White neighborhoods have more access to COVID-19 testing sites: ANALYSIS

When the coronavirus outbreak threatened to rock Philadelphia’s predominantly Black neighborhoods, Dr. Ala Stanford knew that access to COVID-19 tests was going to be a problem.

So she rented a van, loaded it up and headed to the areas of the city where residents needed tests the most. Every test conducted was free.

When Stanford began distributing tests in early April, she saw only a handful of testing centers in the city. Only a small share were in majority-Black neighborhoods and the bar for actually getting a test was high.

“We’ve been to locations that are predominantly African American where everyone had insurance and they couldn’t get tested,” Stanford said referring to the often strict requirements providers had of those seeking tests as the outbreak began, such as doctor referrals, appointments and symptoms consistent with infection.

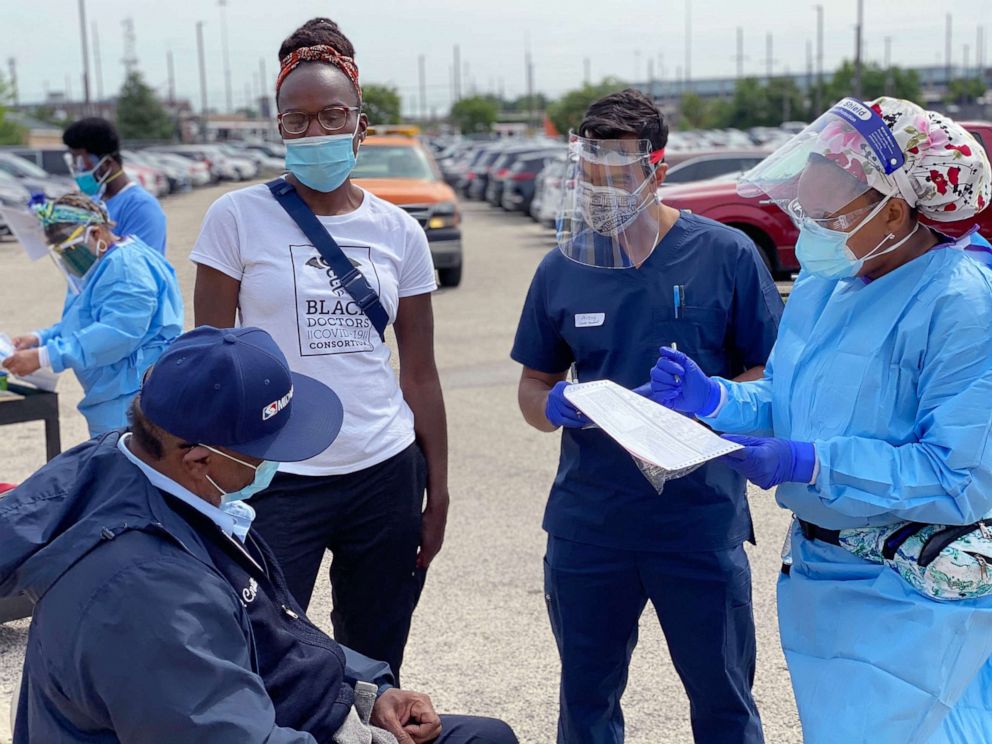

Stanford, a pediatric surgeon, quickly assembled a group of doctors and volunteers called the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium to help meet the challenge of testing the city’s underderserved residents. Together, the group has issued Philadelphia’s residents more than 7,000 tests. But even with the intervention of medical professionals like Stanford stepping in to meet the rising demand, many communities of color across the country still face a dire situation in terms of getting a COVID-19 test.

With nearly 4 million coronavirus cases across the United States and hospitalizations surging in different parts of the country, there continues to be a growing demand for COVID-19 tests. Currently, Americans routinely wait for hours to get an exam — if they can get one at all. Access is not available equally nationwide.

Simply put, where Americans live and how much income they earn can still determine the ease with which they get a COVID-19 test.

