Unions, advocates say Trump putting meat packing workers at risk

Union officials and worker advocates are sounding the alarm about the president's latest move demanding the meat packing industry stay open during the COVID-19 pandemic, saying workers are already at risk of getting sick and companies have not done enough to protect them.

Meat packing plants across the country have been closed amid outbreaks among workers operating in close conditions, including one of the largest outbreaks in the country at a facility in South Dakota.

Industry officials have publicly raised concerns that more closures would threaten the supply of meat to consumers and hurt farmers who would have nowhere to send their livestock but that they're being pressured to close by local officials to minimize the impact of outbreaks.

President Donald Trump's executive order pushes those plants to stay open to maintain the supply of meat for consumers and provides cover to companies facing pressure to stop production to prevent COVID-19 outbreaks. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, which is now in charge of coordinating with companies, says it will still require them to follow the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Occupational Safety and Health Administration recommendations but advocates are concerned workers could still be exposed to the virus.

"The government cannot force these workers to work with that -- the basic essential protections, like, that is just not right," Magaly Licolli, an organizer for workers in meat processing plants in Arkansas, told ABC News. "You know, you don't send a military to the war without guns, you know, and so that is not what the workers want. The government and this company just want to keep sacrificing workers for their profits."

Tune into ABC at 1 p.m. ET and ABC News Live at 4 p.m. ET every weekday for special coverage of the novel coronavirus with the full ABC News team, including the latest news, context and analysis.

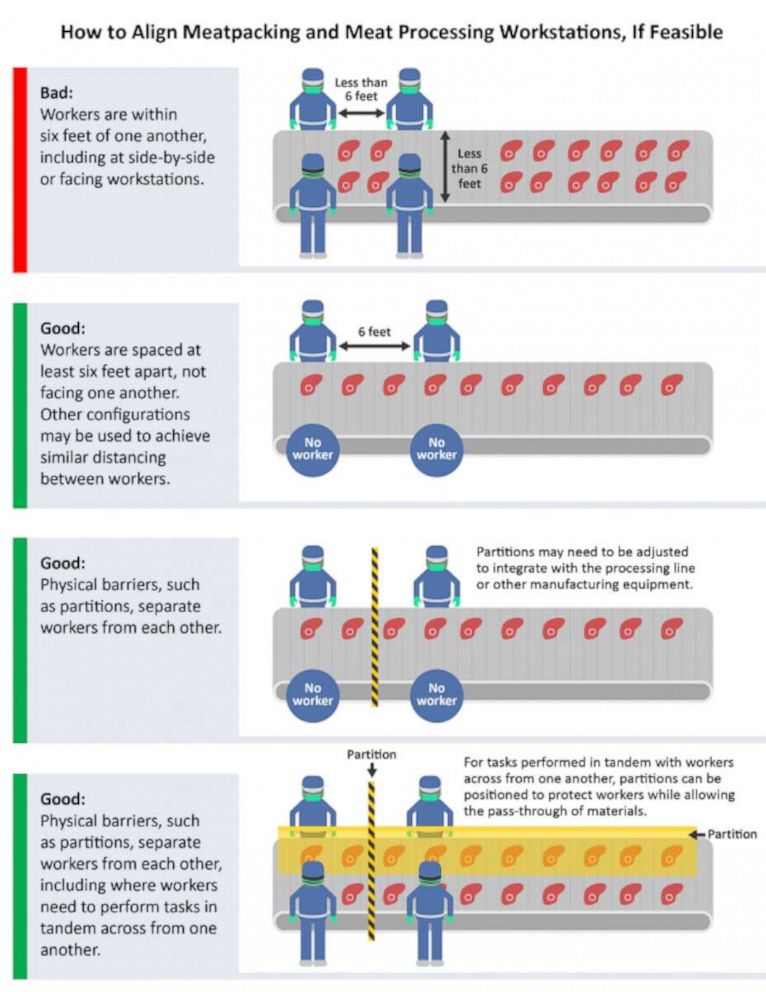

Companies such as Tyson Foods say they have implemented some of the social distancing guidelines by installing partitions between workstations, taking employee temperatures and other changes, and the new executive order puts the Department of Agriculture in charge of working with companies to enforce them as they keep working.

