An unusual patient, an unusual treatment: Trump and the risks of 'VIP syndrome'

With unlimited access to resources and the nation's finest physicians by his side, President Donald Trump may reasonably expect to be treated with a higher level of care and attention than the average American infected with COVID-19.

Experts say that may not be a good thing.

On Friday, after the White House revealed that the president had been given an unapproved but promising antibody cocktail, medical professionals warned that his special treatment, known colloquially in medical circles as "VIP syndrome," may have adverse effects.

"When a patient is high profile, there's a temptation to break away from the standard medical care that you would give to any other patient -- and sometimes to the disadvantage to the patient, the VIP," said Dr. Mark Siegel, a Yale academic and physician.

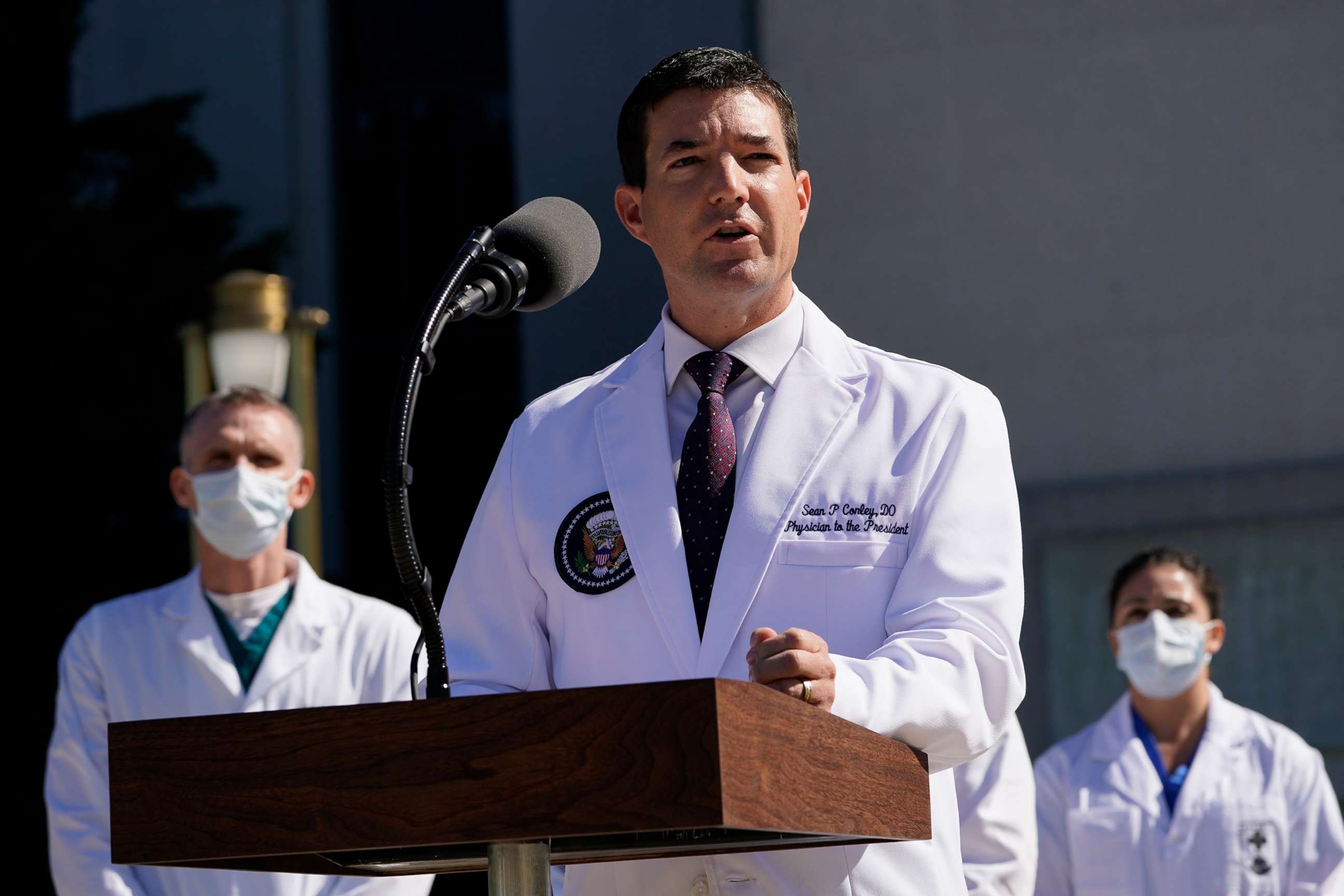

Dr. Sean Conley, the president's personal physician, said at a Saturday press briefing that Trump is "receiving all the standard of care and beyond."