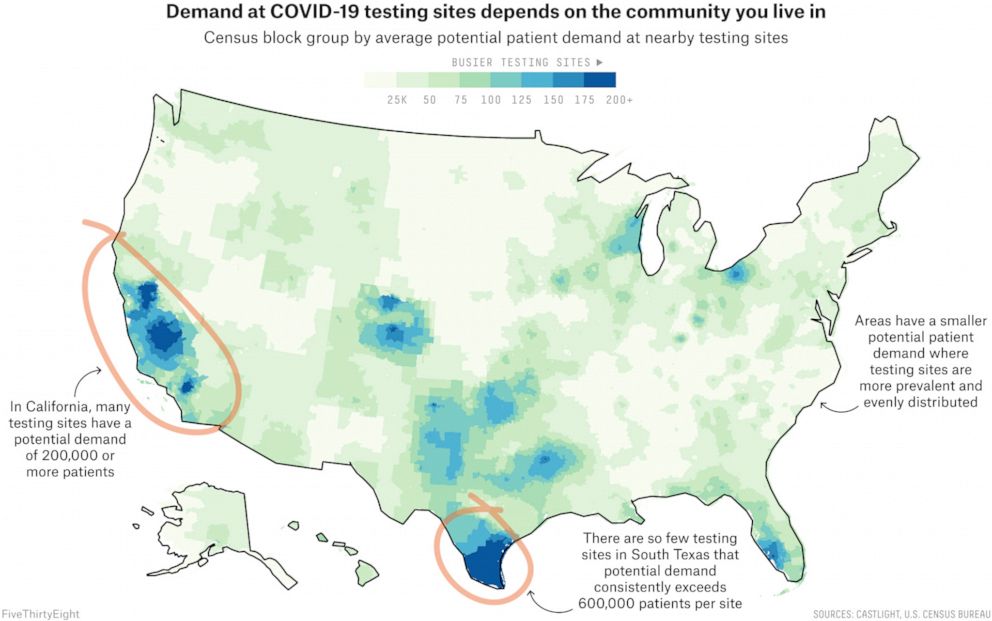

According to a new, extensive review of testing sites by ABC News, FiveThirtyEight and ABC-owned television stations, sites in communities of color in many major cities face higher demand than sites in whiter or wealthier areas in those same cities. The result of this disparity is clear: People of color, especially Blacks and Latinos, are more likely to experience longer wait times and understaffed testing centers.

This nationwide review is one of the first to look at testing site locations coast to coast, in all 50 states plus Washington, D.C., using data provided by the health care navigation company Castlight Health (the same data that Google Maps uses to surface COVID-19 testing sites). An assessment of city and state health department websites also revealed, over and over, fewer testing sites in areas primarily inhabited by racial minorities.

Importantly, our analysis does not factor in the capacity of testing sites -- which can vary from just 50 tests at one site to 2,000 at another, meaning that one site might be equipped to serve a larger number of people than another site. Instead, it looks at the potential demand for each site based on the number of people and sites nearby. The data we used also is less likely to reflect tests done in private physicians’ offices than federally-funded community sites, local government-run mobile pop-up sites, urgent care clinics and hospitals. The analysis also doesn’t take into account other factors that could determine testing accessibility, such as staffing and wait times, as well as other restrictions on testing like appointment or insurance requirements.

When the outbreak began, testing posed the most immediate challenge to states, as a shortage of supplies, testing kits and processing backlogs created capacity problems. Since then, states have vastly increased their bandwidth to perform tests, but even now, experts from the Harvard Global Health Institute say daily testing needs to be nearly doubled to mitigate the pandemic. And states and cities are still struggling to determine how to allocate testing resources and where to place testing centers.

The Trump administration struggled early on in the pandemic to expand testing nationwide. Reliant on off-shore manufacturing that limited access to supplies like swabs and reagents, and armed with little data about who was getting sick and where, Trump’s political appointees quickly embraced that the federal government’s job would be mostly managing the logistics of testing such as supplies and distribution of state funds, as opposed to overseeing the coordination of state testing plans.

But critics say that strategy left many states scrambling to meet the rising demand that health experts say will only grow more urgent in the fall, when students return and flu season starts.

The Department of Health and Human Services recently released a comprehensive strategy to address the disparate access to COVID-19 testing, including expanding testing at federally qualified health centers as well as supporting public-private partnerships that establish testing at retail pharmacy companies to accelerate testing within vulnerable populations. CVS and Walgreens -- two of the retail pharmacies listed in the HHS plan -- both said in statements to ABC News that more than half of their store locations issuing COVID-19 tests are now located in areas most in need, based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s social vulnerability index.

HHS also says it’s working to get more data on who is getting sick – a longtime challenge because most health care data resides in privately run hospitals and doctors. As of Aug. 1, labs will be required to report the race and ethnicity of COVID-19 test patients, months after an ABC News and FiveThirtyEight investigation found at least 19 states and U.S territories were missing data critical to understanding which communities were seeing the most fatalities from the novel coronavirus. The agency says they cannot assess the efficacy of their strategy to reduce the testing disparity until they get additional demographic information on COVID-19 test patients.

“Requiring this level of detail in reporting of COVID-19 test data is a significant change for labs and especially for labs that may not operate with electronic reporting systems,” said an HHS spokesperson. “Once implemented, this guidance will rapidly advance the public health system reporting structure that has been lacking modernization for years.”

What our analysis found

The novel coronavirus itself does not distinguish between Black and white Americans. But virtually every other aspect of U.S. society does, including the nation’s response to COVID-19.

Our analysis revealed that, in many cities, testing sites in and near predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods are likely to serve far more patients than those near predominantly white areas.

