A look at Trump's economic legacy

President Donald Trump campaigned as a billionaire businessman and champion of the working class with the economic prowess and deal-cutting skills that politicians in Washington, D.C., lacked.

He summed up his position neatly during the campaign: "I'll be the greatest jobs president that God ever created."

On the campaign trail, Trump claimed to be laser-focused on bringing back manufacturing and mining jobs, renegotiating trade deals that led to work disappearing overseas and curtailing immigration.

His Clintonian tack of "it's the economy, stupid," despite the myriad scandals and investigations that dogged him, largely worked as GDP grew at a healthy clip, the stock market soared and unemployment rates hit a half-century low, until the coronavirus pandemic gutted the job market.

Yet as he leaves after his one-term tenure, Trump has become the first president since Herbert Hoover during the Great Depression to depart office with fewer jobs in the country than when he entered.

Economists say Trump’s economic legacy will be defined by his failure in leadership during the COVID-19 pandemic that exacerbated the financial downturn, domestic policies that overwhelmingly benefited the wealthy, and international trade policies that hurt U.S. industry while simultaneously alienating allies.

By attempting to implement economic policy through the so-called "art of the deal" and ignoring lessons that many economists have learned over the last 50 years -- such as the importance of Fed independence, the effects of large budget deficits on trade deficits, the value of multilateral institutions such as the World Trade Organization and more -- he failed to achieve his own self-proclaimed goals of reducing the trade deficit with China, controlling the national debt or strengthening the American manufacturing sector.

Here is a look at the outgoing president's legacy on the U.S. economy.

Coronavirus response

Trump inherited an economy from the Obama administration that was expanding, and it continued to do so during the first three years of his presidency. While real wage growth was slow or stagnant for most Americans, and had been under Obama, unemployment continued to trend downward and GDP continued to grow.

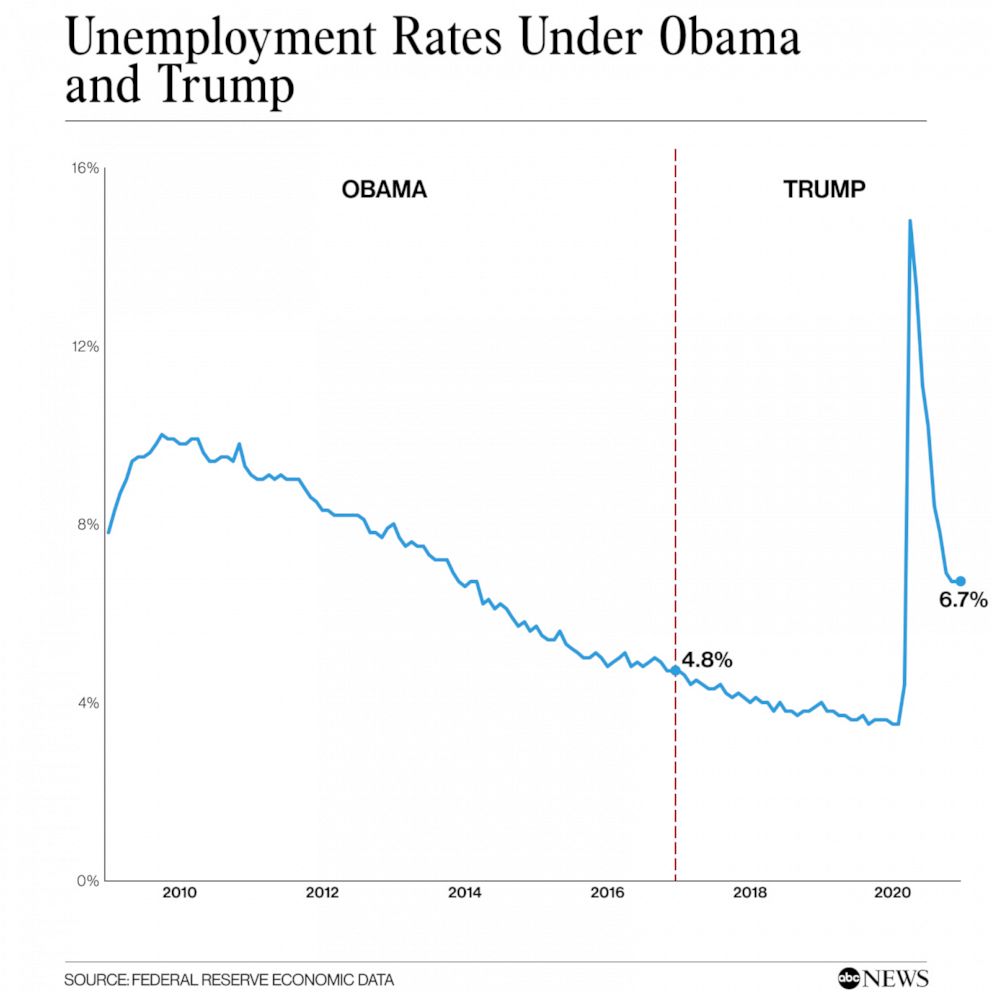

In the last year of Trump’s presidency, the unemployment rate reached a 50-year low of 3.5% in February. The coronavirus pandemic soon walloped the economy, forcing swaths of businesses across the country to close. The unemployment rate skyrocketed to 14.7% in April. It receded to 6.7% as of last month but remains above the level of 4.8% when Trump took office in 2016.

