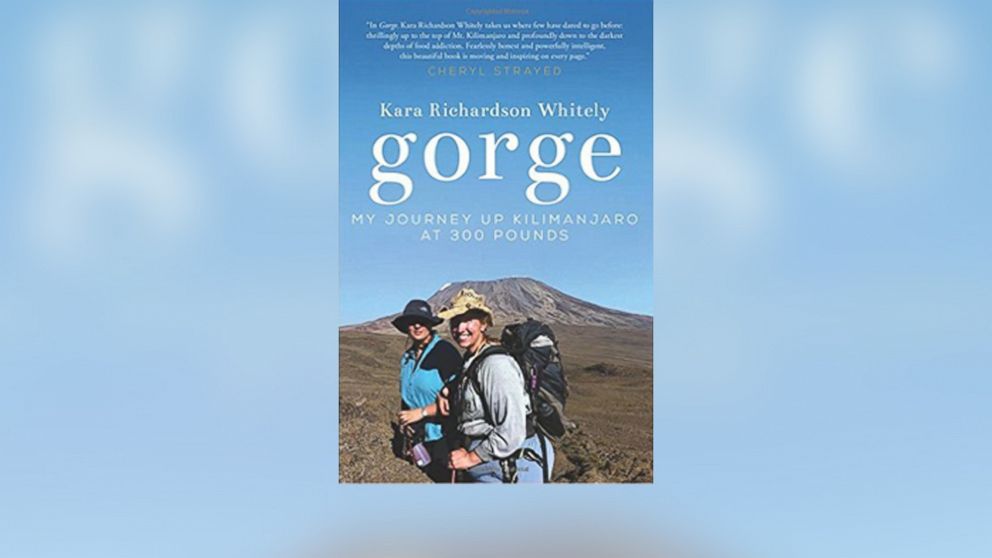

Woman Recounts Climbing Mt. Kilimanjaro at 300 Pounds in New Book

— -- Climbing Tanzania’s Mount Kilimanjaro can be brutal for anyone, but Kara Richardson Whitely’s weight made it even more so.

Whitely, who weighed 300 pounds, described the 2011 climb, her third up the famed mountain, as being “like hiking the mountain with someone on your back.”

Whitely’s first trek up the dormant volcanic mountain, in 2007, had been a triumph. The 32-year-old New Jersey woman had lost 120 pounds, getting down to a weight of 240 pounds, and she was eager to celebrate her success.

“Everybody was focusing on how much weight I had lost. And it was great. It was an amazing adventure. My husband and I both summited together,” she said in an interview with ABC News’ Juju Chang.

One year later, and by then a new mother, Whitely regained more than half of the 120 pounds she’d worked so hard to lose. And then she went back to Kilimanjaro.

“I was really in a dark place. And I wanted to get myself out. But … I didn't do the work that was necessary to end up on top of the mountain again,” she said.

In 2011, she set out on a third climb of Africa’s tallest mountain, while weighing 300 pounds.

Guides on the ascent actually bet against her, but she stood up for herself and she proved them wrong. She reached the peak of Kilimanjaro.

“I felt tremendous gratitude for the journey that I had taken … and there was a knowing at that moment that I was the one who had to decide which baggage I would continue to carry with me. And I'm not talking about my backpack,” she said.

Whitely, a public speaker, has chronicled her personal battles, including her struggle with weight, in the book “Gorge: My Journey Up Kilimanjaro at 300 Pounds.”

Whitely’s weight problems are rooted in personal trauma. As a 9-year-old, she dealt with her parents’ divorce by hiding in the pantry and comforting herself with snacks.

Asked why people binged in secret, Whitely replied: “Well, it's about not feeling. Binging is about swallowing your feelings, really. I would binge in private because then I wouldn't have to feel the hard stuff, or even the happy stuff.”

During a sexual assault when she was 12, Whitely says she offered her attacker something to eat. The offer ended the assault.

In her book, she wrote that food saved her.

“Maybe food saved me for a time. But like a lot of bad habits or addictions … it became the thing that consumed me,” she said.

Whitely finally realized that, instead of radical weight loss, she needed smaller, sustainable victories to keep her obsessive eating under control.

And yet, Whitely says the struggle is never really over.

“Your book doesn't have a fairy tale ending,” Chang said. “You don't, you know, miraculously end up a size zero.”

“Right,” Whitely replied. “And I wrote the book to give a true feeling of what it's like to struggle with weight. And that's actually what I'm finding a lot of people love about it, is it doesn't have that ending. It's a realistic story of the experience.”