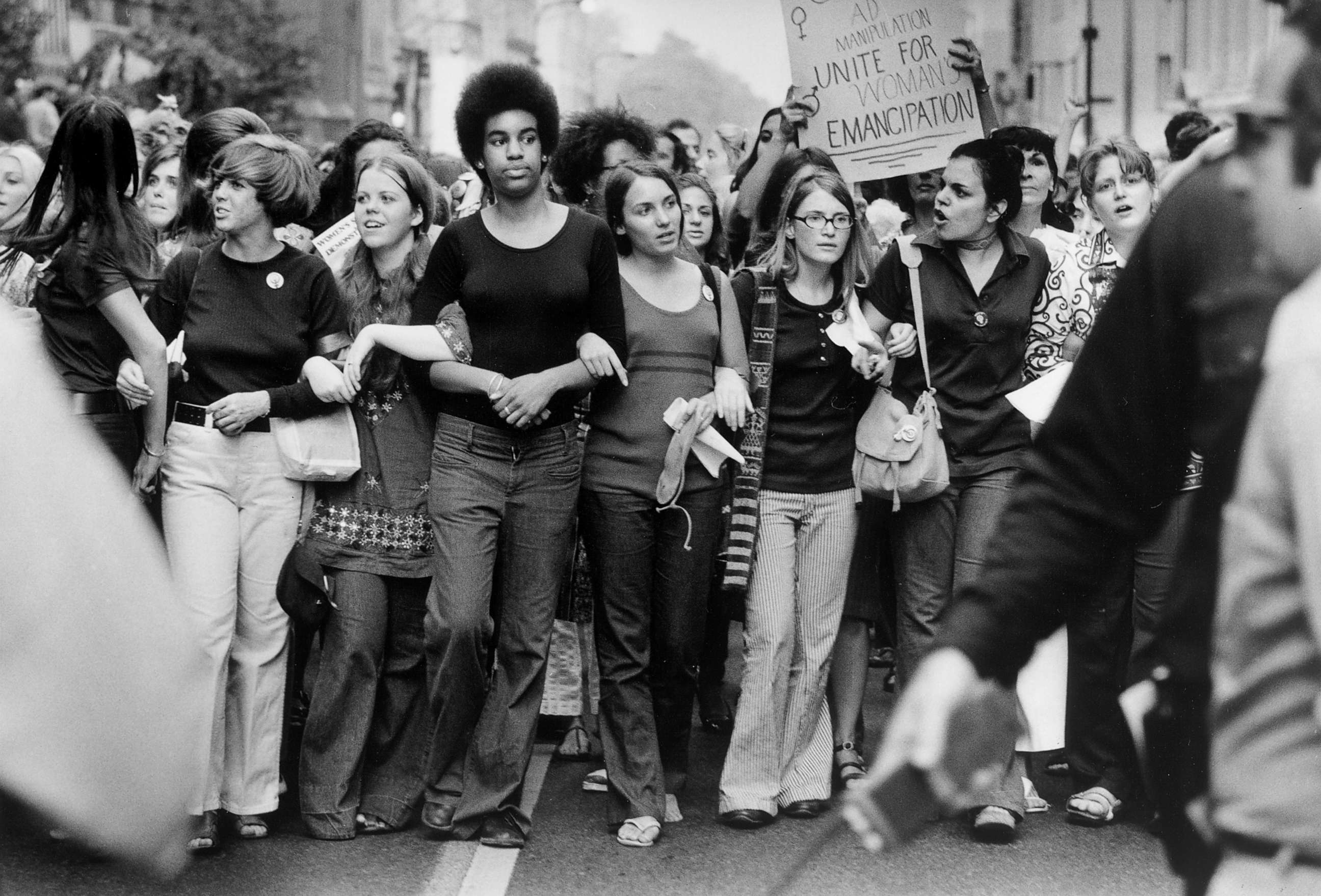

Research shared as early as the 1970s showed how in U.S. high school history textbooks, "Women are rarely shown fighting for anything; their rights have been 'given' to them" and that the book's authors "select male leaders and quote from male spokesmen."

Even in texts that had been updated at the time to reflect black history, they had not "made room for the black woman," the research found.

If textbooks are updated, the average school does not get a new set of textbooks every year, according to Sharkey, executive director of the AAE.

State standards that don't capture the full picture of women's role in history don't help either, as NWHM's research found. Another conflict is the idea that if more history about women goes in a book, something else must come out.

"All history projects require choices. Including a person or event excludes another," the authors of the NWHM report wrote. "Women often don’t make the cut."

Sharkey said his organization found that TV shows and movies are often the most effective tools teachers end up with to teach about women's role in history. Recent films like "Hidden Figures," which told the story of three African-American women at NASA, and "Confirmation," which tells the story of Anita Hill, are among the Hollywood projects that have shed a new light on women.

"A series about a time period, like 'Downton Abbey,' that exists that reveals a certain slice of history at that time generates a lot of content quickly and most of it’s free and it’s popular and topical so teachers don’t have as much challenge introducing it to the kids," Sharkey explained.