Moreover, millions of jobs lost during the pandemic may not come back anytime soon.

As the pandemic raged in the U.S., however, Trump consistently downplayed its severity. Instead of focusing on getting the virus under control, he concentrated on reopening the economy and several surges in the virus followed, including the most severe as he leaves office.

The lack of leadership during the health crisis was not only deadly -- with thousands of Americans dying every day -- but also disastrous for the economy. Other countries such as China and South Korea were better able to control the spread of the virus. As a result Chinese GDP is forecasted by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development to increase by 1.8%, and Korean GDP is forecasted to fall by only 1.1% -- considerably less than the 3.7% drop forecast for the U.S.

The Chinese Communist Party's ironclad pandemic response was notably much stricter than many democratic nations including the U.S. The U.S.'s GDP forecast is on par with G20 nations, which all together are forecast to have a 3.8% drop in GDP.

“There are many countries that have made mistakes, but there are some countries that have done it right,” Jeffrey Frankel, James W. Harpel Professor of Capital Formation and Growth at Harvard University's Kennedy School, told ABC News.

Frankel cited the numerous times Trump didn’t take the virus seriously “and actively undermined the practices that we need, like avoiding large crowds, masks and so on” as evidence that the president was not taking the crisis seriously as a policy matter.

“You can't leave something like that entirely to the free market, certainly, or to the states,” Frankel said.

Heidi Shierholz, a former chief economist at the Department of Labor and the current senior economist and policy director at the left-leaning Economic Policy Institute think tank in Washington, D.C., told ABC News, "The utter lack of a coherent, effective response to COVID has just done enormous damage to the economy."

The COVID-19 economic downturn has also made racial inequity worse, Shierholz added, and "hurt Black and Brown communities far worse, not just from a health perspective, but also from the perspective of job loss."

Communities of color bore the brunt of essential work during the crisis, risking exposure to the virus.

The unemployment rate for white workers was 6% last month compared to 9.9% for Black workers and 9.3% for Hispanic workers.

Jobs that could be done at home also tended to require higher levels of education and to be higher paying, according to research from the University of Chicago. By failing to effectively control the virus, Trump’s economy favored the wealthy at the expense of lower-paid service workers employed by hotels, restaurants, hairdressers, and other businesses requiring face-to-face contact.

“If it wasn’t for this pandemic, I think the economy would have still been in pretty reasonable shape," Simon Bowmaker, a clinical professor of economics at New York University’s Stern School of Business, told ABC News. “Not great shape, but reasonable shape.”

“He should have for sure handled it better,” he added, but noted to a large extent it was “an external circumstance” outside of Trump’s control.

Tax Cut and Jobs Act, deregulation and national debt

Even before the virus further exacerbated U.S. income inequality, some experts say Trump’s economic policies favored the wealthy -- and left the poor and middle class behind.

His Tax Cuts and Jobs Act in December 2017 provided major tax breaks to corporations and wealthy individuals. The policy, among other things, reduced the corporate income tax rate from 35% to 21%.

Frankel called the policy "beyond ironic" for a president "who campaigned in 2016 on being the champion of the working man or working person and campaigned on 'draining the swamp' in Washington."

Shierholz said this policy "absolutely increased inequality" and the "vast majority of the benefits of those tax cuts went to the already very wealthy."

The economists also noted that the policy came at a time when unemployment was relatively low and the economy in good shape.

"That's not the time to be giving away trillions of dollars to the wealthy," Frankel said. "When you have a bad shock like the global financial crisis of 2008-09 or like the coronavirus crisis that we're still going through -- that's the time to increase government spending and expansionary fiscal policy, but you lose the ability to do that if you gave it away."

In response to the coronavirus crisis, Congress rallied quickly in March to put out a $2.2 trillion relief package that Trump signed into law. As the virus continued to rage throughout the summer, however, lawmakers and the White House dragged their feet on further aid for months before passing a second relief package at the end of 2020. Even after Congress green-lit the $900 billion package, Trump delayed signing for nearly a week, demanding larger direct checks to individuals, but also unrelated concessions.

NYU's Bowmaker noted that some "can make the case that the corporate tax rate was a little bit too high" and would welcome the tax cuts.

