Despite Trump's claims, experts say there's no 'magic wand' for a president to declassify documents

Former President Donald Trump isn't the first White House veteran to claim -- in the midst of a criminal probe looking at their handling of government secrets -- that the president can declassify almost anything he wants, whenever he wants, and however he wants.

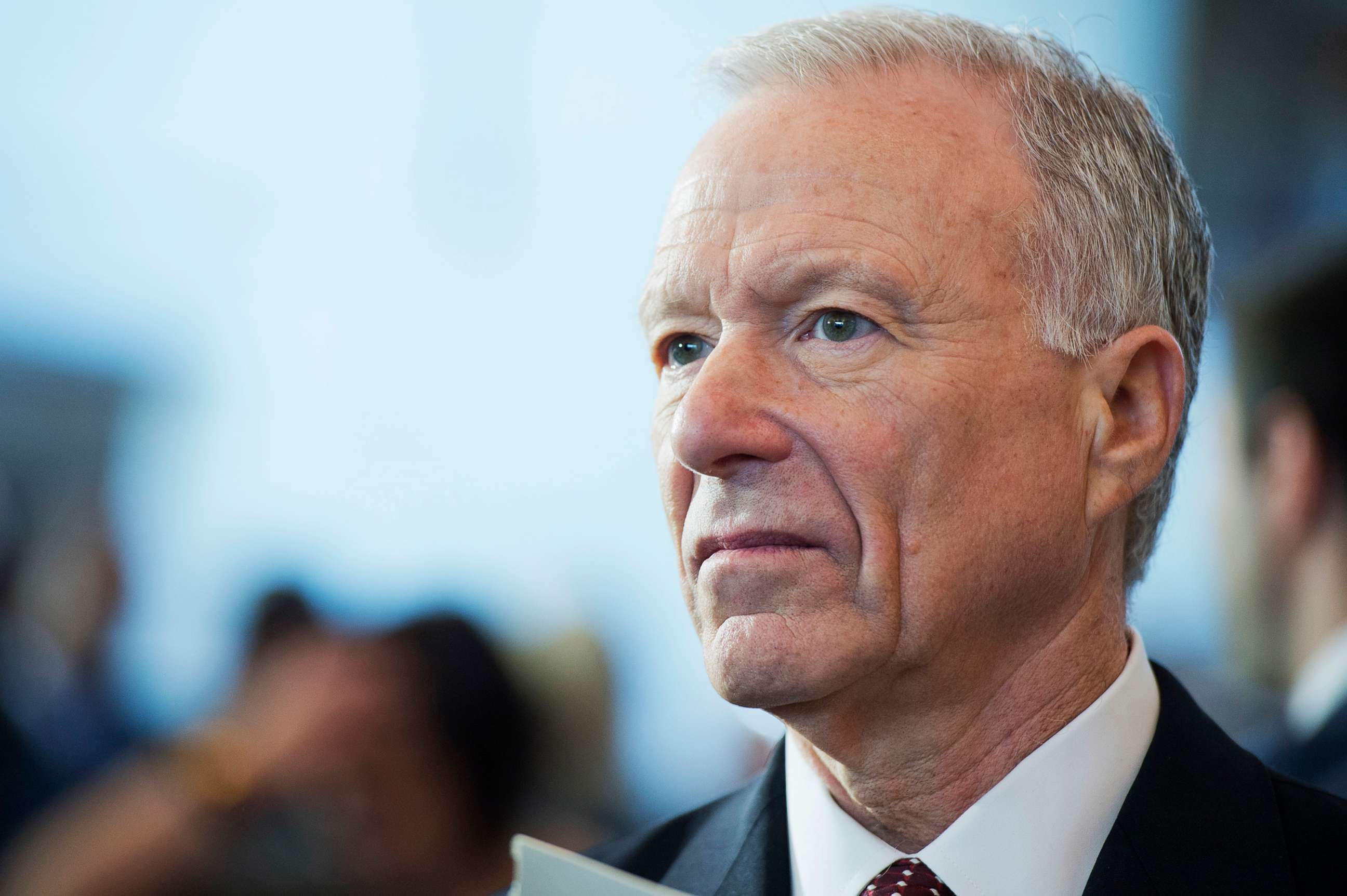

"If the president says to talk about [a] document, it is then a declassified document," the former chief of staff to then-Vice President Dick Cheney, Lewis "Scooter" Libby, told a federal grand jury in 2004. "There's no ... process, according to counsel, that has to be gone through."

At the time, federal investigators were looking into the leak of the identity of a covert CIA operative -- but they were also interested in learning more about how parts of a classified document summarizing Iraq's purported efforts to obtain weapons of mass destruction in Africa had also become public.

Libby admitted to investigators that he "showed" portions of the Iraq document to a New York Times reporter, but he insisted that then-President George W. Bush "had already declassified" those portions by granting permission for Libby to share them with the press.