A similar disparity exists between richer and poorer neighborhoods, our analysis showed: Testing resources were more scarce in poorer areas, with fewer sites per person and sites located farther away. And the disparity could be even higher in real life, considering wealthier people could also get tested by private practitioners who are less likely to be reflected in our analysis.

Kevin Ahmaad Jenkins, a fellow at the University of Pennsylvania’s Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics who has been researching the impact of COVID-19 testing center availability on communities of color, told ABC News and FiveThirtyEight that his team found that testing sites serving minority communities in big cities are fewer in number, have longer lines and often run out of tests. The impact of such disparities, he said, is evident in the pandemic’s disproportionate effect on people of color.

“It’s just as clear as George Floyd’s video. These numbers are right in front us: We are dying at disproportionate rates,” he said.

To better understand the extent of this problem, we looked for cities whose broader “urbanized area” had at least 1 million residents. (“Urbanized area” is a census designation for cities and the densely populated areas immediately surrounding them.) We then calculated the potential level of demand at each testing site in that area, based on the number of people living nearby and additional sites in the area.

We assumed that people would want to get tested at nearby sites, so we compared the number of patients a site would serve if the population of each census block group tried to visit sites that were close to them. This value, which we will refer to as potential patient demand, reflects how many people live near a given site and how many other options those people have.

The disparities we found varied in severity across the country. In some major urbanized areas, they’re small or nonexistent. But in others -- from Dallas and Miami to San Diego and many places in between -- majority-Black and majority-Hispanic neighborhoods faced far more competition for COVID-19 testing than their white neighbors. Disparities were also seen in some predominantly Asian or Pacific Islander communities, such as those in Washington, D.C., Minneapolis and Riverside, Calif., but they weren’t as widespread as those among Black and Hispanic communities.

Read more about our findings:

And our calculation of potential demand for testing at some sites in those underserved neighborhoods is likely an underestimation: Based on our reporting, many of the testing sites in those neighborhoods are government-funded community sites set up to close the gaps in testing access in different communities, but they tend to be very popular among people from all across the county or urban area because they are often free and don’t require an appointment.

We used data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s 2014-18 American Community Survey five-year estimates to figure out if, within urbanized areas, block groups that were majority Black or majority Hispanic were more likely to be close to sites with higher potential patient demand than majority-white block groups. To compare neighborhoods, we created a measure that we call potential community need, which is an average of the potential demand at nearby test sites. We also examined how block groups with a median income in the top 25 percent compared to those with median incomes in the bottom 25 percent.

Castlight’s set of testing site locations is among the most comprehensive data available, but compiling every testing location in the nation is a massive undertaking, as sites are constantly opening, closing and moving. Given that, the data set is likely missing some testing sites. Additionally, our analysis is based on testing site data as of June 18, so many new sites have been added nationwide since then -- and others have likely closed or moved. We conducted separate analyses using a different source of testing site locations and examined other testing-related data to corroborate our findings.

We’ve highlighted some of the cities with the most emblematic trends below. While we’re confident in the trends we’re presenting, we’d encourage you to think of them more as estimates (akin to a fire marshal’s approximation of the size of a crowd at a political rally) than exact measurements (such as a baseball player’s batting average). For more detail on our methodology, and some of the limitations in the data and thus this analysis, see here.

However, this analysis still provides a vivid snapshot of the hurdles, complications and shortfalls in American efforts to slow the spread of COVID-19 this summer, a time when increased testing capacity in minority and low-income areas could have slowed the disease — a point widely acknowledged by public health experts.

“Testing site distribution and capacity is a direct reflection of the inequalities in our existing health care system,” said John Brownstein, a professor of epidemiology at Harvard Medical School whose team of researchers at Boston Children’s Hospital’s Computational Epidemiology Lab also looked into the health care disparities underlying geographic access to testing. “The lack of access for those most vulnerable to infections will only serve to intensify the impact of this pandemic.”

For Dr. Ala Stanford and her colleagues at the Black Doctors COVID-19 Consortium in Philadelphia, the choice early on was clear: adjust to a new normal of life indoors, or move swiftly to implement testing on the streets of Philadelphia to combat a virus that was proving deadly to Black communities.

Stanford says she felt compelled to respond as she did because she knew that the same health care disparities she learned about in medical school, and as a practicing doctor, were still at play in Philadelphia during the coronavirus crisis -- the city in which she’s spent her entire life.

“I stopped and said to myself: I’m a business owner in private practice, I have access, I can order these lab kits like anybody else, I know where the people are that are hurting,” she said. “And I am not afraid to go there.”

Laura Bronner is FiveThirtyEight's quantitative editor

Grace Manthey, a data journalist for ABC Owned Television Stations in Los Angeles, ABC News’ Briana Stewart and FiveThirtyEight’s Rachael Dottle contributed reporting.