But advocates like Licolli said it isn't enough. She said despite what companies say publicly, workers have told her that they still take bathroom and meal breaks as a shift and social distancing is not enforced or steps that have been implemented, such as adding plastic barriers between work stations, were done too late.

"The workers are already getting sick and they are not being protected. And so what they're basically doing with this is telling Trump to protect them from their workers," she said.

The national union that represents workers in meatpacking and food processing jobs, the United Food and Commercial Workers, says the administration should enact enforceable standards instead of guidance that requires protections like protective equipment, physical distancing, daily testing for workers and paid sick leave so workers can stop the spread of illness.

And Richard Trumka, president of the AFL-CIO, echoed their concerns tweeting, "Using executive power to force people back on the job without proper protections is wrong and dangerous."

The conditions in a meat processing plant already make it difficult to follow the CDC's social distancing guidelines. Workers are close together on the line and reaching out to break down carcasses into smaller cuts of meat, making it hard to avoid coming in contact with other workers.

CDC and OSHA put out guidelines to address these concerns and the president's executive order puts Agriculture Secretary Sonny Perdue in charge of coordinating with companies to reopen or stay open during the pandemic, but there are still no requirements that force companies to implement changes, which could cost millions of dollars to reconfigure facilities and equipment.

OSHA said in a statement it could still enforce some violations of the guidance for meat processing companies and that the president's executive order doesn't mean plants can be forced to close or open by local officials without adhering to those standards. The agency also said recorded compliance with the standards could work in a company's favor if they are sued for workplace exposure to the virus.

USDA says it will work with meat processing companies to "affirm they will operate in accordance with the CDC and OSHA guidance" and with local officials to reopen facilities that have closed. In a statement Wednesday a USDA spokesperson said the agency will still require facilities to comply with the social distancing guidance and that a team of officials from multiple agencies will review written plans for each facility to protect workers from exposure to COVID-19.

"Under the order, the Department of Agriculture is directed to ensure America’s meat and poultry processors are able to continue to operate uninterrupted to the maximum extent possible. USDA is directing meat and poultry processing plants to operate in accordance with the CDC/OSHA Guidance for Meat and Poultry Processing Workers and Employers to facilitate ongoing operations, while mitigating the risk of spreading COVID-19," the spokesperson said in a statement.

"The USDA-led federal leadership team will swiftly review documentation provided and work in consultation with the state and local authorities to resume and/or ensure continuity of operations at these critical facilities.”

So how did this situation that seems to pit having a consistent supply of meat against the well-being of the workers who produce it occur?

Experts say it's because the pandemic has highlighted flaws in the existing system to process meat, including that it relies heavily on its workforce which is concentrated in large facilities managed by a few large companies.

Miguel Gomez, an assistant professor of economics at Cornell University said it's difficult to develop social distancing protocols for large plants and that even though it's important to keep up production capacity the situation will only be worse if more workers get sick.

"That's a very, very tough -- tough situation because yes you want to keep the -- the supply, you know supply -- especially in this case for meats -- open but the problem is that is so labor intensive," he told ABC News.

Gomez said the number of large companies in the U.S. has made the food system very efficient and cheap for consumers in this country, but that the downside is disruption can have huge ripple effects.

"It has become so concentrated so that the cost of production goes down, industry concentration in beef, in the -- in the chicken supply chain, the pork supply chain, even in fresh produce is so huge, that you know you have a problem in one of these large operators and then you feel the impact, nationally."

Other experts like Patrick Stover, vice chancellor of Texas A&M AgriLife, said it's important to keep up production to protect companies and farmers for the future and keep food prices down, but that the industry also needs to adapt.

"The virus has really put a spotlight on vulnerabilities that have been there, but not realized, because the system was never put under stress. So, for instance, the reliance on a labor force that -- a labor force that is not always predictable and can be precarious at times," Stover said, adding that automation and other technology could make the system less dependent on workers.

Gomez said automation in meat processing is more of a long-term goal but the current crisis should force some reflection on how to make our food supply chain more resilient and flexible, including redesigning factories to protect workers and supporting mid-range businesses to better compete with large companies, even if that means consumers may pay more at the grocery store.

What to know about the coronavirus:

- How it started and how to protect yourself: Coronavirus explained

- What to do if you have symptoms: Coronavirus symptoms

- Tracking the spread in the U.S. and worldwide: Coronavirus map

Phil Yacuboski reports for ABC News Radio: