These vaccine mandates are already in place to attend school in the US

By early next year, all eligible students attending a Los Angeles public school will be required to be fully vaccinated against COVID-19.

The school district is the largest in the country to mandate the shot -- which joins a list of other vaccines already required to attend school that protect against highly contagious diseases.

All 50 states and the District of Columbia have vaccine requirements for children to attend school and child care facilities, including laws around allowable exemptions.

Massachusetts became the first state to enact a school vaccination requirement in the 1850s for the smallpox vaccine -- the first immunization developed against a contagious disease -- according to a publication by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Other states followed suit, and by the 1980-1981 school year, all states had vaccination requirements for students entering the classroom, the CDC said.

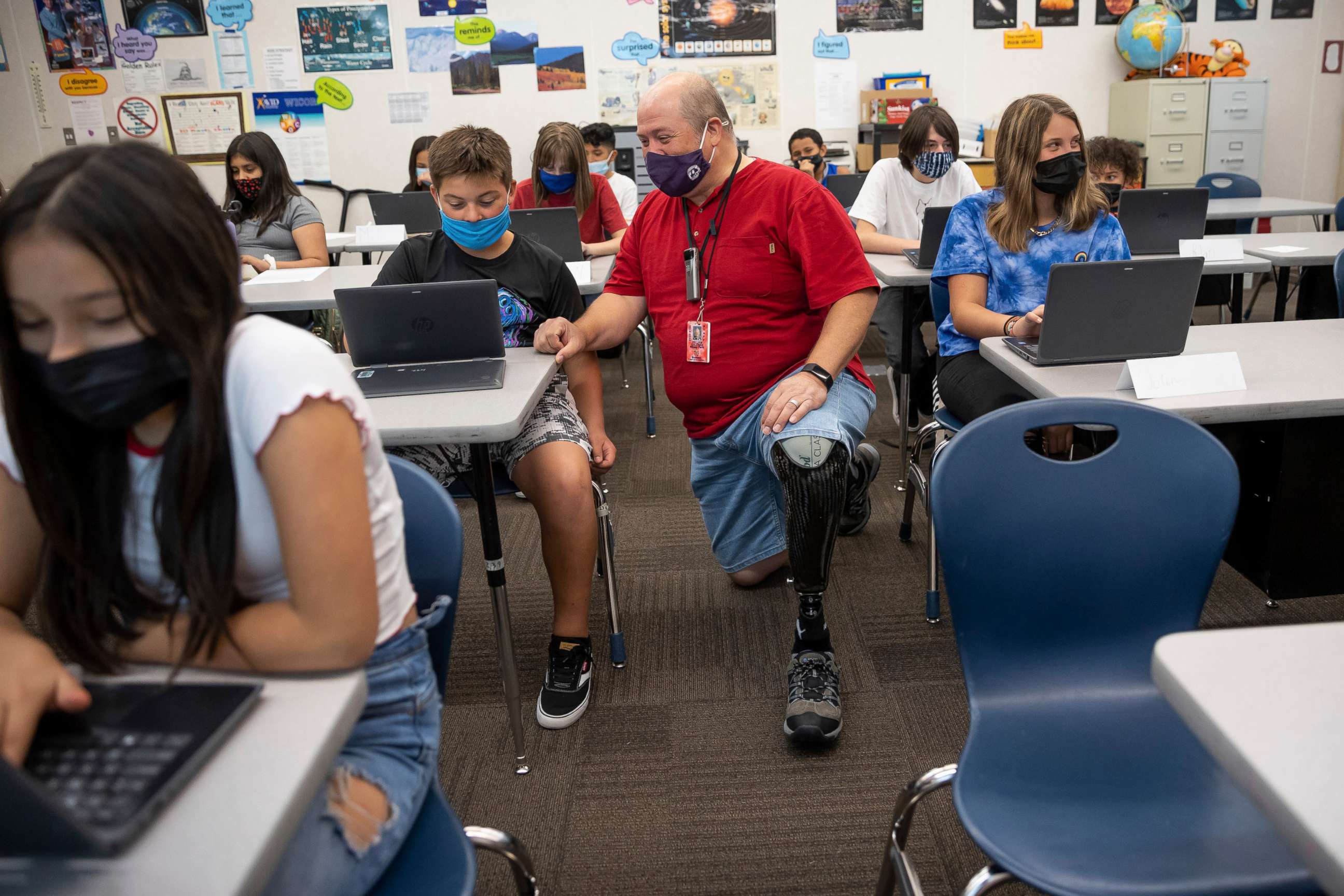

Children in close proximity with poor ventilation and hygiene practices can lead to "transmission events," said Dr. John Brownstein, an epidemiologist at Boston Children's Hospital and an ABC News contributor.

"This is why vaccine mandates in schools have been super important," Brownstein said. "They create a safe environment where you can recognize that you will not have transmission of a wide range of infectious diseases like measles, mumps, rubella, whooping cough."

The mandates have been "very successful" in preventing outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases, he said.

Thanks to vaccination efforts, many highly contagious diseases that were once common, such as measles, mumps, whooping cough (aka pertussis) and chickenpox, are now rare, while polio and smallpox have been eradicated in the U.S. Routine child vaccination is estimated to prevent 936,000 premature deaths and 419 million illnesses in American children born between 1994 and 2018, according to the CDC.

Vaccine mandates for child care and schools vary by state. All require vaccines that protect against polio, diphtheria, tetanus, whooping cough, measles and rubella, according to the Immunization Action Coalition (IAC), a vaccine education and advocacy organization. Nearly all states require vaccines that protect against mumps, chickenpox, hepatitis B and pneumococcal disease.

Vaccines that aren't widely required by states include ones for the flu, hepatitis A, rotavirus and HPV, according to IAC. The U.S. stopped routine vaccination for smallpox -- which has been eradicated globally -- in the 1970s.

"Precedents have been set that you can protect your community by requiring school vaccination requirements," L.J Tan, chief policy and partnerships officer for IAC, told ABC News.

For the 2019-2020 school year, about 95% of children in kindergarten in the U.S. had received the DTaP (diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis), MMR (measles, mumps and rubella) and varicella (chickenpox) vaccines, according to the CDC, with roughly 5% exempt from or not up to date on certain doses.

The agency has observed a decrease in vaccination rates during the pandemic, as COVID-19 has disrupted school and routine well visits for many families. There was a 14% drop in public sector vaccine ordering in 2020-2021 compared to 2019, and measles vaccine ordering decreased by over 20%, the CDC reported.

The decline in routine pediatric immunizations has been very concerning for public health experts.

"Whenever we have a decrease in coverage, that could be an opportunity for these infections to reemerge and cause outbreaks -- and one of the most obvious, recent examples is measles," Dr. Flor Munoz, a pediatric infectious disease specialist at Texas Children's Hospital and Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, told ABC News.

In 2019, the U.S. saw its largest measles outbreak in 25 years, with 1,282 cases confirmed in 31 states, mostly among people not vaccinated against the virus, according to the CDC.

It's especially important that children stay up-to-date on vaccines as many return to in-person learning and routine activities, Munoz said.

"All of these other diseases that are vaccine-preventable can reemerge at any time," Munoz said. "Vaccination is the easiest way and the best way to prevent any of these potentially serious infections."

Pediatric COVID-19 rates have reached record levels in the U.S. as students return to school. In the last two weeks, nearly half a million children have tested positive for COVID-19, according to the latest report on pediatric coronavirus cases from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children's Hospital Association.

Pfizer's COVID-19 vaccine is authorized for people as young as 12 and approved by the Food and Drug Administration for those ages 16 and up. The pharmaceutical company has said it plans to submit vaccine safety data on 5- to 11-year-olds to the FDA by the end of September.

Currently, no state requires the COVID-19 vaccine for children ages 12 and older for school entry, though some are mandating it for certain state employees and many colleges are requiring it for students. At the same time, at least nine states have barred schools from mandating that students get the vaccine, including Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas, according to the Associated Press.

The Los Angeles Unified School District's Board of Education last week approved a mandate that students ages 12 and up be fully vaccinated against COVID-19 by Jan. 10, 2022, to attend class in-person. At this time, the school district said it is not requiring booster shots, which the Biden administration is planning to be made available as soon as next week for the general public at least eight months after their second dose.

Beyond Los Angeles, nearby Culver City is mandating that public school students get the vaccine this school year, and two San Francisco Bay Area districts are considering the same. More school districts may likely follow suit, creating a "domino effect," Brownstein said, especially as younger children become eligible to get the vaccine.

"A safe vaccine that can prevent transmission, protect our kids and ensure that they can stay in in-person learning actually makes a lot of sense," he said. "And there's historical precedent for doing so."