When transcripts of Libby's testimony were later released, it sparked a public debate over how presidents can -- and should -- wield their declassification authority.

"When the president determines that classified information can be made public ... can that supplant the declassification process?" a reporter asked White House spokesperson Scott McClellan on April 7, 2006. "Is it de facto declassified, by that determination?"

"The president is authorized to declassify information as he chooses," McClellan responded, without offering additional details.

A rigorous review

Nearly two decades later, after FBI agents last week executed a search warrant at Trump's Mar-a-Lago estate and removed several sets of classified documents, there is still little clarification on what a president must do -- if anything -- before a government secret he wants to release is no longer deemed classified.

For most government employees who seek to have information declassified, their requests must go through a rigorous review process that can span the entire U.S. intelligence community, in order to ensure that sources, methods and other national security interests are protected. "[But] there's no formal process that a president is required to follow when declassifying information," Brian Greer, a former CIA attorney who specialized in classification issues, told ABC News.

Nevertheless, Greer noted, "there has to be evidence that a declassification order occurred." And in Trump's case, "the Trump team has yet to produce any credible evidence," he said.

In January, National Archives officials retrieved 15 boxes of records that had been improperly taken to Mar-a-Lago when Trump left the White House last year -- then, two months ago, federal agents visited Mar-a-Lago to retrieve additional materials that they believed Trump had failed to turn over. Shortly after that visit, an attorney for Trump signed a statement saying that all classified documents at Mar-a-Lago had been turned over to federal investigators, sources familiar with the matter told ABC News. But authorities believed Trump continued to possess classified documents, leading to last week's raid.

It's unclear exactly what records were recovered from Trump's residence last week, but court documents filed by the Justice Department indicate that it is investigating, among other things, potential violations of the Espionage Act, which makes it a crime to disclose sensitive national security information that could harm the United States -- even if it's not classified.

After the raid, Trump's team issued a statement to one media outlet claiming that, while still in office, Trump had issued "a standing order that documents removed from the Oval Office and taken to the residence were deemed to be declassified the moment he removed them." On social media, Trump himself insisted that the documents at Mar-a-Lago were "all declassified."

"The president is the ultimate classifier and de-classifier -- but he can't just wave a magic wand, and he can't do it in secret," said Douglas London, a 34-year CIA veteran and author of the "The Recruiter: Spying and the Lost Art of American Intelligence."

"So if [Trump] and his allies are defending his handling of these documents by claiming that they're no longer classified, they need to show the paper trail," London said.

'Nothing short of laughable'

Jeh Johnson, who served as the Defense Department's top lawyer before becoming Homeland Security secretary under the Obama administration, agreed in a piece he published for Lawfare.

"[P]art and parcel of any act of declassification is communicating that act to all others who possess the same information, across all federal agencies," Johnson wrote. "This point holds true regardless of whether the information exists in a document, an email, a power point presentation, and even in a government official's mental awareness. Otherwise, what would be the point of a legitimate declassification?"

Accordingly, Johnson said, the Trump team's claim of a "standing order" that all documents taken to Trump's residence were therefore "declassified" is "nothing short of laughable."

In Libby's case, no information was publicly released confirming that Bush had given Libby permission to share classified information with a reporter -- but at the time, the Bush administration was looking to release the information more broadly, and had initiated an inter-agency review to declassify it.

Amid growing questions over the unfolding war in Iraq, Bush and his allies wanted to bolster their previous claims that Iraq's regime had looked to acquire weapons of mass destruction in Africa. Those claims had come under intense scrutiny at the time after the former ambassador sent to investigate Iraq's alleged efforts, Joe Wilson, publicly disclosed that he found no evidence to support the Bush administration's claims and accused U.S. officials of exaggerating intelligence.

"And so the vice president thought we should get some of these facts out to the press," Libby testified to the grand jury. "But before it could be done, the document [summarizing the intelligence community's conclusions] had to be declassified."

Libby said Vice President Cheney "then undertook to get permission from the president to talk about this to a reporter. He got the permission. Told me to go off and talk to the reporter."

'In the public interest'

Ten days after Libby's meeting with the New York Times reporter, the U.S. government publicly released the document, known as a National Intelligence Estimate.

"What do you say to critics who argue that the president's decision to disclose this information, to effectively declassify it ... [was] a political use of intelligence information?" a reporter asked McClellan, the White House spokesperson, after the document was released.

"It was in the public interest that this information be provided," McClellan insisted.

Libby was ultimately charged -- and convicted -- of something else: lying to the grand jury and federal investigators about his role in leaking the identity of Wilson's wife, Valerie Plame, who was a covert CIA operative. Libby was sentenced to more than two years in federal prison, but his sentence was commuted by Bush in 2007, before Bush left office.

He was then fully pardoned by Trump in 2018.

ABC News' Alex Mallin and Will Steakin contributed to this report.