Trump says he 'saved coal,' but industry employment remains basically stagnant

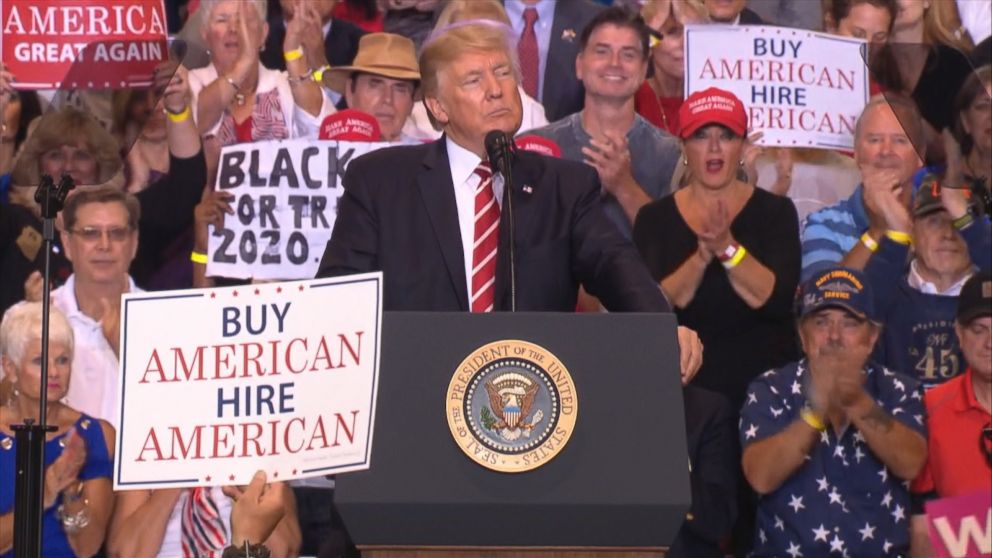

— -- Throughout his campaign, President Donald Trump pledged to revive coal country.

And he insists, a year in to his term, that he has delivered on that promise: "I'm the one that saved coal," he told The New York Times in December.

The president has indeed taken steps to prop up coal mining -- an industry that's been hard hit as new technologies reduce the cost of natural gas and renewable energy.

Last March, flanked by miners, Trump signed an executive order calling for a review of Obama's Clean Power Plan, which aimed to cut greenhouse gas emissions 32% below 2005 levels by 2030.

Because of lawsuits from 27 states, the law was tied up in the courts and had not yet implemented. But the Trump administration -- arguing that the power plan could "potentially burden" the domestic production of energy like coal -- directed the EPA to scrap the plan entirely and propose a replacement.

"My administration is putting an end to the war on coal," the president declared at the E.O. signing ceremony. "Basically, you know what this is? You know what it says, right? You’re going back to work!"

We haven't seen that happen -- at least, not yet.

Fiscal year-to-date, coal production has ticked up, increasing 15 percent compared to the same period last year, from 334.1 million tons to 384.1 million tons, according to the Energy Information Administration.

(Whether that's due to Trump's changes to federal policy or international market demands, like an international need for metallurgical coal used in the production of steel, remains a subject of debate.)

But we haven't seen a corresponding rise in coal jobs, which increased just 1 percent, according to federal data.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, when Trump took office in January, there were 50,000 coal mining jobs in the US; by December, that number had risen to 50,500 -- an increase of just about 500 coal mining jobs.

"We believe it is highly unlikely US coal mining employment will return to its pre-2015 levels, let alone the industry's historical highs," a report from the Columbia University forecast.

So why the disconnect between small increases in coal production and coal jobs?

It comes down to productivity, experts say.

"As processes improve and mining gets more and more advanced, you need less and less people to do the physical work," Tim Boersma, Senior Research Scholar at the Columbia Center on Global Energy Policy, tells ABC. "Though there was an uptick in production, that doesn't necessarily translate into a huge increase in jobs."

These days, "it takes fewer and fewer miners to produce the same amount of coal," agreed Roger Bezdek, president of DC-based energy research consulting firm Management Information Services, who was referred to ABC by the National Coal Council.

Most industry analysts agree that it was automation and competition from other energy sources -- not burdensome regulations -- that were the primary drivers of the decline in coal industry jobs.

Repealing stringent rules on carbon emissions might stave off closures for five to 10 years, says Boersma, but that will merely "buy time for the industry, rather than revive it."

Bezdek, for his part, says the Clean Power Plan repeal "could be significant" but acknowledges that factors beyond the president's control play a role in industry's fate.

The White House declined ABC News' request for comment.

So has the president "saved" coal?

"I think the sense among [Trump] voters is, look, he's trying," Boersma said. But "pretending that we can bring back the past is probably not the right way to go."

"He's taking credit for an awful lot," Bezdek added. "But he has made a difference in terms of morale."