"You can also make the case that there are a number of regulations within the economy which are a little bit burdensome for certain firms and if you put those two things together, the tax cuts and the deregulation, the removal of red tape, you could say it probably contributed to more robust growth than you might have expected," Bowmaker added of the policies.

He noted though that the spending took a toll on the national debt, something Trump pledged in a 2016 interview he would "get rid" of over a period of eight years through trade policy.

Despite his goal, the debt has ballooned under Trump. The total national debt has skyrocketed by more than $7 trillion during Trump’s tenure.

A ProPublica and Washington Post analysis found that the growth in the annual deficit under Trump ranks as the third-biggest increase, relative to the size of the economy, of any U.S. president. The analysis pointed to Trump’s tax cuts as one of the major culprits contributing to the deficits. To the extent that the budget deficits were not offset by increases in private sector saving, they also increased the trade deficit.

Before the pandemic, in the February 2020 Economic Report of the President, Trump and his economic advisers argued that the tax reform contributed to the economic expansion the nation was seeing at the time -- which was the longest on record before the coronavirus recession hit.

“America’s outdated tax code drove away businesses and investment, but tax reform has brought rates down and made the United States globally competitive again,” the report stated.

The report added that these “pro-growth” policies are ultimately good for workers.

“Tax reform put an end to America’s counterproductive policy of punishing business investments, which means that workers will see even greater benefits once these investments pay off,” it stated.

Trade war 'disaster' with China

Trade policy is where the president wields the most economic power, as Congress has over the years delegated negotiating authority to the president’s office, according to Menzie Chinn, professor of public affairs and economics at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Chinn documented the trade war saga on his macroeconomic policy blog Econbrowser.

Trump exercised this power almost immediately during his first years in office and even went so far as to use national security as a basis for trade barriers with China -- something that no president has done in recent times.

Ultimately, the tit-for-tat trade war that Trump waged with China was lost by the U.S., economists say, and data on trade deficits confirm.

Trump’s dramatic trade war upended decades of policy, and kicked off with failed meetings with Chinese leaders in 2017. After the talks disintegrated, Trump initiated the trade war by imposing tariffs on all imported washing machines and solar panels in early 2018. He then announced 25% tariffs on steel imports and 10% tariffs on aluminum. China retaliated with tariffs of up to 25% on more than 100 U.S. products including soybeans and airplanes. The sporadic, retaliatory trade-off battles waged on for years, and dragged other countries that were trying to remain competitive in as well.

“By the end of his term, the trade deficit will be larger in absolute terms than it was when he came to office,” Chinn told ABC News.

Beyond looking at the trade deficit data, Chinn said the U.S. losing the trade war can be seen "to the extent that the tariffs that he put into place raised prices for goods that we import from the rest of the world, so that consumers face higher prices, American manufacturers who use imported inputs pay higher prices, and then probably produce less as a consequence."

"And to the extent that other countries retaliated, reducing our exports, means that … if I look at other metrics, like employment and prices that consumers face, and just net economic output, the U.S. probably lost [the trade war],” Chinn said.

A 2019 report from Moody’s Analytics estimated that the trade war had cost the U.S. economy some 300,000 jobs. A study from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York published in May 2020 found that the trade war reduced U.S. investment growth by 0.3 percentage points by the end of 2019, and is expected to shave another 1.6 percentage points off investment growth by the end of 2020. Moreover, the study says that U.S. firms lost some $1.7 trillion in stock value as a result of the trade war with China.

Trump’s erratic trade barriers, tariffs and spars with the World Trade Organization also stoked massive amounts of uncertainty, Chinn noted. The U.S. trade policy uncertainty index created by Scott R. Baker of Northwestern University, Nick Bloom of Stanford University, and Steven J. Davis of the University of Chicago reached levels in 2019 that were twice as high as had been seen over the last 35 years. The index measures policy-related economic uncertainty by quantifying news coverage, tax code provisions set to expire in future years and disagreements among economic forecasters. Firms did not know if they could import from China, sell to China, or even import from allies and export to allies. This made it much harder for them to plan and invest.

“If you look at the whole range of international trade policies, it's hard to see what benefit was accomplished,” Chinn said. “On trade policy, it's pretty much a disaster.”

Soaring stock market

Trump took every opportunity while campaigning to tout gains in the stock market as evidence of a booming U.S. economy. On Nov. 24, 2020, Trump even broke his post-election silence to hold a minute-long news conference to tout the Dow Jones Industrial Average trading at the 30,000 mark.

"The stock market’s just broken 30,000. Never been broken, that number, that’s a sacred number," the president said. "I just want to congratulate all the people within the administration that worked so hard."