"We are maximizing all aspects of his care, attacking this virus with a multi-pronged approach," he said. "I didn't want to hold anything back. If there was any possibility that it would add value to his care and expedite his return, I wanted to take it."

Shortly before Marine One swept the president off to Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland, on Friday, the White House announced that the president had been administered a dose of an unproven antibody therapy developed by drugmaker Regeneron.

Regeneron's treatment has not been authorized by the Food and Drug Administration. The company said in a statement that the president was granted approval to use it as part of a "compassionate use" clause, which clears the way for legal access to an experimental drug outside of a clinical trial.

Experts said there's evidence the antibody cocktail may improve the president's condition, but it carries the risk of producing unexpected side effects.

Regeneron CEO George Yancopoulos told ABC News late Friday that the antiviral cocktail Trump received, which he said may provide antibodies for up to two months, has only been issued for compassionate use in "a handful of cases ... on the order of 10 or less."

Siegel, the Yale physician, said that for typical coronavirus patients with "mild symptoms" -- that's how the White House characterized Trump's -- physicians "generally don't do anything other than general supportive care," making the president's robust drug regimen and hospitalization a bit unusual.

Dr. Lew Kaplan, president of the Society of Critical Care Medicine and a surgeon at the University of Pennsylvania, warned that these types of "non-standard processes, they invite error."

"One of the swiftest ways to have things go awry is to be treated as a special person," Kaplan explained, "because it derails the usual process."

Mitchell Levy, chief of pulmonary critical care at the Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University and a COVID-19 treatment guidelines panel member, said that because of Trump's status, doctors are "sort of cracking out everything."

"They are administering a lot of unproven therapies to the president of the United States," Levy added. "All I can say is, I would never use that stuff in my ICU."

Others are less concerned. Dr. Gerard Criner, who's treated novel coronavirus cases as part of Regeneron's ongoing clinical trial at Temple University in Philadelphia, said "hundreds of patients" have responded well to the Remdesivir and cocktail combination "without obvious concerns."

Unlike the Regeneron cocktail, Remdesivir has been formally reviewed by the FDA, which issued emergency-use authorization based on evidence it can shorten the duration of symptoms in some patients.

Neither treatment has been granted full FDA approval, which takes much longer.

One notable omission from the president's current treatment regimen is hydroxychloroquine, an anti-malarial drug that Trump once promoted -- and even used as a prophylactic -- despite any evidence of its efficacy. Early on in the pandemic, some infectious disease experts hoped it might emerge as a silver bullet cure, but that was never the case.

Conley said Saturday that Trump "asked about [hydroxychloroquine], and he's not on it now."

Siegel said the president's aggressive treatment plan may reflect an effort by his medical staff "to do more rather than pull back, for fear of being criticized" -- another potential side effect of VIP syndrome.

The president remained hospitalized on Saturday, with his physicians saying he was "doing very well." His treatment includes a five-day regimen of Remdesivir.

"If famous people get all treatments that may not be necessary," said Dr. Martin Tobin, a professor of medicine and critical care physician with the Loyola Health System, "they could do worse than the average person."

Remdesivir, for example, has been shown to negatively affect some patients' livers.

While most of the drugs the president is taking, including zinc and vitamin D, are "probably innocent," Tobin added, "the use of the Regeneron monoclonal antibody is in a different category."

"This medication has undergone very limited clinical testing," he continued. "If Mr. Trump incurs serious complications from Regeneron, he will join the list" of high-profile patients adversely affected by VIP syndrome.