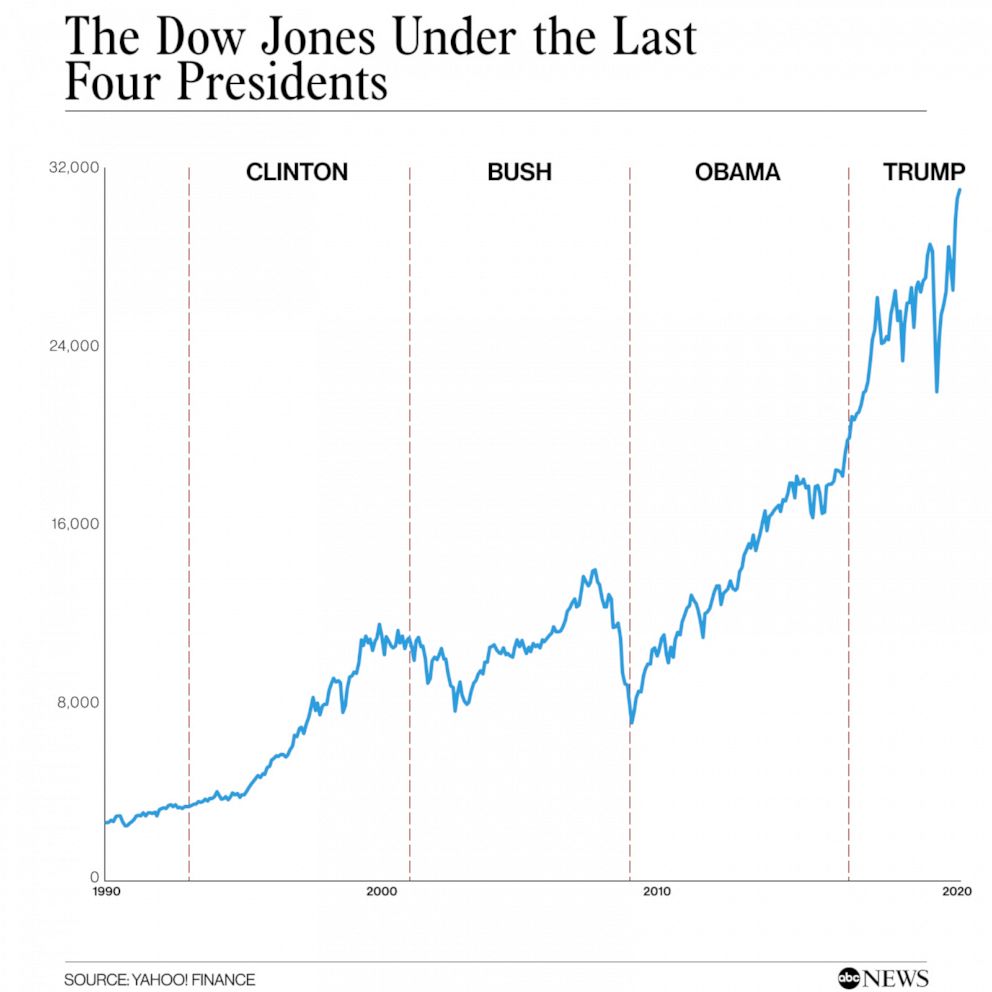

Stock markets have rallied significantly, bouncing back sharply after a March fall to soar to record highs as Trump was in office -- despite the rest of the economy largely receding and suffering.

"The stock market is up phenomenally and the bond market too, so wealthy investors who own most of it benefited," Frankel said of economic wins during Trump's tenure.

Much of the stock market gains, however, economists link to expansionary policy from the Federal Reserve, which is independent of Trump -- and Trump has notably even taken steps to weaken the Fed’s independence. Expansionary policy aims to inject money into the economy, such as the way the Fed slashed interest rates and made it easier to borrow.

The Dow soared by 56% during Trump's presidency. It climbed 148% under Obama, it fell by 26.5% under Bush and climbed 229% under Clinton. Notably, the previous presidents had two terms. At the one term line, the Dow climbed 73.2% under Obama, dropped by 3.7% under Bush and soared 105.8% under Clinton.

"It's not Trump because the stock market is going up even more since Biden won the election," Frankel added.

Chinn noted that “if you lower interest rates by two to three percentage points, that'll give you a stock market boom.”

Another problem with pointing to the stock market as a barometer of the economy is that most of it is owned by the wealthy, and middle- and low-wage workers don't reap the benefits of market gains if they don't own any market shares.

In the third quarter of 2020 the wealthiest 10% of households based on net worth own 88% of all total corporate equities and mutual fund shares, according to Federal Reserve data, with the top 1% owning 53%.

Shierholz said for most working class and even middle class families, stock market gains are "utterly irrelevant."

While Trump didn't create the issue of income inequality in the U.S., his policies will be remembered for creating an economy where the richest prosper while lower-paid families struggle.